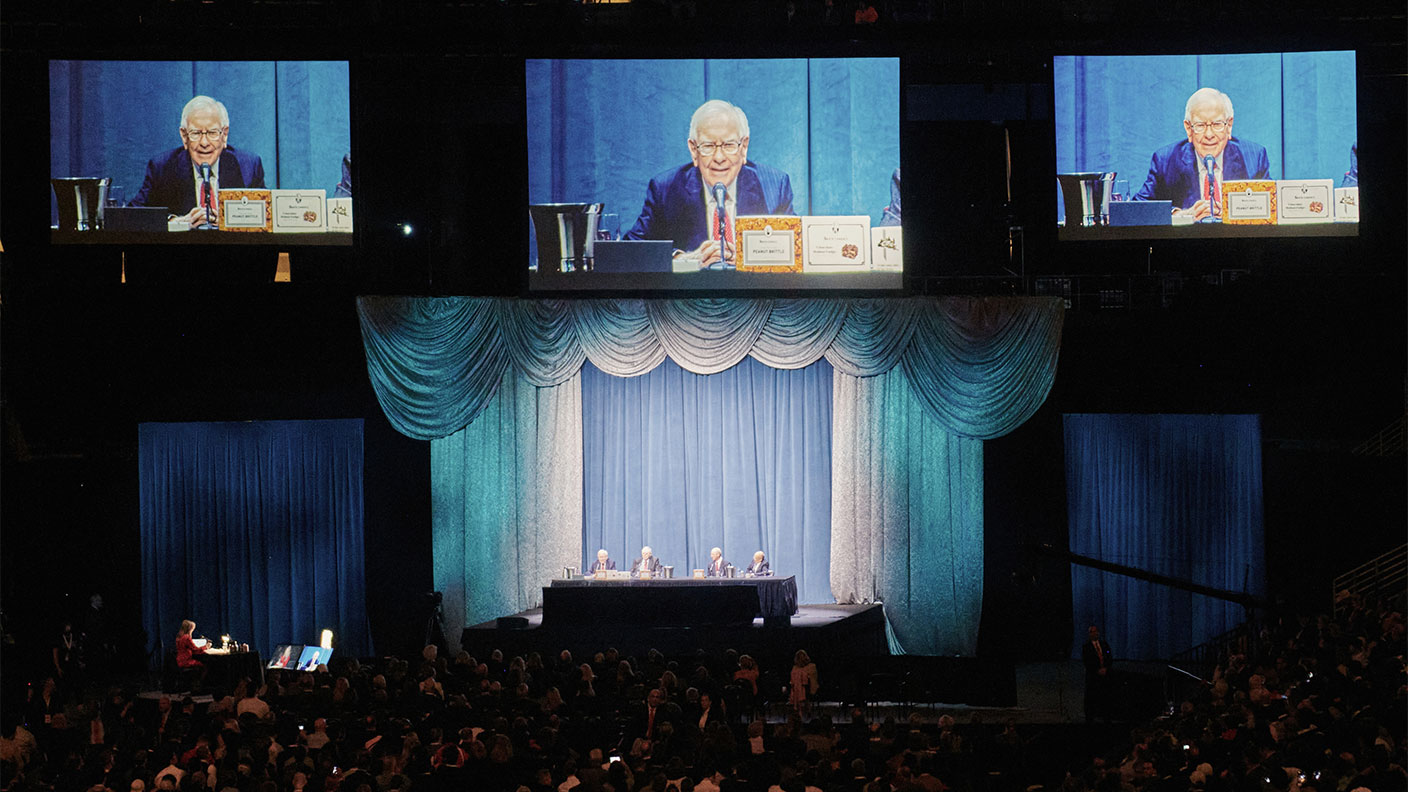

Tips from Warren Buffett’s mentor

Warren Buffett's deep-value approach to investing got him into trouble, says Alex William. Then his mentor, Charlie Munger, gave him some sage advice.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Investment tutorials often promise to teach you how to "invest like Warren Buffett". But you should pay at least as much attention to Buffett's partner, Charlie Munger, who Buffett credits with transforming his investment style. Previously, Buffett was a "deep value" investor, looking for dirt-cheap stocks that still had some value to be eked out of them. This got Buffett into trouble in the 1970s, as he bought into the US textile industry, which only looked cheap because it was failing. Munger persuaded him to pay up for better-quality stocks with higher returns, such as Coca-Cola.

"It's hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it," says Munger. "If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years and you hold it for that 40 years, you're not going to make much different than a 6% return, even if you... buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns 18% on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive-looking price, you'll end up with a fine result."

The most important number

return on capital employed (ROCE)

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The other half of the equation is profit measured as earnings before interest and tax (EBIT). Dividing one by the other gives the ROCE: a firm that generates a $20m profit from capital of $100m has a ROCE of 20%. It's best not to look at the metric for just one year; a one-off bumper profit might distort the figure too high. But a company with consistently high ROCE has a strong chance of consistent growth.

The ROCE figure contains a mountain of information. A business with hefty debts, such as National Grid, employs a lot of capital in its business model, so the ROCE is almost always low. The same goes for a business with low margins, such as Tesco. But most importantly, ROCE tells you how much a company needs to invest to generate its profit. The trouble with capital-hungry industries, such as banks and utilities, is that they require huge investment to grow meaningfully. Even when it has turned a profit, water group Severn Trent has rarely achieved a ROCE above 10%.

As such, even a relatively large investment in its asset base will only generate a modest rise in profit. By comparison, companies in nimbler sectors, such as advertising groups or budget retailers, requirerelatively little fresh investment to keep growing. Budget retailer Poundland had a 49% ROCE last year, reflecting how little it spends on opening new shops, versus the margins it generates. Metal-bashing manufacturers, such as Weir or BAE Systems, usually sit somewhere in between.

Hunting down knock-out companies

Consumer-goods stocks such as Unilever and Nestl have less stellar returns, but trump other sectors on consistency, explaining why they are seen as such stalwarts. Next week, I'll be looking at four British manufacturing stocks with consistently high ROCE that have been sold off hard in the recent turmoil.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Why we need a little patience

Why we need a little patienceAdvertisement Feature In volatile markets it’s easy to get spooked and sell your investments. But that could cost you many thousands of pounds. A patient approach can be much more rewarding.

-

The dangers of derivatives as the “Goldilocks era” ends

The dangers of derivatives as the “Goldilocks era” endsEditor's letter This is no longer a benign environment for investors, says Andrew Van Sickle. But – as the recent pension-fund derivatives blow-up shows – not everybody seems to have grasped that.

-

How Warren Buffett built his fortune

How Warren Buffett built his fortuneAnalysis Warren Buffett is considered by many to be the best investor of all time. We examine how much Buffett is worth and how he made his fortune.

-

A simple lesson from Warren Buffett that even children can learn

A simple lesson from Warren Buffett that even children can learnAnalysis Warren Buffett has an incredible investment record. And at the core of his strategy there is one very simple principle. Rupert Hargreaves explains what it is and how it can help you.

-

Why investors should beware of corporate waffle

Why investors should beware of corporate waffleAdvice When top executives try to retreat behind impenetrable jargon, investors should be very sceptical, says John Stepek.

-

A lesson for value investors from investor Howard Marks

A lesson for value investors from investor Howard MarksAdvice Value investors need to open their minds, says US investor Howard Marks. But why is he saying it now?

-

Why investment forecasting is futile

Opinion Every year events prove that forecasting is futile and 2020 was no exception, says Bill Miller, chairman and chief investment officer of Miller Value Partners.

-

What is value investing?

What is value investing?Value investing covers a broad range of bases, but the approach hinges on identifying companies that are worth more than their price suggests.