Are markets right to be so laid-back over Greece?

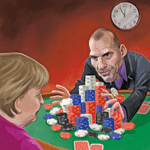

Investors have taken the latest episode in the Greek debt crisis all in their stride. Should they be more worried, asks John Stepek.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Back in 2012 the last time we had a Greece-related crisis in Europe the papers were filled with pictures of burning euros and "Acropolis Now" headlines. Markets dived and midnight crisis talk followed midnight crisis talk until the situation was resolved (albeit temporarily).

Today, even as Greece and the rest of the eurozone go head-to-head once again, markets are positively laid-back. The risks associated with a Grexit have certainly fallen. Banks have cut their exposure to Greece and the European Central Bank (ECB) has pushed through quantitative easing (QE), a major safety net.

But on the flipside, the notion that a Grexit can be managed makes it all the more likely. It gives each side plenty of room to indulge in brinkmanship and play to their respective electorates and potentially reach a point of no return.So are markets right to be so calm?

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The big issue

Greece needs a short-term deal to stop it from running out of money. Formally, 28 February is deadline day the current €240bn rescue package expires then. Informally, it boils down to when the plug is pulled on Greek banks (which still rely on short-term emergency lending from the ECB to keep running), and the Greek government itself runs out of money to pay its creditors which would happen pretty quickly.

At that point, Greece would have no choice but to start printing its own currency (presumably drachma) and default on at least some of its debt (see below).

Both sides have said they want to discuss an extension. But they disagree on the terms. Greece wants a "bridging loan" that allows it to break with the current programme and the reforms it involves. The rest of Europe wants it to commit to extending the current programme.

This may sound like semantics, but it's a big deal. Europe doesn't want to give an inch if it does, it will boost the popularity of anti-austerity parties in other countries, and lead to more requests for special treatment further down the line. But the ruling Greek Syriza party was elected on a promise it would gain concessions from Europe. So it might seem like wordplay, but politically it matters. And if they can't reach a deal, it could be game over.

What would happen?

In the very short run, as Kevin Ferriter of Capital Economics notes, "it is hard to see how the initial reaction at least would be anything other than positive for safe-haven assets and negative for others". That means you could expect demand for US Treasuries (government debt) to rise (and yields to fall).

It might also be helpful for gold (which is why you should hang on to it as portfolio insurance). However, the euro itself may not weaken much further a Greece-free eurozone may be seen as stronger in the longer run.

While unpleasant, most argue that this wouldn't be "Lehman Brothers" part two. The ECB is ready to buy the bonds of any other eurozone countries who fall prey to a market panic, and banks are less exposed to Greece than before. But as Dario Perkins of Lombard Street Research notes: "Nobody really knows what will happen. The ECB's firewalls are untested."

And the biggest problem with allowing Greece to leave the euro is that it breaks "irrevocability" the idea that once you're in the euro, you can't leave.

This is a problem because a Grexit might unnerve savers in other vulnerable countries. "Would Portuguese or Spanish deposit holders keep their euros at home, or would they send them to other, safer' euro countries?" Even if this doesn't happen in the short term, it could easily become an issue in a future crisis.

That said, we're relatively relaxed about the outcome in the short term and would use any weakness caused by Grexit to top up on other good-value eurozone stockmarkets, such as Italy. But in the longer run, even if Grexit is avoided, it's hard to see a solution that deals with this issue over-indebtedness once and for all. Wealth manager Tim Price gives his view here on the longer-term outlook for wider markets.

What happens after Grexit?

What would happen to Greece itself if it leaves the eurozone? Jonathan Loynes and Jennifer McKeown of Capital Economics have outlined one way the process could happen. Firstly, capital controls would need to be imposed and Greek banks closed temporarily, to stop money flooding out of the country. Then a new currency would need to be introduced.

At first this would be "at parity with the euro and all deposits, wage agreements, prices and contracts would be valued on that basis". But it would have to float freely before long, and "would need to drop by as much as 40% in order to restore Greece's competitiveness against the rest of the eurozone".

Inflation driven by drachma-based quantitative easing would be a major risk, although the "vast amount of spare capacity" in the Greek economy might prevent this. A default on at least some of Greece's debt would be an inherent part of any Grexit while this sounds extreme, much of it is now held by public-sector entities, like the ECB.

That would mean tricky talks, but "if Greece avoids defaulting on privately held debt, that may well facilitate an earlier and easier return to market financing". In all, it would be painful but in the long run, by boosting competitiveness, it may "end up as a favourable economic development for both Greece and the rest of the eurozone".

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debt

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debtCover Story Rising interest rates and soaring inflation will leave many governments with unsustainable debts. Get set for a wave of sovereign defaults, says Jonathan Compton.

-

Why Australia’s luck is set to run out

Why Australia’s luck is set to run outCover Story A low-quality election campaign in Australia has produced a government with no clear strategy. That’s bad news in an increasingly difficult geopolitical environment, says Philip Pilkington

-

Why new technology is the future of the construction industry

Why new technology is the future of the construction industryCover Story The construction industry faces many challenges. New technologies from augmented reality and digitisation to exoskeletons and robotics can help solve them. Matthew Partridge reports.

-

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?Cover Story Universal basic income, the idea that everyone should be paid a liveable income by the state, no strings attached, was once for the birds. Now it seems it’s on the brink of being rolled out, says Stuart Watkins.

-

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolio

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolioCover Story Unlike in 2008, widespread money printing and government spending are pushing up prices. Central banks can’t raise interest rates because the world can’t afford it, says John Stepek. Here’s what happens next

-

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?Cover Story Joe Biden’s latest stimulus package threatens to fuel inflation around the globe. What should investors do?

-

What the race for the White House means for your money

What the race for the White House means for your moneyCover Story American voters are about to decide whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden will take the oath of office on 20 January. Matthew Partridge explains how various election scenarios could affect your portfolio.

-

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?Cover Story Politicians of all stripes increasingly agree with Karl Marx on one point – that monopolies are an inevitable consequence of free-market capitalism, and must be broken up. Are they right? Stuart Watkins isn’t so sure.