Is China really facing a property bubble?

Plenty of pundits are warning that Chinese house prices are in bubble territory. But China's housing market is a lot more complicated than the UK's, and fears of a bubble may be overblown. Cris Sholto Heaton explains why.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

China is in the middle of a property bubble. At least, that's what the headlines say. Property sales are up 80% year-on-year. Prices in some hotspots have jumped 20%-30% in a few months. Buyers now queue up when prime new developments go on sale.

But the reality is less straightforward. The Chinese property market is very complicated, and I'm not sure anyone is completely confident they understand it. Arguing that Chinese house prices are in a bubble is not as simple as making the case that US house prices were bubbly back in 2005, for example.

So here's my take on the situation, based on the data, personal observations, conversations with those in the market and the best of the research that I've seen. I'm always interested to get emails from readers working in the areas that I write about, but on this one I'd be especially keen to hear from anyone else working in this sector who has a view as to what's going on.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The Chinese property market is more complicated than most

First, let's look at the background. Yes, sales of residential property to individuals are up almost 80% year-on-year. But as the chart below shows, this follows a collapse in 2008. That wasn't just the result of the global recession. The government had clamped down on real estate late in 2007 because it was concerned that a bubble was building. As a result of this, China's economy was already slowing significantly before the crisis escalated in September.

Figure 1. National Bureau of Statistics, real estate sales to individuals, year-on-year percentage change

Property prices have seen decent gains in recent months but that came after the market slid last year. The overall index shows a 4% year-on-year gain (see below). Apart from the spike in 2007, the trend in recent years doesn't look excessive.

Figure 2. National Development and Reform Commission, house price index, year-on-year percentage change

Of course, different cities and different types of property have performed very differently. In Shenzhen, prices are up 15% year-on-year after being down 15% as recently as January (see below) and that understates how big the swings have been at many developments.

Figure 3. National Development and Reform Commission, Shenzhen house price index, year-on-year percentage change

Overall, Shenzhen and some other major cities may look a bit frothy, for reasons I'll look at later on. But it's hard to make that case for the country as a whole.

Don't rely on Chinese house-price-to-income measures

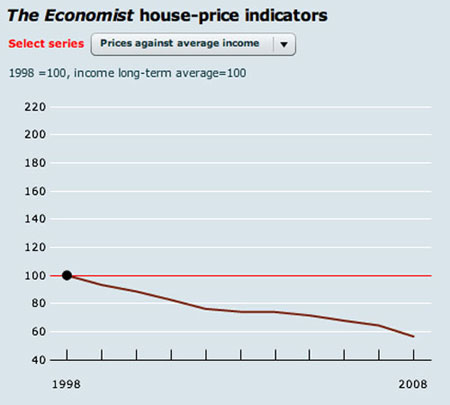

Another statistics that raises eyebrows is the house-price-to-income (HPI) ratio. This compares the price of the average property to the average income, which gives you an idea of how affordable property is.

In most developed markets the ratio tends to be in the region of three to five times. In Asia, five to seven times is typical. In China, it's around nine, and much higher in many major cities.

Surely that's evidence of a bubble? Not necessarily. If we look at the trend in China's HPI ratio, we see something surprising: it's actually been dropping in recent years (see chart below note that this shows the current HPI ratio relative to 1998 and not the absolute value). That suggests Chinese property started off very expensive relative to income, but is now becoming cheaper. So what's going on?

Figure 4. China house price-to-income ratio, relative to 1998

To understand this, we need to look at some of the odd features of the Chinese property market. The first thing to note is that the average person is not paying the average price for the average property.

Most Chinese homeowners live in property which was bought at a huge discount many years ago when the government privatised the housing market. Those who don't, have often upgraded to better housing by selling their initial, subsidised property at a full market price. So this average doesn't reflect the reality of the market (see this piece by consultancy Dragonomics in the FT for more background on this).

So who's buying at full price? To a large extent, the new middle class and the rich. The properties they buy are above the average price, but their salaries are above average too, and have been growing strongly in recent years, hence the fall in the HPI ratio.

On the whole, this is the sector of the market where you read about high demand and big price rises. And this is partly why companies have been paying record-breaking sums for the few remaining undeveloped parcels of prime land in city centres because they believe the high-end part of the market will remain robust, and so they can develop and sell even more exclusive property.

Don't overlook investment demand

It's important to remember that people aren't just buying property to live in they're buying it for investment. And again, there are unusual features about China that make that especially popular. The first is that private property rights are relatively new, so it's not surprising that we've seen rapid growth in real estate as an asset class.

The second is that if you have made some money in business and you're looking to invest it and diversify your wealth, there are limits as to what you can do. Direct investment in many sectors is still explicitly or effectively reserved for the state only. Meanwhile, the domestic A share stock market is a casino. The market for many other assets such as corporate bonds is underdeveloped. And there are restrictions on individuals investing outside China. So the major alternative is real estate.

And this is part of the explanation for developments with very high vacancy rates that some commentators have seen in Chinese cities and cited as examples of overbuilding. Some may be but remember that in Asia, homebuyers often want to take possession of a new, spotless, unused apartment. So if you've bought a place to sell on in the future, you'll probably keep it unoccupied even if you could rent it out, because that will make it worth more when you come to sell.

I don't think this is the best investment choice ever. If you believe that incomes will rise at 8%-10% a year for many years to come, and that increasing urbanisation will boost demand for property (and the 10-year government bond is yielding just 3.2% in comparison), then buying property to keep pristine and sell in a few years' time doesn't seem particularly irrational, not for local investors at least.

Of course, the influx of money into real estate is not just about local mainlanders. Real estate is also popular with foreigners. Sure, they think Chinese property will keep rising, but they also like it as a way to bet on the renminbi being allowed to rise (since few can hold renminbi directly or invest in other renminbi-denominated assets). This is especially relevant in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and of course Shenzhen, the boomtown centre of the special economic zone which borders Hong Kong and is thus a prime candidate for foreign investment.

The government is trying to manage the housing market

Finally, we need to bring government policy into the mix. The central government clearly sees solid real estate prices as important. First, real estate investment is a major part of GDP and is crucial to keeping the recovery going. Second, with a significant share of Chinese households owning their own home (though probably not the 80% sometimes claimed many just have usage rights which can be inherited but not easily sold), weaker prices would be a big blow to sentiment and thus consumption.

At the same time, sky-high prices are also bad politically. While high prices at the top end aren't really a big concern, any sign that the less affluent are being squeezed is bad news. Low-income workers and young people who didn't get a subsidised flat years ago, but are now buying their first home, are reportedly finding it tough to buy in many cities.

For this reason, the government is likely to try to prevent affordability from getting too stretched. At the low end, the state is building more affordable housing. The mid-market will be left to developers (many of which are ultimately state-owned), but the government will probably try to cool the market without crushing it if it thinks prices are overheating.

There's speculation that it will soon remove some of the steps it took to improve sentiment last year, such as lower transaction taxes and home loan rates. This seems to have driven a pick-up in sales in recent weeks after a weaker couple of months, when buyers apparently withdrew as developers raised prices.

Reasons to be optimistic

That slowdown is encouraging: If buyers were being price-sensitive, it's another sign that a widespread bubble isn't emerging. In a genuine bubble, higher prices attract more buyers as excitement builds. But that process tends to be fuelled by easy credit, and China's relatively tight controls on home loans make that harder. Buyers must put down a deposit of 15%. Second-home buyers must pay 40%.

Obviously, these rules are sometimes breached. But generally Chinese homeowners are not overleveraged. Only around a quarter of buyers have home loans and the average loan-to-value ratio is under 50%, according to CLSA. That gives us a second reason to be optimistic: even if prices bubble and the government clamps down too hard and they fall, there shouldn't be a huge population of over-indebted buyers heading into negative equity.

But that doesn't mean that the bank's loan books are in great shape. Many will have heavy exposure to real estate on the construction side. As well as real estate developers who have borrowed to build, many state-owned enterprises in other sectors have ready access to debt, instructions to invest to support the economy, and much more enthusiasm for plunging into real estate investment than expanding elsewhere. So there is still a risk of banks being left with a lot of bad development loans if prices fall.

So, what's the overallconclusion? In my view, there is not a fully-fledged real estate bubble in China. Are there signs of fizz in some segments? Definitely. Could it develop into something worse over the longer run if left unchecked? Very possibly. But is there a widespread credit-fuelled housing bubble set to burst soon and leave the country in the same mess as the US and UK? No. It's a totally different kind of market. China's not perfect by any means, but a collapsing residential property market doesn't look like bringing down the Chinese economy any day soon.

- This article is from MoneyWeek Asia, a FREE weekly email of investment ideas and news every Monday from MoneyWeek magazine, covering the world's fastest-developing and most exciting region. Sign up to MoneyWeek Asia here

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King