The “intelligent fanatics” who inspire greatness

What is it that makes great business leaders stand out from the crowd? Two American small-cap investors think they have found the answer, reports Richard Beddard.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What is it that makes great business leaders stand out from the crowd? Two American small-cap investors think they have found the answer, reports Richard Beddard.

It's the Holy Grail of investment: a way to uncover great companies before they achieve greatness, and the share price gains that go with it. Now two smaller-company investors in the US Sean Iddings and Ian Cassel think they've found the secret. The idea comes from Charlie Munger, who runs US investment company Berkshire Hathaway with the slightly-more-famous Warren Buffett. Buffett and Munger favour companies with sustainable competitive advantages those that add value in a way that cannot be easily copied by rivals. It's these unique advantages known as a company's "moat" that determine how long it will remain a good investment. But what determines the strength of a company's moat? According to Iddings and Cassel, it's all about good leadership or as they put it, intelligent fanaticism.

Here's their definition of an "intelligent fanatic", from the cover of their book, Intelligent Fanatics Project: How Great Leaders Build Sustainable Businesses (2016): "A CEO or management team with large ideas and fanatical drive to build their moat. Willing and able to think and act unconventionally. A learning machine that adapts to constant change. Focused on acquiring the best talent. Able to create a sustainable corporate culture and incentivise their operations for continual progress. Their time horizon is in five- or ten-year increments, not quarterly, and they invest in their businesses accordingly. They own large portions of their business. Regardless of the industry, they are able to create a moat that competitors fear."

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In the book, Iddings and Cassel look at eight leaders one Brazilian, one British and six from the US who founded businesses or turned them around, and grew them over decades into firms that dominated their markets. By studying great leaders from the past, the authors aim to distil characteristics that can be used to identify at an early stage entrepreneurs who can outsmart rivals and build businesses that redefine their industries. Their point is that culture is a firm's one true source of competitive advantage the ultimate moat, if you will and that the most competitive corporate cultures those that empower and motivate staff to delight generations of customers are fostered by intelligent fanatics. Examples in the book include Simon Marks, the son of Marks & Spencer founder Michael Marks, who fought off the challenge of FW Woolworth to establish the superstore concept in the UK. Or Herb Kelleher, who invented a low-cost business model for Southwest Airlines, the tiny Texan outfit he co-founded and ran from 1971 to 2001. It is still America's leading low-cost airline despite having spawned many imitators.

The rewards for correctly identifying a culture shaped by intelligent fanatics can be huge. The estimated shareholder returns attributable to the careers of those studied by Iddings and Cassel range from 16% a year during Marks' 37-year tenure from 1927 to 1964, to the 40% achieved by discount shopping pioneer Sol Price at FedMart and then at Price Club from 1954 to 1993. All eight leaders achieved high returns for at least 30 years, but even over 20 years, the numbers involved compound to mighty totals at 16% a year, £10,000 becomes nearly £200,000; at 40%, it turns into over £8m.

Finding fanatics in the UK

So how can you analyse corporate culture? It's not easy for outsiders to do, except perhaps in hindsight, once the business-school case studies have already been written. However, by reading annual reports, meeting companies as shareholders, and interacting with them as customers, competitors and suppliers, investors can build an impression of the culture within firms. For example, companies often devote more space in communications with shareholders to describing their performance than to explaining how they achieve it. Some are afraid to shed light on their competitive advantages in case their rivals copy them. This can suggest their moat is narrow, and easy to duplicate. Companies with a solid moat ought to be more forthcoming. A strong culture is harder to replicate than a good product, and if it is allied to a profitable business, then it makes sense to boast about it. A company that tells its customers and shareholders why it's so good will attract more of them. It will also deter potential rivals, if they decide that competing head-on would end in failure.

Also, you can take your time. You don't need to invest right at the start of an intelligent fanatic's career to become wealthy riding their coat-tails. Nor, given the returns on offer, do you need to identify many to win. Below, I've looked at some promising candidates for UK investors. Executives at these firms share many of the characteristics identified by the Intelligent Fanatics Project. Better yet, their firms are highly profitable, well financed, and have already grown significantly. In what follows, remember that enterprise value is a measure of the firm's market value (including both debt and equity) and the debt-adjusted price/earnings ratio compares that value to its most recent adjusted profit. But if any of these companies keep earning outsized returns for decades, current valuations will be but historical footnotes.

Philip Meeson, Dart (LSE: DTG)

Enterprise value: £1,075m

Debt-adjusted p/e: 11

Iddings and Cassel found that, with the exception of Marks, all their intelligent fanatics were industry outsiders. Industry dogma, they say, can hold businesses back. When Philip Meeson, executive chairman of logistics and airline group Dart, left the RAF to set up an aerobatics team and run a business importing second-hand Citroen 2CVs, he had plenty of experience of flying, but little of airlines. He eventually bought a business shipping flowers from the Channel Islands, which became Dart in 1991.

Dart is still involved in road freight, but most of its revenue and profit comes from Jet2.com, an airline launched in 2002, and Jet2holidays, a package-tour company launched in 2007. Dart's big idea was to give families in the north of England comfortable holiday flights at convenient times. The young airline doubtless learned much from Kelleher's example just as Southwest honed its business model in Texas before expanding nationwide, Dart has only just extended into southern England Jet2.com flew its first flight from Stansted this year.

Like all the intelligent fanatics, Meeson and his colleagues have developed a unique customer-focused business. It competes with arch-discounters such as Ryanair on service, and with package-tour operators on price. Although it's no longer a small company, it's gearing up for the next phase of expansion with major investment in new aircraft.

Matthew Ingle, Howdens Joinery (LSE: HWDN)

Enterprise value: £2,990m

Debt-adjusted p/e: 15

Howdens Joinery was founded by chief executive Matthew Ingle in 1995 and now has 650 depots across the UK. The firm is not afraid to boast about its competitive advantage it is "proud to be trade-only", with a focus on small builders. It adds value for its customers in several ways: it keeps everything they need in stock; it offers them credit, so they can finish a job before they pay for the materials; and it keeps its prices confidential, so the builder can decide how much of a mark-up to charge.

Howdens exhibits another characteristic of the intelligent-fanatics model: the clever use of generous incentives to attract the best staff and help them flourish. At Howdens, depot managers receive a share of the depot profit, which, the company says, can be "life changing". It also gives managers the autonomy they need to earn their bonuses. Shareholders may rightly wonder how many more depots Howdens can open before the UK is saturated. But while that may happen within a decade, it would be premature to write the Howdens team off yet. Experimentation is another characteristic of intelligent fanatics they are never complacent and Howdens has been experimenting with stores in Europe for ten years.

Andy Walters, Quartix (LSE: QTX)

Enterprise value: £180m

Debt-adjusted p/e: 34

Complexity breeds bureaucracy and sclerosis. A good sign that an intelligent fanatic is running a company is a preference for simplicity, say Iddings and Cassel. One reason Southwest Airlines could cut costs so effectively was because it only used one kind of plane, reducing bills for maintenance and pilot training. That brings us to our next company, Quartix. Some of the builders installing Howdens kitchens will have Quartix telematics systems in their white vans. Quartix rents its systems to firms with small fleets of vehicles. These companies don't have big budgets, or sophisticated needs. They just want to know that staff are not moonlighting or idling, and that they are driving safely between jobs.

In 2001, Andy Walters realised that this was a huge market that could be supplied with a generic product. The trick was to keep costs down, and to remove barriers such as up-front installation charges, or multi-year contracts, that deter small firms from using telematics. The company invests heavily in the product and systems, but only if new developments will benefit at least 80% of customers. Walters, who works from a serviced office in Cambridge and pays himself a very modest salary, explains clearly and simply how the company makes money, and disdains the technical jargon used by the industry to label his products. To Walters, they're not telematics systems, they're vehicle trackers. Indeed, Quartix's devices are probably the easiest bit of the company for a rival to copy. What would be far harder to replicate is its direct-marketing database and its frugal ethos.

John Kearon, System1 (LSE: SYS1)

Enterprise value: £100m

Debt-adjusted p/e: 19

You have to be iconoclastic to upend an industry, say Iddings and Cassel, but you risk losing your customers if you run too far ahead of them. The granddaddy of intelligent fanatics, John H Patterson of National Cash Register (founded in 1884), introduced shopping tills to the world. The technology was too much for American saloon keepers to take in one go, so Patterson stayed a short distance ahead, educating customers via a highly trained salesforce as NCR rolled out improvements to the cash registers.

John Kearon, System1's founder and chief executive, has faced and overcome a similar challenge. He believes the market-research industry has been barking up the wrong tree measuring the persuasiveness of marketing doesn't necessarily predict how effective it will be. Instead, building on the work of behavioural scientists, he believes the extent to which brands and advertisements sway our emotions better predicts their power. System1 formerly BrainJuicer pioneered techniques to measure feelings, enabling it to test and validate ground-breaking marketing, including John Lewis's Christmas ads.

At first, System1 found that telling customers they needed to change their whole approach would often cost it business. So the company turned its techniques into straightforward products, allowing customers to experiment with behavioural testing and see the benefits for themselves, before offering to create marketing for them. Kearon thinks in terms of "Olympic" cycles (it's one of the most significant events in the world of marketing), and he wants the business to double in size each cycle. If it does, staff, who share in the profits, will do very handsomely as will the company's shareholders.

Paul Swinney, Tristel (LSE: TSTL)

Enterprise value: £80m

Debt-adjusted p/e: 30

Companies with long histories inevitably face crises along the way. Yet, helped by their controlling stakes, Iddings and Cassel's intelligent fanatics overcame adversity using courage and adaptability. Paul Swinney, founder and chief executive of Tristel, faced a similar test at the end of the last decade. The company started when Swinney spotted a small advertisement in the business section of The Sunday Times. It offered the chance to invest in a portfolio of disinfectants, whose chlorine dioxide chemistry made them as effective as the strongest disinfectants used in hospitals, yet safer for humans to handle. While the proprietary chemistry was not protected by patents, Tristel patented the delivery and audit systems that allowed it to be used safely.

However, towards the end of the 2000s, Tristel was driven out of its most important market supplying disinfectant for machines that cleaned medical endoscopes when the machine manufacturers acquired their own products. Alive to the risk, Tristel had developed wipes that clean simple instruments without requiring an expensive machine. Tristel Wipes are now the standard method of cleaning these instruments in UK hospital departments. The firm, which has also developed disinfectants for hospital surfaces, veterinary practices and laboratories, now has higher revenues and profits than it had when it was dependent on the machines.

The company is now registering and selling products around the world. Since it takes time and money to get approval for a product, the registrations, like the patents and Tristel's chemical and manufacturing know-how, create a wide moat to deter rivals and Swinney's fanatical persistence doesn't hurt either.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Richard Beddard founded an investment club before joining Interactive Investor as an editor at the height of the dotcom boom in 1999. in 2007 he started the Share Sleuth column for Money Observer magazine, which tracks a virtual portfolio of shares selected for the long-term by Richard. His career highlights include interviewing Nobel prize winners, private investors and many, many company executives.

Richard is freelance writer who invests in company shares and funds through his self-invested personal pension. He has worked as a teacher and in educational publishing, and is a governor at University Technology College, Cambridge. He supports the Livingstone Tanzania Trust, a charity supporting education and enterprise in Tanzania.

Richard studied International History and Politics at the University of Leeds, winning the Drummond-Wolff Prize for "distinguished work in the field of international relations".

-

How to navigate the inheritance tax paperwork maze in nine clear steps

How to navigate the inheritance tax paperwork maze in nine clear stepsFamilies who cope best with inheritance tax (IHT) paperwork are those who plan ahead, say experts. We look at all documents you need to gather, regardless of whether you have an IHT bill to pay.

-

Should you get financial advice when organising care for an elderly relative?

Should you get financial advice when organising care for an elderly relative?A tiny proportion of over 45s get help planning elderly relatives’ care – but is financial advice worth the cost?

-

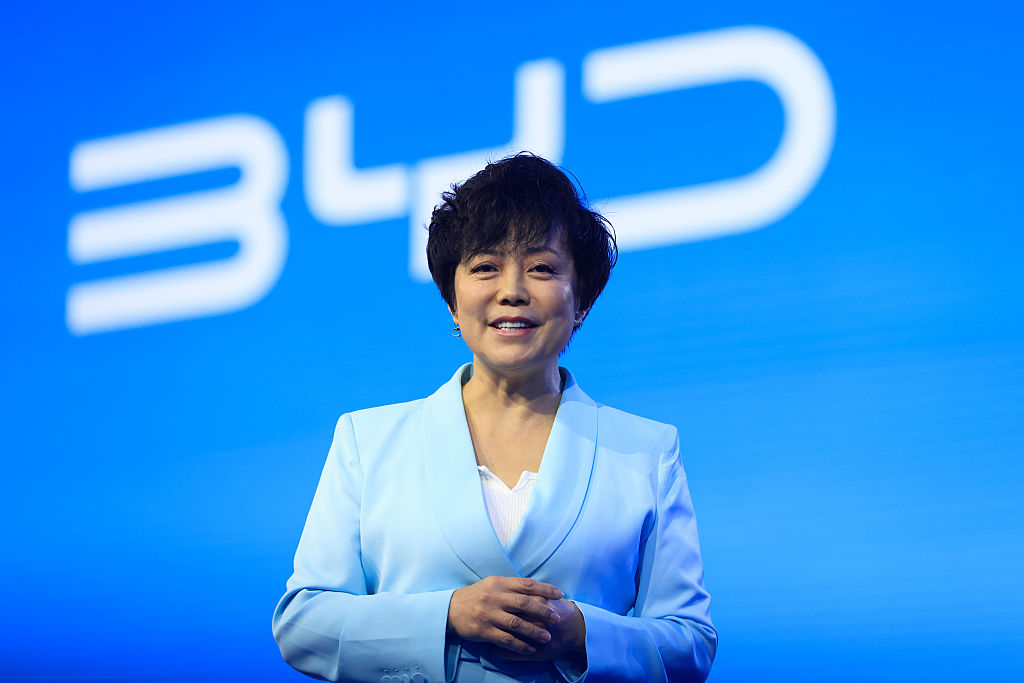

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?Stella Li is the globe-trotting ambassador for Chinese electric-car company BYD, which has grown into a world leader. Can she keep the motor running?

-

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recovery

8 ways to profit from Japan’s recoveryCorporate reform, normalising monetary policy and cheap valuations make Japanese equities a top long-term bet, says Alex Rankine.

-

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growth

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growthCover Story It’s time to invest in Brazil as the economic powerhouse looks set to profit from the two key trends of the next 20 years: the global energy transition and population growth, says James McKeigue.

-

Macron has failed France – but there is still plenty to invest in

Macron has failed France – but there is still plenty to invest inCover Story Emmanuel Macron won a convincing victory in France's presidential election, but he has no clear vision for halting the country’s decline. Frédéric Guirinec looks at the state of France and picks 20 French stocks to buy.

-

The best markets in Asia and how to invest in them

The best markets in Asia and how to invest in themCover Story China and Indonesia should do well over the next year, while India and Vietnam have exceptional long-term prospects. From tech giants to banks, there are plenty of cheap stocks, says Rupert Foster

-

You may not like tobacco stocks, but they treat their investors very well

You may not like tobacco stocks, but they treat their investors very wellAnalysis The tobacco sector may not be ESG-friendly, but it has produced outstanding returns for investors in the past. Rupert Hargreaves looks at whether this can continue – and picks the stock with the best prospects.

-

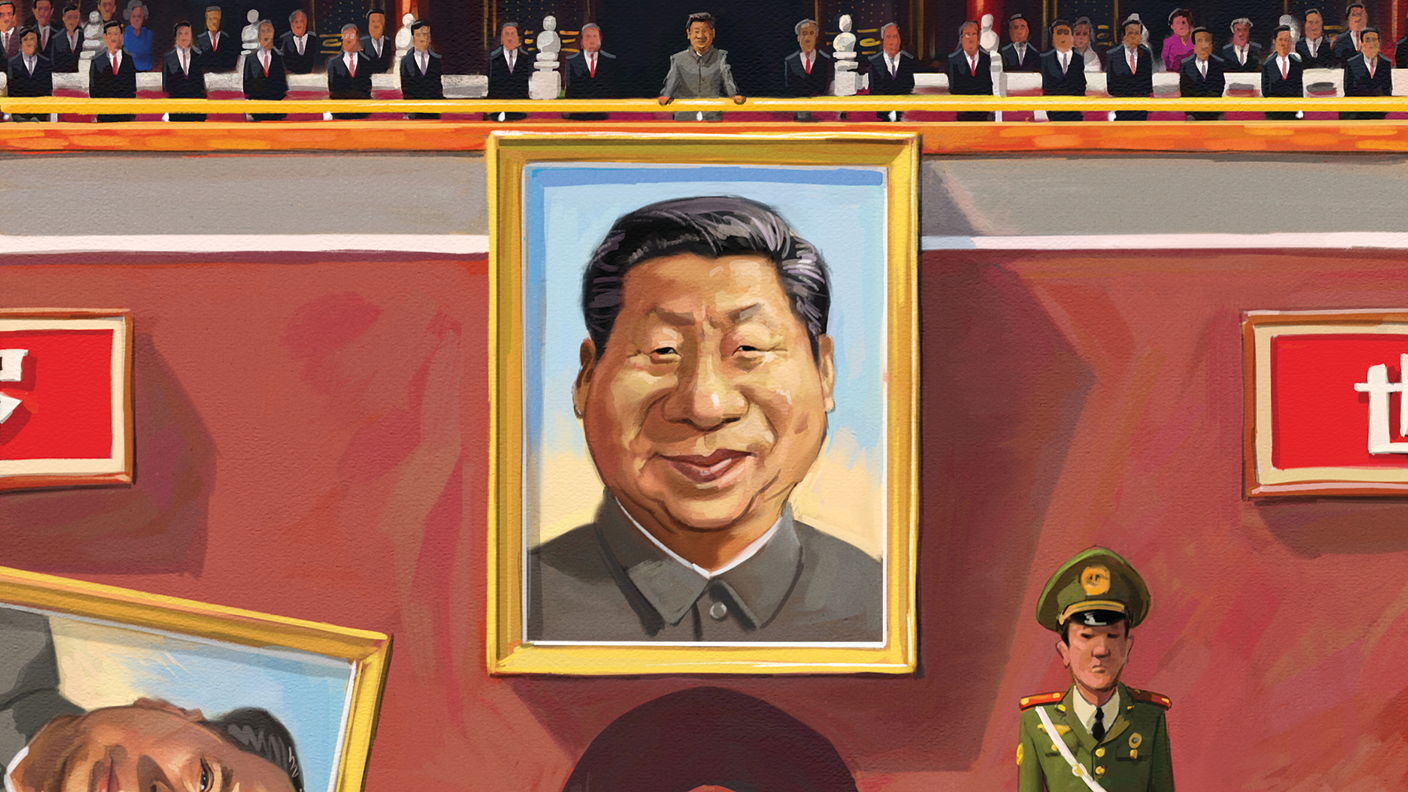

The three key risks for investors in China, and how to tackle them

The three key risks for investors in China, and how to tackle themCover Story Xi Jinping’s vision for the future of China is very different to the past. Stricter social control and the slow struggle to tackle problems in the economy may not be good news for markets, says Cris Sholto Heaton.

-

Japanese stocks offer plenty of promise at the right price

Japanese stocks offer plenty of promise at the right priceCover Story After decades of disappointment, Japan is packed with opportunities for investors, says Alex Rankine.