How to profit as the world gets fuller, richer and older

Doomsayers have for centuries warned of the dangers of overpopulation. The good news is that they’ve been wrong so far, says Alice Gråhns – here’s what you should invest in.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Doomsayers have for centuries warned of the dangers of overpopulation. The good news is that they've been wrong so far, says Alice Grhns here's what you should invest in to keep it that way.

Fifty years ago biologist Paul Ehrlich's controversial bestseller The Population Bomb hit the bookshelves. Ehrlich warned that the 1970s would be a decade of mass starvation and ecological disaster, with hundreds of millions of people dying of hunger due to the planet's inability to feed the growing human population.

His sensationalist presentation and drastic policy recommendations won him plenty of readers. In the US, he warned, "we must have population control by compulsion if voluntary methods fail". He continued: "no changes in behaviour or technology can save us unless we can achieve control over the size of the human population". Population growth was a cancer, he said, that "must be cut out".

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Plenty of people took him at his word. The 1968 book arguably helped to inspire such horrors as mass sterilisation programmes in both India and China. But Ehrlich was also wrong. Not so much on population growth itself, but on its consequences.

Like the Reverend Thomas Malthus before him, who made similar forecasts in his 1798 work An Essay on the Principle of Population, Ehrlich underestimated human ingenuity, and in particular the impact of the green revolution (a term also coined, ironically enough, in 1968). This brought with it, amongother things, improved fertilisers, pesticides, herbicides, new farming techniques, mechanisation and genetically modified organisms (GMO). These boosted humanity's ability to produce food from a limited amount of land, and increased agricultural yields significantly.

None of this is to say that we don't face challenges. The current global population of 7.6 billion is expected to reach 8.6 billion in 2030, 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100, according toThe World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, a report published by the UN in July last year. However, in both emerging and developed markets the challenges we face are those that accompany growing prosperity, rather than imminent destruction. And the solutions are all about making better use of our resources, rather than population control.

Baby booms and ageing populations

The real problem we have with population growth today, says economist George Magnus, author of The Age of Aging: How Demographics are Changing the Global Economy and Our World (2008), is that it's not "equally distributed around the world". From 2017 to 2050 (according to the UN report mentioned above), half of the world's population growth will stem from just nine countries: India, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Tanzania, the US, Uganda and Indonesia.

Today, China (with 1.4 billion people) and India (with 1.3 billion) are the most populous countries and account for 19% and 18% of the total global population respectively. Nigeria, which has the fastest-growing population of the ten most densely populated countries in the world, is set to overtake the US as the third-most populous country on the planet before 2050. Africa as a whole is also expected to see its population at least double by 2050.

However, it's a very different story in many other countries. On average, fertility rates have fallen sharply in recent decades as societies have become more affluent. In 1964, the average woman gave birth to 5.068 children, according to the World Bank. By 2016 the global fertility level had decreased to 2.439 children per woman.

Even in Africa, where fertility levels are the highest of any region, total fertility has fallen from 5.1 births per woman in 2000-2005 to 4.7 in 2010-2015. Europe has been an exception to this trend, but hardly a dramatic one total fertility has risen from 1.4 births per woman in 2000-2005 to 1.6 in 2010-2015, which is still below the replacement rate (the level at which the birth rate offsets the death rate, estimated at around 2.1 births per woman). Indeed, between 2010 and 2015, fertility was below the replacement level in 83 countries that comprise 46% of the world's population, according to the UN.

A unique phenomenon in human history

Populations in these countries are still growing (even excluding immigration), but that's due to increased life expectancy rather than having children. As a result, by the end of this decade people aged 65 and older will outnumber children younger than five for the first time in human history, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). Life expectancies worldwide are increasing by roughly one year every five years and will reach an average of 77 by 2050, from 48 in 1950.

As a result, compared with 2017 the number of people aged 60 or over is expected to more than double by 2050 and more than triple by 2100, rising from 962 million globally in 2017 to 2.1 billion in 2050 and 3.1 billion in 2100. This is especially pronounced among rich and advanced economies, says Magnus. But it's also happening in eastern Europe, China, Taiwan and South Korea.

This combination of a growing but ageing population is "a unique phenomenon in human history", says Magnus. "We've never actually experienced weak or falling fertility at the same time as we're seeing rising life expectancy." This will present several new economic problems. For a start, "people don't have enough savings to be idle for the next 20-25 years after they retire", Magnus notes. That's a problem for individuals and one solution will simply be working longer but it's also going to put a lot more pressure on public finances.

If there are fewer young people earning taxable incomes, then the question of how to pay for state pensions becomes much trickier. And that's far from the only future source of pressure on public spending governments have also made plenty of promises to voters about healthcare and residential care. Part of the solution to that may be increased private provision, while automation may also play a part in performing tasks that older populations now struggle to manage.

Rising affluence and increasing consumption

Here's another complication. Not only are populations getting older, but they're also becoming wealthier. Rising affluence is in itself a major factor driving falling fertility rates (due to lower child mortality rates, better education, and better access to contraception, among other things). But as people get better off, they also consume more their diet improves, they may acquire some form of transport, and their whole life becomes more energy-intensive.

It will come as no surprise that (according to Oxfam) the richest 10% of human beings globally produce about half of the world's fossil-fuel emissions, while the poorest half produce 10%. As a result, says Sarah Harper, professor of gerontology at Oxford University and author of How Population Change Will Transform Our World, "the debate is shifting away from overpopulation to population and consumption". As Harper puts it: "it's very clearthat we can sustain large numbers of people, but we have to change our basic consumption patterns".

Countries of the northern hemisphere (academic shorthand for "rich countries") need to reduce their consumption to allow countries of the south (the poorer nations) particularly in Africa "to raise their consumption to levels that are appropriate for the 21st century". In other words, we need to make sure that everyone can get rich without exhausting the planet in the process.

That's not going to be easy asking Americans to consume less so that Africans can consume more is not a practical approach. So again, we need to make more efficient use of the available resources. Specifically, we have to make city life more sustainable. As Magnus points out, income per head correlates closely with greenhouse-gas emissions simply because, as countries get richer, "more people live in buildings in concentrated areas in towns and cities".

The World Bank reckons that, by 2030, 93% of the global middle class will be from developing countries, where they will largely live in cities. And by the time 2040 or 2050 rolls around, the UN estimates that the world's biggest cities will mostly be located in today's developing economies.

If Nigeria's population keeps growing, and urbanisation continues at current rates, then Lagos may become the world's largest metropolis within 60 years, home to between 85 and 100 million people (60 years ago it had a population of fewer than 200,000 people). In an extreme scenario, say demographers Daniel Hoornweg and Kevin Pope at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, by 2100 only 14 of the 101 largest global cities will be located in Europe or the Americas.

We need more food and water

Another obvious implication of a growing, more affluent global population is that it raises demand for finite resources, including the critical ones of food, water and energy. As we've noted already, underestimating humanity's ability to adaptand continue to meet its needs on this front led both Malthus and Ehrlich to mistaken conclusions about our inevitable demise as a species. But clearly, as the population continues to grow, agricultural efficiency needs to continue to improve.

The World Bank estimates that by 2030 demand for food will have risen by 50%. By 2050, the global population is expected to be just 25% larger than it is now. But farmers will need to have boosted food output by 50%-100% just to keep up. The main reason for this is because increased affluence and changing dietary habits mean more demand for animal products, such as dairy, fish and meat, which is a much more resource-intensive way to eat growing feed for animals requires more land, water, and energy than producing food simply by growing and eating plants.

A drying world and renewable energy

It doesn't help that urbanisation, rising affluence and greater consumption levels also result in rising pollution, which in turn is one reason that nearly a third of usable land on the planet is severely degraded, while many water systems have become stressed.

Roughly 1.1 billion people worldwide lack reliable access to water, and a total of 2.7 billion live in areas where water is scarce for at least one month a year. By 2025, two-thirds of the world's population may face water shortages, according to the World Wildlife Fund. This is particularly pertinent to agriculture, which consumes more water than any other industry and wastes much of that through inefficiencies.

Meanwhile, to cut down on global carbon emissions which governments across the world are keen to do we are under pressure to make the shift from using fossil fuels where possible to using low-carbon energy sources (such as solar and wind power, which in turn could be used to charge batteries for electric vehicles, say). If the population keeps growing at this pace, we will need 50% more energy to sustain humanity by 2050. Again, this is skewed by wealth.

The US, for example, has a population of just over 300 million about 5% of the people on Earth yet it consumes 20% of the world's energy and produces 19% of the world's greenhouse gases.

Since Thomas Malthus predicted a disaster in 1798, we've made progress. Hopefully we will continue to prove the doomsaying Reverend and the likes of Ehrlich wrong. But it will require investment and innovation in everything from clean transport and renewable energy to agricultural technology and more efficient water usage. We look at how to profit from these trends in the box below.

The seven stocks to buy now

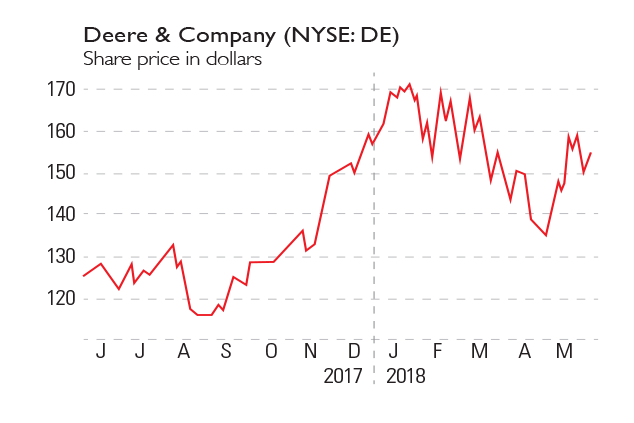

To support a growing and ageing population, the world needs to make more efficient use of its resources. In particular, the pressure on food and water resources will call for innovative technological solutions. Deere & Company (NYSE: DE) might be best known for its tractors, but it is also at the forefront of precision agriculture, which deploys everything from drones to sophisticated sensors to artificial intelligence to help automate farming and boost yields by optimising growing conditions in every inch of a field. The stock trades on a forward price/earnings (p/e) ratio of 16.

Nutrien (Toronto: NTR) is the world's biggest fertiliser company, and was created from the merger of PotashCorp and Agrium, which completed at the tail-end of last year. As populations grow, demand for fertilisers should rise, particularly if prices for food crops also pick up. The merger aims to deliver cost savings of $500m over the next two years.

You can't grow food without water. Solutions to water scarcity a growing problem include desalinating seawater, recycling wastewater for industrial applications, and capturing rainfall. But an even easier win is to patch up leaks and wastage due to faults in existing infrastructure. Aegion Corporation (Nasdaq: AEGN) enables leaky pipes to be fixed without digging up entire roads. The company also extends the life of infrastructure assets such as bridges, buildings and waterfront structures. Full-year revenues hit a record $1.36bn in 2017, up 11% on 2016. It trades on a forward p/e of 19.

Another interesting water-technology play is Xylem (NYSE: XYL), which operates in more than 150 countries. The group makes everything from pumps to smart meters. In the first quarter revenues rose by 14% and Xylem now expects its 2018 full-year revenues to reach at least $5.1bn. The company expects future growth to come from the adoption of smart-meter technology in many countries, and also from infrastructure improvement projects in China and India.

Promises by politicians to slash carbon emissions mean that the shift from fossil fuels to renewables will continue to pick up pace, even as a growing, wealthier population puts ever more pressure on energy supplies. Vestas Wind Systems (Copenhagen: VWS) is the world's largest wind-turbine company. Its shares are down roughly 30% from its peak in the past 12 months and it trades on a p/e of 14. Meanwhile, revenues at US solar-panel maker First Solar (Nasdaq: FSLR) are expected to grow by 22.34% over the next two years as demand for, and use of, solar energy picks up.

The ageing population is putting pressure on healthcare provision. Spire Healthcare (LSE: SPI) is one of the UK's largest private-hospital providers, with around 40 hospitals and 12 clinics. Last year was turbulent for the company, but with the NHS under pressure, particularly as the population ages, the UK's independent healthcare sector should benefit. For Spire a major provider of hip and knee operations in particular the "self-pay" segment of the market is growing rapidly, with individuals (typically in the over-50s bracket) increasingly opting to pay for treatment to avoid lengthy waits. Spire trades on a p/e of 13.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Alice grew up in Stockholm and studied at the University of the Arts London, where she gained a first-class BA in Journalism. She has written for several publications in Stockholm and London, and joined MoneyWeek in 2017.

Alice is now Consumer Editor at The Sun and covers everything from energy bills to Social Security.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debt

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debtCover Story Rising interest rates and soaring inflation will leave many governments with unsustainable debts. Get set for a wave of sovereign defaults, says Jonathan Compton.

-

Why Australia’s luck is set to run out

Why Australia’s luck is set to run outCover Story A low-quality election campaign in Australia has produced a government with no clear strategy. That’s bad news in an increasingly difficult geopolitical environment, says Philip Pilkington

-

Why new technology is the future of the construction industry

Why new technology is the future of the construction industryCover Story The construction industry faces many challenges. New technologies from augmented reality and digitisation to exoskeletons and robotics can help solve them. Matthew Partridge reports.

-

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?Cover Story Universal basic income, the idea that everyone should be paid a liveable income by the state, no strings attached, was once for the birds. Now it seems it’s on the brink of being rolled out, says Stuart Watkins.

-

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolio

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolioCover Story Unlike in 2008, widespread money printing and government spending are pushing up prices. Central banks can’t raise interest rates because the world can’t afford it, says John Stepek. Here’s what happens next

-

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?Cover Story Joe Biden’s latest stimulus package threatens to fuel inflation around the globe. What should investors do?

-

What the race for the White House means for your money

What the race for the White House means for your moneyCover Story American voters are about to decide whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden will take the oath of office on 20 January. Matthew Partridge explains how various election scenarios could affect your portfolio.

-

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?Cover Story Politicians of all stripes increasingly agree with Karl Marx on one point – that monopolies are an inevitable consequence of free-market capitalism, and must be broken up. Are they right? Stuart Watkins isn’t so sure.