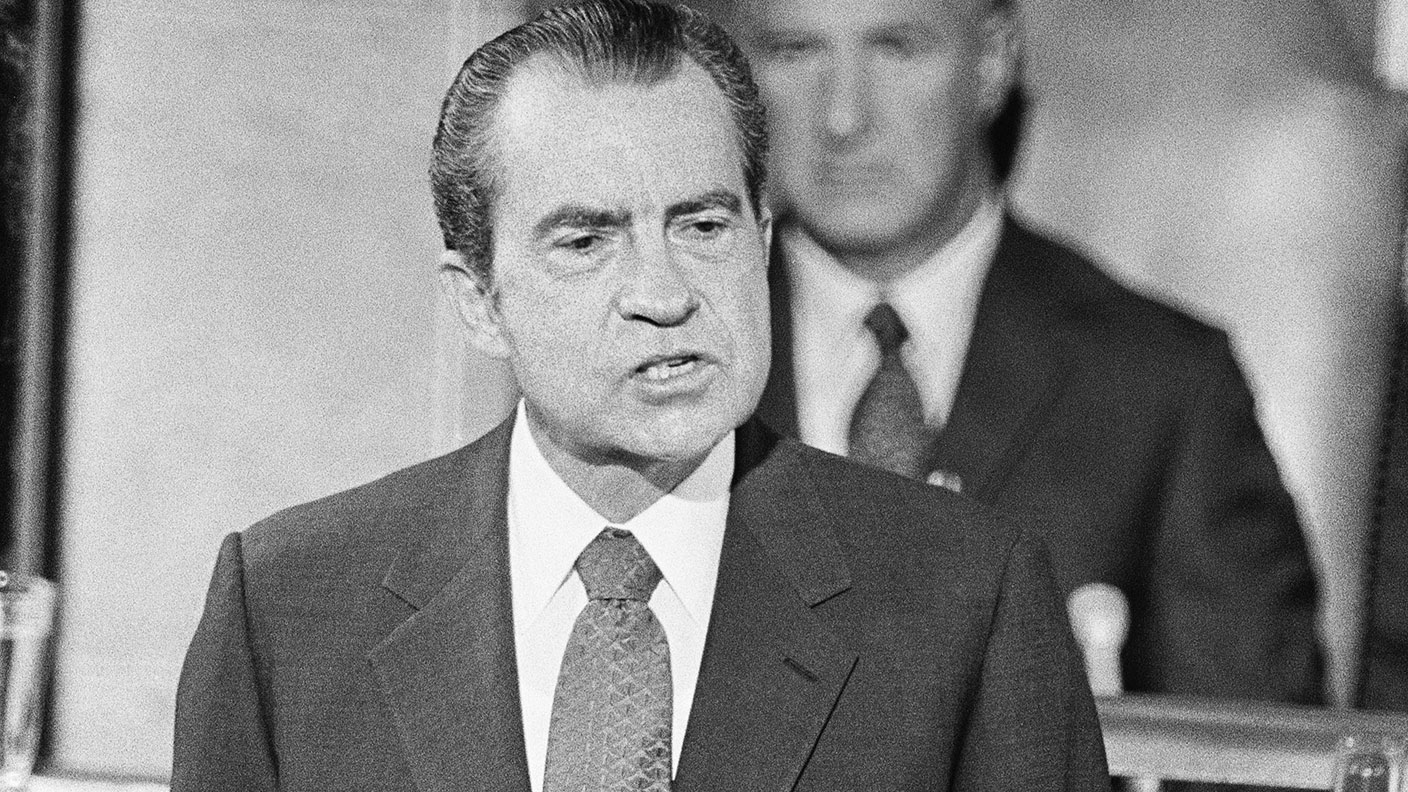

15 August 1971: Nixon ends gold convertibility

On this day in 1971, US President Richard Nixon said America would no longer officially swap dollars for gold, ending 'convertibility' and paving the way for high inflation.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In 1944, under the Bretton Woods agreement, Western leaders created a global monetary system of fixed exchange rates. Currencies were fixed to the US dollar, which was convertible into gold at $35 an ounce.

By backing each dollar with gold, the US implicitly agreed to keep both the money supply and its trade deficit under control.

Initially, it worked. The US ran a trade surplus, helping it to maintain its gold reserves, and kept its debt under control. But during the 1960s, everything changed.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Other countries recovered from post-war dislocation and steamed ahead, while the US ran a trade deficit, and the Vietnam War led to a surge in public spending and the money supply.

As a result, US gold reserves fell to the point where they were vulnerable to a sudden demand for redemptions. Things came to a head in 1971. West Germany decided to leave the gold standard and devalue its currency.

This put US exports at a disadvantage, at a time when unemployment was already high. It also shook confidence in the system, prompting more countries to exchange dollars for gold.

It became clear to the US that without a sudden cut in spending or interest-rate hikes, both of which were politically and economically impossible, the gold reserves would disappear.

So, President Richard Nixon took the drastic step of ending convertibility. To counter inflation, he ordered a 90-day wage and price freeze, and a 10% additional tax in imports, in anticipation that other countries would also devalue.

The move spelled the end of the fixed-exchange-rate system (formally wound up in 1973), and set the scene for the high inflation of the 1970s.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

Pensions vs savings accounts: which is better for building wealth?

Pensions vs savings accounts: which is better for building wealth?Savings accounts with inflation-beating interest rates are a safe place to grow your money, but could you get bigger gains by putting your cash into a pension?

-

31 August 1957: the Federation of Malaya declares independence from the UK

31 August 1957: the Federation of Malaya declares independence from the UKFeatures On this day in 1957, after ten years of preparation, the Federation of Malaya became an independent nation.

-

13 April 1960: the first satellite navigation system is launched

13 April 1960: the first satellite navigation system is launchedFeatures On this day in 1960, Nasa sent the Transit 1B satellite into orbit to provide positioning for the US Navy’s fleet of Polaris ballistic missile submarines.

-

9 April 1838: National Gallery opens in Trafalgar Square

9 April 1838: National Gallery opens in Trafalgar SquareFeatures On this day in 1838, William Wilkins’ new National Gallery building in Trafalgar Square opened to the public.

-

3 March 1962: British Antarctic Territory is created

Features On this day in 1962, Britain formed the British Antarctic Territory administered from the Falkland Islands.

-

10 March 2000: the dotcom bubble peaks

Features Tech mania fanned by the dawning of the internet age inflated the dotcom bubble to maximum extent, on this day in 2000.

-

9 March 1776: Adam Smith publishes 'The Wealth of Nations'

Features On this day in 1776, Adam Smith, the “father of modern economics”, published his hugely influential book The Wealth of Nations.

-

8 March 1817: the New York Stock Exchange is formed

8 March 1817: the New York Stock Exchange is formedFeatures On this day in 1817, a group of brokers moved out of a New York coffee house to form what would become the biggest stock exchange in the world.

-

7 March 1969: Queen Elizabeth II officially opens the Victoria Line

Features On this day in 1969, Queen Elizabeth II took only her second trip on the tube to officially open the underground’s newest line – the Victoria Line.