A Star Wars sequel that will not disappoint

Firms providing the next generation of missile-defence systems stand to gain from growing global tensions. Buy in to share the spoils, says John Stepek.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Firms providing the next generation of missile-defence systems stand to gain from growing global tensions. Buy in to share the spoils, says John Stepek.

What can be done about North Korea? While US president Donald Trump tweets insults at "rocket man" Kim Jong-un and the North Korean leader responds in kind by calling Trump a "mentally deranged dotard", all of the juvenile grandstanding rather obscures the fact that there's no easy way for the US to prevent this rogue nation from advancing its nuclear programme (see below).

And it's not just North Korea. Iran is also working on going nuclear. And even if there were a foolproof method for preventing states that don't already have nuclear weapons from ever getting them, there is the ever-present risk of escalating hostilities between powers that do already have them (India and Pakistan, say), or the danger of miscommunication or malfunction causing some horrendous accident involving the world's existing nuclear infrastructure. Living under the dubious protection of "mutually assured destruction" in the Cold War was always somewhat uncomfortable, but at least everyone knew the rules.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

But when it comes to a lone actor such as North Korea, what can the US do? Excepting extreme provocation (such as North Korea actually making good on its threat to attack the US territory of Guam), an invasion of the North is highly unlikely because of the knock-on impact on both China and South Korea. The grim reality is that while everyone outside North Korea recognises that it is hell on earth for those unlucky enough to be born there, neither China nor South Korea are keen to integrate a deeply damaged refugee populace into their own economies think German reunification, only many orders of magnitude more difficult.

Of course, we shouldn't abandon attempts to prevent hostile nations from achieving nuclear status. But given the difficulties involved, and the likelihood that we may find ourselves having to live with a nuclear North Korea, it's also worth investing in some insurance in the form of a defence system. The evolution of strategies to defend against nuclear weapons moved slowly during the Cold War, for both technological and diplomatic reasons.But the US has had a national missile-defence system programme running for many decades now. The North Korean situation might be just the thing to persuade the government to spend a great deal more on it, argues a new report from Deutsche Bank.

Building a nuclear umbrella

The goal of any missile-defence system is to intercept missiles before they hit their target, effectively acting as a shield to protect vulnerable or valuable targets from attack. The goal of a national defence system in particular is to defend against nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). During the Cold War both the US and the Soviet Union made various attempts to develop such a system. The problem, of course, was that if one side got close to developing an effective system, the other would feel forced to bomb them before it went live, or be left at an unacceptable disadvantage in any nuclear war.

As a result, both sides signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) of 1972. This treaty (and later revisions) allowed each country to put in place a very limited missile-defence system (Russia's is still operational around Moscow the US system, based in North Dakota, was shut down after only a few months for budget reasons).

Then in the 1980s Ronald Reagan proposed the Strategic Defence Initiative (nicknamed "Star Wars"). The plan was to create a highly technologically advanced (and unworkable, some believed) network of laser-armed satellites that would protect both the US and the Soviet Union from missile launches, ending the threat of nuclear war altogether, and replacing the doctrine of "mutually assured destruction" with something rather less final. However, the project was repeatedly downgraded due to scepticism about its feasibility and expense, and political support vanished when the Soviet Union collapsed, ending the Cold War (or that phase of it at least, depending on where you think we are today politically). Star Wars was officially shut down in 1993, metamorphosing into the Ballistic Missile Defence Organisation (which focused on protecting specific areas).

In 1999 the US passed the National Missile Defence Act. The point was to create a system "capable of defending the territory of the US against limited ballistic missile attack". As then-US defence secretary William Cohen put it in a speech in 2000, "the threat of missiles from rogue nations is substantial and increasing". Cohen referred to both North Korea and Iran as potential risks, as well as Iraq and Libya. "We project that in the next five to ten years these rogue countries will be able to hold all of Nato at risk with their missile forces." In 2001 the US officially withdrew from the ABM Treaty. This in turn opened the flood gates in terms of budgets the US has been spending heavily on missile defence ever since.

Yet that spending has actually declined by nearly 25% in real terms (adjusted for inflation) over the last decade, according to Myles Walton, Louis Raffetto and Emilee Deutchman of Deutsche Bank. For the last ten years, annual spending has remained flat at around $8bn a year and under the Barack Obama administration it was expected to remain at that level until 2022, as the focus fell more heavily on combating terrorism and troops on the ground.

But now, "Iran and North Korea are cementing a strong validation of the requirements that originally established the National Missile Defence Act of 1999", notes Deutsche Bank. That should change the budget calculus, particularly as a review of the Ballistic Missile Defence system is due this autumn. "We wouldn't be surprised to see the current $8bn run-rate break to the upside towards $9bn-$10bn."

How to knock out a missile

So what does that mean in practice and what are the implications for investors? The missile-defence sector covers all of the components needed to spot and then deal with ballistic missiles of various ranges. That means you need sensor systems to identify launches and track the hostile missiles as they approach, and you need interceptors (to destroy or neutralise the incoming missiles) and the systems for controlling them. The Deutsche Bank report does a good job of running through all of the different items of hardware involved, and comparing missile sizes, but this isn't a Tom Clancy novel, so we'll try to keep it relatively simple.

There are two broad categories to consider. You have systems designed to engage with short-, medium- and long-range weapons and you have systems designed to disrupt or destroy a missile just after it's been launched (the "boost" phase), midway through its flight ("mid-course"), or just before it hits its target ("terminal"). They're all worth looking at in terms of investment (more details below), but most pertinent to the topic of this story are the systems aimed at destroying long-range weapons.

For example, there's the Ground-Based Midcourse Defence System. This, says Deutsche Bank, is "the only US missile-defence asset solely devoted to defending the US from long-range ballistic missiles in the mid-point of their attack". Cutting through the jargon, the Ground-Based Interceptor (GBI) uses ground-based radar and on-board sensors to spot and track an enemy missile, then ram it with a "kill vehicle". It's not very Star Wars and it's not especially reassuring (in tests, it boasts a hit rate of just over 50%), but by the end of this year there are expected to be 44 in action (there are currently 30).

Son of Star Wars

Of course, it would be better if you could hit a missile when it's in the "boost" phase ie, once it's just taken off. Apart from anything else, it avoids the damage done by detonating a nuclear warhead over your own soil. Already, "the initial detection of launches is generally secured by infrared sensors in space", says Deutsche Bank. A programme to create a much larger constellation of satellite sensors to deliver more accurate tracking was scrapped in 2009, but "we see a potential for resurrection/growth" of this plan.

An even more ambitious option would be to restart funding to various weapon systems that could destroy a missile close to launch. Previous attempts the Kinetic Energy Interceptor, the Space Based Laser and the Airborne Laser were all scrapped and funding redirected. But with missile defence becoming more important to both the US and other countries around the world, these programmes or others very like them are likely to see more and more funding in the coming years. We look at the best ways to invest below.

What are the chances of war?

In July North Korea launched its first intercontinental ballistic missile, capable of reaching the west coast of the US. The country has also conducted six nuclear tests since October 2006. The latest carried out early last month was estimated to have a yield of around 160 kilotons, depending on which source you read (for comparison, the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945 had a yield of about 15 kilotons). North Korea is also believed to have mastered "miniaturisation" in other words, it can make nuclear warheads small and light enough to be mounted on missiles. So we already have a nuclear North Korea, and it certainly doesn't appear keen to stop now.

"Images of missiles are everywhere," says US reporter Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times, who warns that he felt "considerably more tension" on his most recent visit to the country than he has on previous visits. Beyond defence purposes, Pyongyang values nuclear weapons from a pure propaganda perspective. Then there's the added revenue stream that could come from North Korea selling the technology to other countries that we'd rather it didn't. As US government official Paul Selva noted this summer: "There's no evidence that they have engaged in proliferation of their long-range ballistic missile technology, but they have proliferated every other weapons system that they've ever invented."

So what are the chances of war? An uneasy stalemate and limited diplomatic discussions still seem the most likely outcome. But with the US currently run by a distinctly undiplomatic president, and North Korea its usual aggressive, isolated, paranoid self, conditions are not ideal for sensible discussion.

And as Kristof says, while North Korea "is rational and cares about self-preservation a dogfight between a North Korean and an American plane could cause a crisis that escalates". Sanctions can only do so much the leadership demonstrably doesn't have a problem with starving its people and it's also worth remembering that even a conventional war would likely involve terrible casualties, in Seoul in particular. They're all good reasons to suspect that, despite Trump's Twitter rhetoric, the US might find that building effective defences is its most viable response to a nuclear North Korea.

The stocks to watch

The geopolitical order is slowly being reshaped. "Pax Americana" is giving way to a world where China and Russia vie for power, while a weary US tries to extricate itself from various unpopular conflicts that its informal role as global policeman has seen it dragged it into. That's been good news for defence stocks in recent years. However, the sudden escalation of fears over nuclear-missile proliferation alongside a desire by US president Donald Trump to boost spending generally look like they could be good for a very specific set of these stocks.

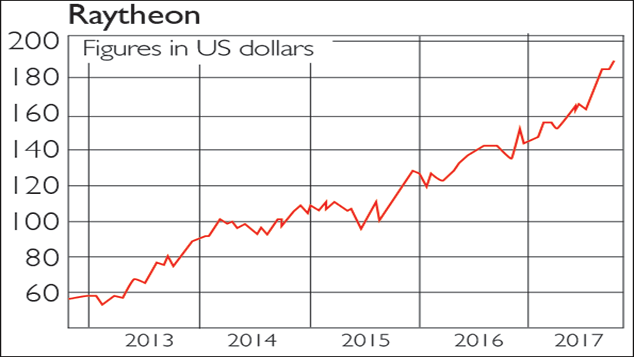

The body in charge of contracts in the US is the Missile Defence Agency (MDA). According to Deutsche Bank, the firms best placed to profit from any spending boost on this front are Raytheon (which generates nearly 40% of its sales from MDA contracts) and Orbital ATK (on 25%), which is now being bought by rival Northrop Grumman for $9.2bn. Raytheon (NYSE: RTN) isn't cheap (on a price/earnings, or p/e, ratio of 25), but it "has the most comprehensive offering in the field of missile defence with both sensors and interceptors" in its portfolio. Deutsche rates it a "buy", with a price target of $210. The dividend yield is 1.7%.

Lockheed Martin (NYSE: LMT) is another tip, on a p/e of 25 and a dividend yield of around 2.5%. Among other things, Lockheed builds the satellites that provide early warning of hostile missile launches. It's already gone quite a way towards Deutsche's price target of $340, so it might be worth putting on your watchlist for a better opportunity.

Northrop Grumman (NYSE: NOC) already works on the Ground-Based Midcourse Defence System (see above) and is gaining more exposure to "rocket launch vehicles, missile technology and satellites" via its acquisition of Orbital, says the FT's Lex column. The stock has come a long way, and hope of further gains "depends as much on heightened belligerence among Washington Republicans as it does on sabre-rattling by North Korea". However, that sounds like a reasonably safe bet to us.

If you'd prefer to invest more broadly in the sector, the iShares US Aerospace & Defense ETF (NYSE: ITA) owns 38 stocks and the top five holdings currently are Boeing (10% of the ETF), United Technologies, Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics and Raytheon.

As for hedging against the worst, the problem with trying to prepare your portfolio for something like war with North Korea is that the asset mix you'd want to own if war broke out is entirely different from what you'd want to own if we end up with a peaceful resolution.As no one can predict the future, putting all your eggs in either basket is a mistake.

Instead, stick with a diversified portfolio. You hope for the best and plan for the worst, and in this case, that means a portion of your portfolio should have exposure to physical gold. It's the best form of financial insurance against this sort of disaster.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debt

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debtCover Story Rising interest rates and soaring inflation will leave many governments with unsustainable debts. Get set for a wave of sovereign defaults, says Jonathan Compton.

-

Why Australia’s luck is set to run out

Why Australia’s luck is set to run outCover Story A low-quality election campaign in Australia has produced a government with no clear strategy. That’s bad news in an increasingly difficult geopolitical environment, says Philip Pilkington

-

Why new technology is the future of the construction industry

Why new technology is the future of the construction industryCover Story The construction industry faces many challenges. New technologies from augmented reality and digitisation to exoskeletons and robotics can help solve them. Matthew Partridge reports.

-

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?Cover Story Universal basic income, the idea that everyone should be paid a liveable income by the state, no strings attached, was once for the birds. Now it seems it’s on the brink of being rolled out, says Stuart Watkins.

-

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolio

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolioCover Story Unlike in 2008, widespread money printing and government spending are pushing up prices. Central banks can’t raise interest rates because the world can’t afford it, says John Stepek. Here’s what happens next

-

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?Cover Story Joe Biden’s latest stimulus package threatens to fuel inflation around the globe. What should investors do?

-

What the race for the White House means for your money

What the race for the White House means for your moneyCover Story American voters are about to decide whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden will take the oath of office on 20 January. Matthew Partridge explains how various election scenarios could affect your portfolio.

-

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?Cover Story Politicians of all stripes increasingly agree with Karl Marx on one point – that monopolies are an inevitable consequence of free-market capitalism, and must be broken up. Are they right? Stuart Watkins isn’t so sure.