Why share buybacks are a red flag

Share buybacks are set to soar – but they differ from dividends in ways that aren’t always good for shareholders.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

US president Donald Trump's corporation tax cuts have already had one very clear impact companies are planning to spend a significant chunk of their windfall on ramping up purchases of their own shares. Last month, notes Justin Fox on Bloomberg, US corporations announced $153.7bn in share buybacks. That's a record for a single month, says research group TrimTabs. JP Morgan reckons that buybacks will total more than $800bn this year, also a record.

Workers might not be too pleased these tax cuts were meant to trickle down into wages and investment, not shareholders' pockets. But for an investor, are buybacks good or bad news?

Share buybacks (more details below) are, in theory, the same as dividends just another way to return money to shareholders. However I prefer dividends for much the same reason as John Lee they keep managers on their toes. A company that issues or raises a dividend will be loathe to cut it, which means it will think twice about whether it can really afford it. Share buybacks, on the other hand, can be ramped up and down with little fuss.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Buybacks, all else being equal, also boost earnings per share (EPS), because the number of shares in issue falls while earnings stay put. That makes it easier for managers to hit their bonus targets meaning there's an incentive to do buybacks for the wrong reason, rather than, say, investing in the longer-term health of the company, as Barry Ritholtz notes on Bloomberg.

However, you can't just dismiss buybacks as always being a red flag. Supporters argue that managers are the ultimate insiders and so should be well informed enough to know to buy when their stock is undervalued. And as Patrick O'Shaughnessy says on his The Investor's Field Guide blog, it's true that companies who make "smart" share buybacks buying shares when their stock is lowly valued usually go on to "significantly outperform" the market. So a strategy that invests in companies doing these sorts of buybacks can be very profitable.

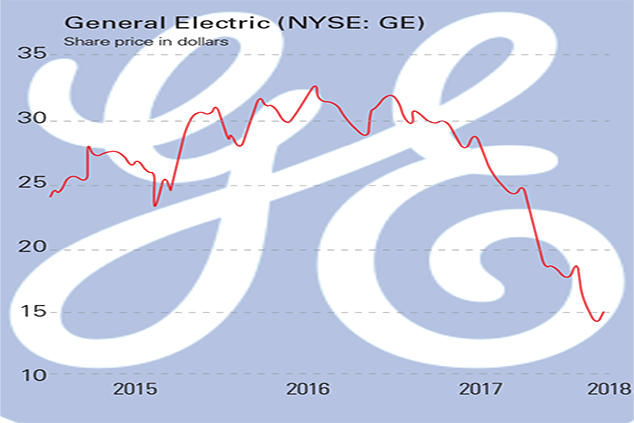

However, "companies that repurchase shares when they are expensive destroy value". The trouble is, that's just what many companies do. As Ritholtz notes, GE has spent more than $50bn on buybacks since 2015. Yet the share price has collapsed over that period (see chart above).

GE is not alone in being dreadful at market timing the last time buybacks peaked was in 2008 (pre-financial crash) while they troughed as markets bottomed out in 2009. Given the US market is now more expensive than at any time since the dotcom bubble, we'd treat any company making buyback announcements right now with greater scepticism than usual.

I wish I knew what a share buyback was, but I'm too embarrassed to ask

There are two main ways for companies to return cash to shareholders. Dividends are one method, and share buybacks where a company purchases its own shares are another. If a company buys back its own shares (assuming it doesn't add others at the same time via the exercise of options, say), it leaves fewer shares circulating, so ongoing shareholders own a bigger (and thus all else being equal more valuable) slice of the firm than they did before.

When a company decides to undertake a share buyback it will typically do so in the open market just like any other investor or via a "tender offer", which involves shareholders submitting a price at which they would be willing to sell. The repurchased shares are either cancelled, or sometimes kept as "Treasury" shares, meaning the company can reissue them if necessary.

Share buybacks are increasingly popular with companies in the US, for example, buybacks took over from dividends as the main route to returning cash to shareholders as far back as 1997, says Justin Fox on Bloomberg. But they are controversial.

William Lazonick of University of Massachusetts Lowell has argued that buybacks are largely driven by management teams trying to maximise their bonuses, and various academic studies back him up one 2016 paper from Ohio State University ("Why does capital no longer flow more to the industries with the best growth opportunities?") concluded that changes in executive incentive schemes in the 1990s have increasingly resulted in cash being diverted from investment in growth towards share buybacks.

Others are less convinced. On Bloomberg, economist Tyler Cowen argues that money spent on buybacks ends up being reinvested elsewhere (by the shareholders who receive the money) so in effect, it's all swings and roundabouts.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’Opinion Bitcoin and gold are both monetary assets and tend to move in opposite directions. Here's why you should hold both