Do you think like a successful trader?

There are two approaches a trader can take in their thinking, says John C Burford. But only one will ever help you to make profits.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

How does a successful trader think? After all, that must be your goal if you wish to be in their ranks.

Well, it may be easier than you think to achieve this goal. Successful traders are not a dime a dozen, which suggests they must use their minds in a non-conventional way. So, to emulate their success, we need to do the same thing.

In recent posts, I have been quoting from the book Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. This is a book that is highly relevant to traders and I highly recommend you get yourself a copy.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

It may change the way you think about markets and your own approach to trading it certainly has made me consider my own rationality and decision-making process.

So today, I want to talk more about the book and what it teaches us about being successful traders.

Why most traders make poor choices

The takeaway from the book is that every one of us is not always the rational, maximum gain-seeking loss-avoiding agent that forms the foundation of classic economic theory.

Far from it, we are often irrational and emotional with poor choices being the result. In a market context, it is these poor choices that produce the extremes of herding we invariably find at major tops and bottoms.

In the book, Kahneman quotes one of his classic experiments that demonstrates very clearly how poorly we can behave as rational beings.

Let's say you are presented with the following pair of concurrent decisions. Consider each pair, and then make your choices as to the best option overall:

Decision one - choose between:

A) A sure gain of £240B) 25% chance to gain £1,000 and 75% chance to gain nothing

Decision two - choose between:

C) A sure loss of £750D) 75% chance to lose £1,000 and 25% chance to lose nothing

If you are like most of us, you would be attracted to the sure gain of A, and repelled by the sure loss of C. This automatic, emotional reaction is a product of system one. But system one decisions can be poor ones, as I will show.

To evaluate the relative expected values of A and B, upon which you would make a rational choice, you must make a mental effort to think it through. This is a system two operation. The same process occurs when choosing between C and D.

Of course, most people do not want to spend time and energy in thinking things through in a system two process, and they will take the lazy way out and stick to their obvious' system one choices.

Most will choose A over B, and D over C. This is because in the area of average to high probabilities, people tend to be risk-averse with gains and risk-seeking with losses. Were those your choices?

If it's obvious, it's obviously wrong

Only 3% favoured the combination B and C, which, on the face of it, seems a crazy choice. But this combination is actually the most favourable statistically! The expected value of AD is a negative £510, while that of BC is a slightly better negative £500.

That surprising result required the brain to do considerable system two work and that is too much for most people.

What is the lesson for traders? What seemed obvious (A and D is best), was not correct. Herds gather because there is an obvious' story that system one can easily identify with, such as house prices always go up'.

This confirms Joe Granville's maxim (which I love quoting at various times): "When it seems obvious to most people, it is obviously wrong".

Because we know that herding in markets eventually produces the wrong' answer (trends change when the herd gets too big), to answer the question which combination is best, all I need to know was how many respondents chose B and C. And that was 73%. The herd used their system one mind and avoided the hard work of the system two part.

Without doing the harder statistical system two work myself, the large herd in the AD camp told me that the BC combination was likely correct! It was about three-to-one likely. This is classic contrarian thinking.

Does this remind you of how I read the COT (commitments of traders) data?

The recipe for trading success

In a nutshell, that is precisely the attitude you need to adopt to be a great trader. It is a mental process of saying "If..., then...". Using your trading methods of analysis, propose a course for the market (if), and draw conclusions (then).

A good trader does not necessarily want the market to prove them right in their views so that they can brag to their friends. They want to discern what the other traders are doing, and if they are a large herd, look to trade against them.

But with shares, there is one other important herding factor to put in the mix: career risk for money managers.

My colleague John Stepek wrote of this in yesterday's Money Morning. If a manager isn't invested to the hilt in all of the big movers, he or she runs the grave risk of their funds sliding down the performance tables and them out of a very well-paid job.

This peer pressure is enforced herding, while for individual private investors, herding is largely unconscious.

This is what happens when speculators get too excited

| (Contracts of $100,000 face value) | Row 0 - Cell 1 | Row 0 - Cell 2 | Row 0 - Cell 3 | Open interest: 2,585,200 | ||||

| Commitments | ||||||||

| 402,746 | 430,038 | 37,659 | 1,884,109 | 1,654,286 | 2,324,514 | 2,121,983 | 260,686 | 463,217 |

| Changes from 06/17/14 (Change in open interest: -15,886) | ||||||||

| 37,024 | -21,514 | -1,830 | -32,353 | 8,787 | 2,841 | -14,557 | -18,727 | -1,329 |

| Percent of open in terest for each category of traders | ||||||||

| 15.6 | 16.6 | 1.5 | 72.9 | 64.0 | 89.9 | 82.1 | 10.1 | 17.9 |

| Number of traders in each category (Total traders: 356) | ||||||||

| 50 | 99 | 39 | 126 | 165 | 202 | 277 | Row 8 - Cell 7 | Row 8 - Cell 8 |

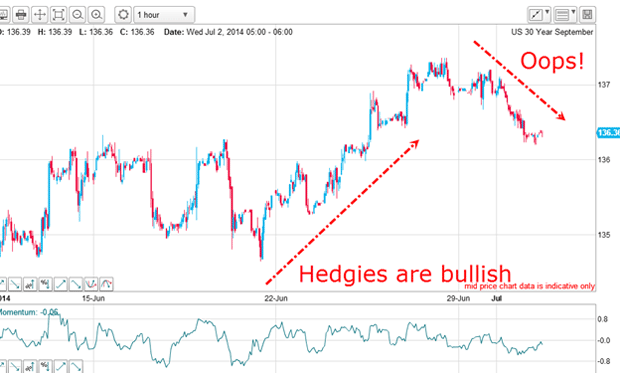

And here is the chart:

This is what typically happens when the speculators get too excited: they are punished for their euphoria.

The lesson? To think like a trader, use your system two analytical mind to examine your knee-jerk, gut-feel system one answers that seem obvious, but may not be.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

John is is a British-born lapsed PhD physicist, who previously worked for Nasa on the Mars exploration team. He is a former commodity trading advisor with the US Commodities Futures Trading Commission, and worked in a boutique futures house in California in the 1980s.

He was a partner in one of the first futures newsletter advisory services, based in Washington DC, specialising in pork bellies and currencies. John is primarily a chart-reading trader, having cut his trading teeth in the days before PCs.

As well as his work in the financial world, he has launched, run and sold several 'real' businesses producing 'real' products.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how