Great frauds in history: Sarah Howe

Sarah Howe defrauded thousands of women through her "Ladies’ Deposit Company" in the late 19th century.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Sarah Howe was born around 1826 in Providence, Rhode Island, in the US, and worked most of her early life as a fortune-teller in Boston. In 1875 she was arrested several times for fraud, usually for taking out multiple loans secured by the same asset, and then refusing to repay them. In 1879 she opened the Ladies' Deposit Company. "Run by women for women," it accepted deposits from unmarried women, and quickly won a following in Boston, attracting $500,000 (around $13m in today's money) in deposits from 1,200 savers, who were attracted by the promise of getting 8% in interest each month.

What was Sarah Howe's scam?

Howe's bank, which she claimed was backed by a Quaker charity, operated as an early Ponzi-style scheme, taking money from depositors with promises of high interest payments, but paying that interest from later depositors rather than, as claimed, from stockmarket investment gains. Unlike Charles Ponzi's original scheme, however, Howe's scam cleverly placed a limit on withdrawals, allowing savers to draw only from accumulated interest payments, and not from their original capital. She justified this rule by saying that it would prevent members from frivolously wasting their money.

What happened next?

Thanks in part to the novelty of seeing a bank being run by a woman, the scheme attracted a lot of interest from the press. As a result, in September 1880 the Boston Advertiser ran a series of articles attacking the scheme, which caused the number of new depositors to dry up and existing savers to start besieging the bank demanding their money back. To begin with Howe starting repaying, handing out $80,000, but this failed to restore confidence. She then went on the run with $50,000 of the bank's money before being arrested and sentenced to three years in jail for fraud.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

Amazingly, given the publicity surrounding the collapse of this scheme, Howe was able to launch another one shortly after her release. This also collapsed, though not before she absconded with $50,000. This time she got off because her victims were too embarrassed to help with the prosecution. Howe's appeal to women is a classic example of affinity fraud the use of social connections and/or shared identity to get victims to hand over cash without asking too many questions. It's never a good idea to invest in the scheme of someone you consider a friend or fellow traveller without doing proper due diligence.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

Could you get cheaper loans under ‘significant’ FCA credit proposals?

Could you get cheaper loans under ‘significant’ FCA credit proposals?The Financial Conduct Authority has launched a consultation which could lead to better access to credit for consumers and increase competition across the market, according to experts.

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

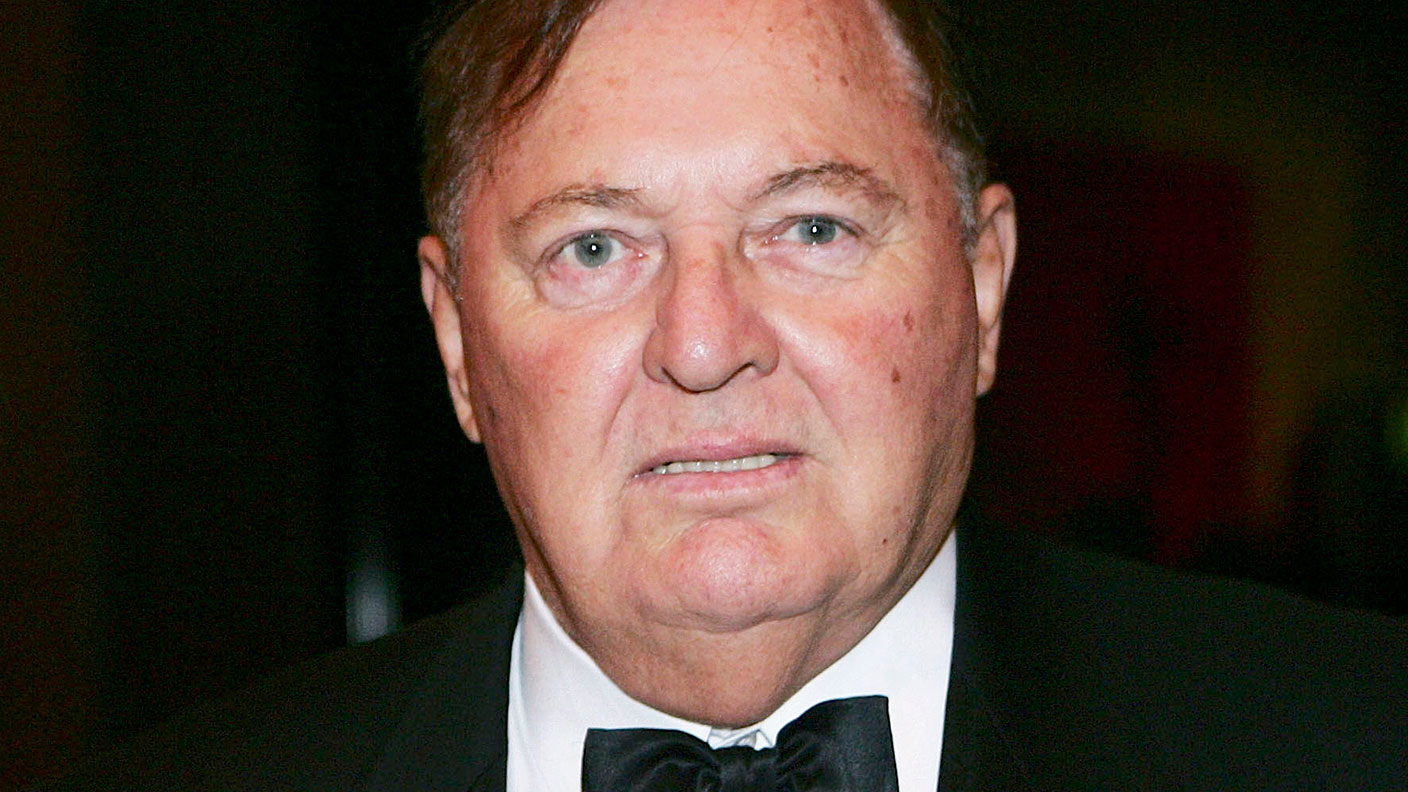

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.