AI in finance: should you take financial advice from ChatGPT?

There are huge opportunities for AI to improve and democratise financial services, particularly financial advice. However, with Brits increasingly trusting generic AI platforms to make financial decisions for them, we investigate the risks

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Artificial intelligence (AI) is making financial advice more widely available. But are some investors taking it too far?

For some time, AI has steadily been making more investment decisions for us. So-called ‘robo-advisers’ offer automated financial advice as well as, in effect, taking investment decisions for their users.

Financial advisers are increasingly-eager adopters of AI technology. The Schroders UK Financial Adviser Pulse Survey 2025 found that 37% of financial advisers have started using AI in their work, nearly double the 21% figure from November 2024.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Rather than selecting their own top stocks, DIY investors are increasingly turning to general-purpose AI chatbots to pick stocks for them, new research reveals.

The study from personal finance comparison site Finder asked 2,000 Brits about their investing habits and found that 16% have used AI tools like ChatGPT or Gemini for stock picks or other investing advice, with 15% admitting to having asked such tools for advice on cryptocurrencies.

Younger people are especially likely to trust AI with their investment decisions: 28% of Gen Z respondents and 34% of millennials had already taken investment advice from AI tools.

“Although investing is more accessible than ever – and an area more people should be exploring – it is slightly alarming to see that one in six Brits are turning to US-built LLMs designed to serve the masses and not provide tailored advice,” said George Sweeney, personal finance and investing expert at Finder. “AI is influencing millions of Brits looking to build long-term wealth, and providing a level of unqualified investment advice.”

AI in financial services

According to the Bank of England, 75% of financial service firms are already using AI and 10% more plan to adopt it over the next three years.

AI clearly has a big role to play in this field. If we include more traditional forms of AI like machine learning (ML) or natural language processing (NLP) in our definition, then AI has been used in finance for decades.

Generative AI (genAI) is a newer phenomenon, at least as far as everyday usage is concerned. In terms of public awareness it dates back to the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022. This is the kind of AI you’re likely most familiar with; it can generate text, images or videos in response to specific inputs (“prompts”).

“Hallucinations” are an inherent property of genAI models. These models aren’t designed to repeatedly answer questions in an identical fashion, but to generate novel responses to a particular prompt based on the model’s training data.

There is, then, an obvious level of risk when it comes to applying AI to finance. GenAI in particular isn’t well-suited – at least, not as well-suited as many people think – to providing accurate information.

“A useful rule of thumb when using generative AI for ‘high risk’ use cases in financial services: if you need to fully explain and repeat the output, don’t use genAI,” says Emily Prince, head of analytics and chair of the AI working group at London Stock Exchange Group.

It is, however, very good at certain things. Typically, these are lower-risk tasks, like summarising documents or consolidating multiple information sources.

Why would I want an AI financial adviser?

Unfortunately, financial advice isn’t available to everyone.

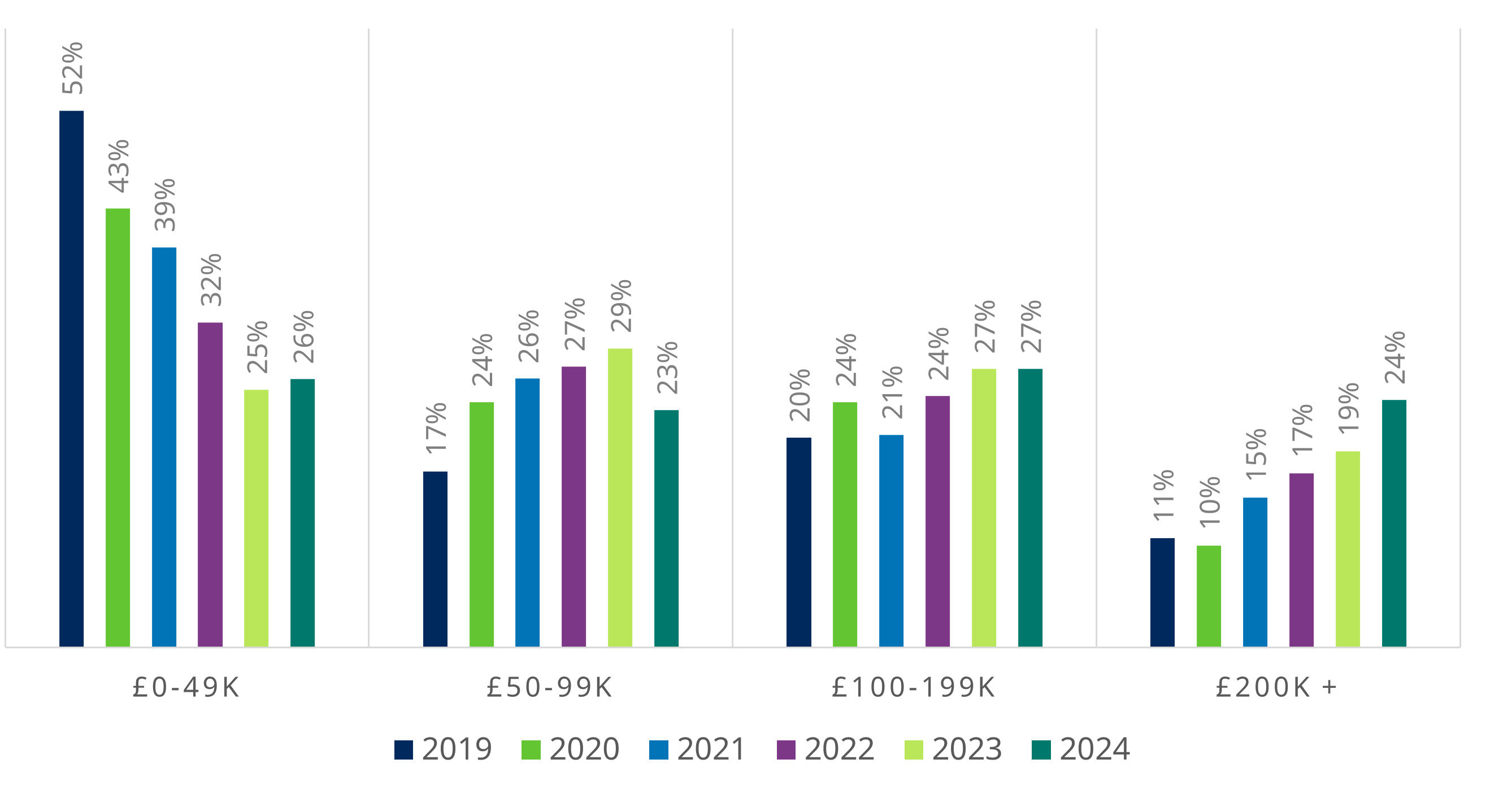

A financial adviser survey from Benchmark Capital, Schroders’ financial advice arm, in 2024 found that 74% of financial advisers will only advise clients with a minimum of £50,000 in assets. More than half (51%) will only advise clients with at least £100,000, and nearly a quarter (24%) will only advise clients with more than £200,000 in assets.

Financial advisers’ minimum asset size for new clients

The average person has just £9,633 in savings, according to research by Raisin UK in May 2025. M&G Wealth Advice’s 2023 Wealth Gap report found that just 11% of adults have paid for financial advice in the last two years. Financial advice remains out of reach for most.

This isn’t financial advisers being stingy. The cost of servicing a client is, on average, £800 per year. If an adviser charges 1.5% of assets, that implies £53,333 in assets just to break even. Given the inputs required, it just isn’t economical for advisers to serve lower-wealth clients – yet these are the people who need financial advice most of all.

How is AI used in financial advice?

The hope is that AI can help to bridge this advice gap by bringing down the cost of providing financial advice.

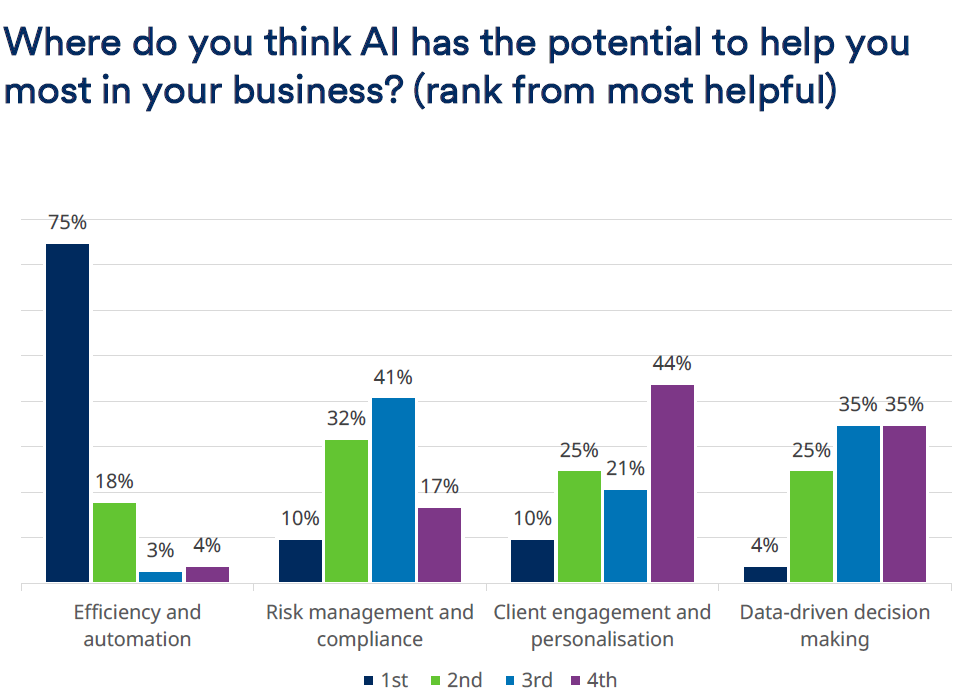

A recent survey by Schroders found 75% of financial advisers said improving efficiency with automation was the most helpful use case for AI in their business.

AI is also being built into external-facing financial products. Many of these are already making decisions for us: according to the Bank of England, 55% of AI use cases in financial services involve a degree of automated decision-making.

One good example is robo-advisers. These offer ready-made portfolios based on risk appetite, as well as a degree of AI-led portfolio management (like automated rebalancing). Some popular providers are InvestEngine, eToro’s Smart Portfolios, IG Smart Portfolios and Moneyfarm.

There are also increasing levels of AI being built into the financial advice service. Octopus Money, for example, integrated solutions from Aveni, an AI developer that creates products specialised for financial services, into its advice offering in March.

How accurate are genAI tools in finance?

If you’re taking financial advice from AI, it’s important to understand exactly how accurate the source that you’re using is.

In general, steer clear of unspecialised generative AI platforms like ChatGPT.

A study from Investing in the Web found that ChatGPT answered one in three questions about finance and investing incorrectly – not something you’d want to happen if you were trusting it with your investments.

Not only do genAI tools often give wrong answers, but they frequently don’t have access to the latest information on things like share price movements.

“ChatGPT search is a welcome application that can save us a lot of time, but it can also misdirect us if we’re not careful while using it,” says Pedro Braz, CEO of Investing in the Web. “Where the subject matter is as serious as personal finances, overuse of AI can have a significant negative impact.”

If you are going to use ChatGPT for financial advice, do so relatively early in the process, says Braz, “to help clarify terms or shed light on a general topic”.

“Using it to ask more personalised questions is where the risk of miscommunication comes into play,” he says, adding that it is also a good idea to ask your generative AI tool for a list of sources so that you can fact-check its response.

GenAI tools, unlike a real financial adviser, also lack the ability to provide tailored advice, according to Sweeney.

“Ordinary people could run into trouble if they start investing without a clear understanding of their own goals, time horizon, and risk appetite,” he said. “Sadly, ChatGPT can’t decide the answers to these sorts of questions for you.”

While AI can provide sound financial advice, you should only trust this advice if it comes from a bespoke, industry-specific source. Out-of-the-box genAI platforms like ChatGPT may not be accurate enough to be relied upon.

“Don’t take ChatGPT tips as sacrosanct,” said Sweeney. “It’s a useful tool but you must combine it with your own research and compare your options or consult a qualified financial advisor before making any important, long-term decisions with your investments.”

The need to regulate AI-generated financial advice

The ability of genAI to make mistakes means that there are obvious caveats to its use in financial advice. Industry bodies warn that there needs to be regulatory oversight of the technology in order to protect consumers.

“Not all AI is created equal,” says Phil Turnpenny, policy executive at The Investing and Saving Alliance (TISA). “Search engine-based AI tools are increasingly being used as a source of financial advice – often without oversight, transparency, or accountability.

“This has created a wild west situation and poses serious risks, particularly for vulnerable consumers who may be misled by confident-sounding but inaccurate information.”

TISA is campaigning for the Financial Conduct Authority and His Majesty’s Treasury to bring genAI search engines within the purview of financial regulation in order to protect consumers.

“Our research shows that properly designed and regulated AI has the power to improve financial access and outcomes – especially for underserved groups,” says Turnpenny. “We must draw a clear line between risky, unregulated tools and those that are built with consumer protection at their core.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Dan is a financial journalist who, prior to joining MoneyWeek, spent five years writing for OPTO, an investment magazine focused on growth and technology stocks, ETFs and thematic investing.

Before becoming a writer, Dan spent six years working in talent acquisition in the tech sector, including for credit scoring start-up ClearScore where he first developed an interest in personal finance.

Dan studied Social Anthropology and Management at Sidney Sussex College and the Judge Business School, Cambridge University. Outside finance, he also enjoys travel writing, and has edited two published travel books.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Big Short investor Michael Burry closes hedge fund Scion Capital

Big Short investor Michael Burry closes hedge fund Scion CapitalProfile Michael Burry rightly bet against the US mortgage market before the 2008 crisis. Now he is worried about the AI boom

-

Can you rely on artificial intelligence for financial advice?

Can you rely on artificial intelligence for financial advice?AI still has plenty to learn when it comes to financial planning, research suggests

-

Rishi Sunak: MoneyWeek Talks

Rishi Sunak: MoneyWeek TalksPodcast On the MoneyWeek Talks podcast, Rishi Sunak tells Kalpana Fitzpatrick that we need better numeracy skills to improve financial literacy and boost the economy.

-

'Gen Z is facing an AI jobs bloodbath'

'Gen Z is facing an AI jobs bloodbath'Opinion It has always been tough to get your first job, but this year, it's proving tougher than ever. AI is to blame, says Matthew Lynn

-

5 AI scams to be aware of

5 AI scams to be aware ofAI scams are revolutionising how fraudsters operate. We explain what to look out for and how to protect yourself