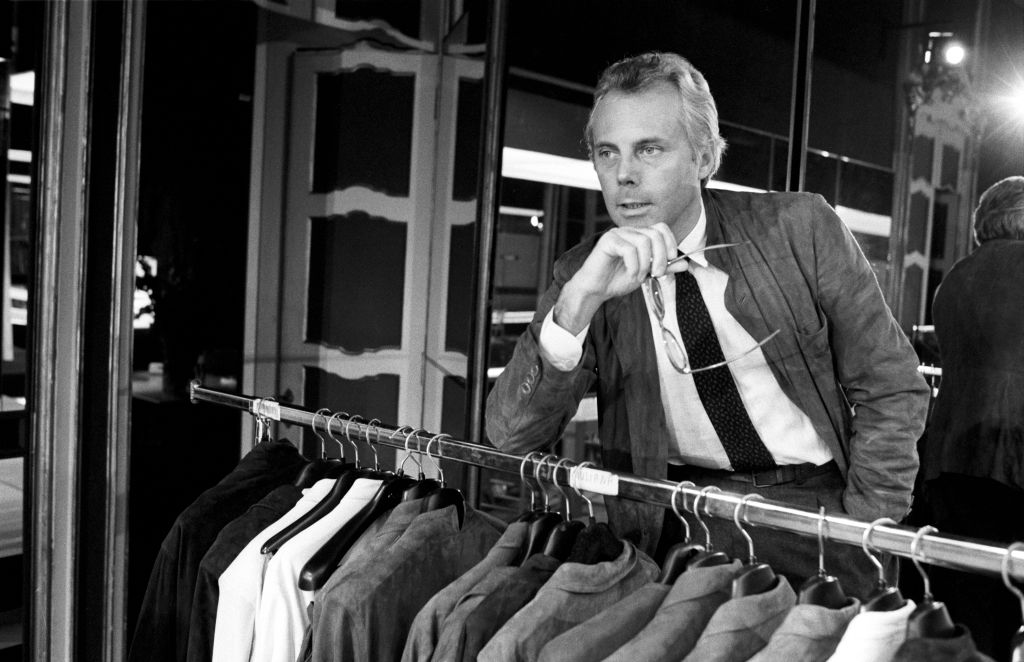

Giorgio Armani: the irreplaceable Il Signore

Giorgio Armani started his fashion business in 1975 with the proceeds from the sale of his car and built it into the world’s largest private luxury brand. Where can it go without him?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

“Life,” Giorgio Armani once observed, “is a movie. And my clothes are the costumes.” It was an attitude that served him well, says Vogue. The legendary “Il Signor”, who has died aged 91, was “unarguably the most successful Italian designer in history” – credited with designing “the uniform of aspiration that both defined the 1980s and shaped the course of fashion beyond it”.

The business he began from scratch in 1975, “funded with the sale of his Volkswagen Beetle”, eventually came to employ 8,000 worldwide and earned him a $12 billion personal fortune. By the time of his death, notes the Financial Times, the fastidiously independent Armani – who called the shots at his company until the very end – had built “the world’s largest private luxury brand”.

Armani “almost single-handedly established Milan as a serious rival to Paris as the world’s fashion capital”, says The Telegraph. A great populariser, he shrugged off the snobberies of haute couture, saying he only wished “to make men and women look better”. Credited with considerable commercial nous, he didn’t object when a profitable industry sprang up in counterfeit Giorgio Armani products. “Actually,” he once said, “I am very glad that people can buy Armani – even if it’s a fake. I like the fact that I’m so popular around the world.”

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Born in Piacenza, south of Milan, in 1934, Armani was the second of three children. He later cited growing up under the fascist Mussolini regime for his dislike of structured uniforms. Accordingly, “when he began to design, he turned his attention first to that emblem of male hierarchy, the suit”. He took a few detours getting there. Armani’s initial ambition was to become a doctor and he studied medicine at the University of Milan for three years before a stint at an army hospital “scotched” the inclination. Turning to photography, he approached Milan’s leading department store, La Rinascente, and “soon found himself working on its window displays”.

A formative stint working on Nino Cerruti’s Hitman label followed. Here, Armani “learned the economics of fashion” and earned the enduring respect of his boss. Cerruti later denied any suggestion that he had “discovered” Armani; he said Armani had “discovered himself”. Nonetheless it was Armani’s boyfriend, Sergio Galeotti, an architectural draughtsman, who persuaded him to form his own company and set up the early deals.

Who will carry Giorgio Armani's legacy forward?

Armani’s fluid tailoring – in his trademark subdued palette – turned heads from the start as the antithesis of both of Savile Row orthodoxy and the hippy philosophy of the 1970s. But his breakthrough came in 1980 when he dressed Richard Gere in the film American Gigolo. Almost overnight, he told The Economist, the label became “a sensation”. In 1983, Armani became the first designer to open an office in LA. Where Hollywood led, suave businessmen followed, and Armani swiftly followed up with a line for working women. When Galeotti died in 1985, Armani became introspective, says The Telegraph, but continued expanding the business – establishing “a pyramid of brands targeting different price levels”. The 1990s were marked by diversification into sunglasses, sportswear and restaurants.

For all his success, he retained “a sense of melancholy” and “a shyness”, says The Telegraph. He was happiest at his home on the remote Sicilian island of Pantelleria and sailing the Mediterranean on his yacht. In his later years, Armani involved various nephews and nieces in the business. Pantaleo Dell’Orco, who heads the men’s style office, has also taken on an increasingly important role. But Armani’s iron grip on the company leaves the question of who will succeed him unanswered. He knew as much himself. “I don’t know how any of us can think any of this is replicable without me.”

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Adventures in Saudi Arabia

Adventures in Saudi ArabiaTravel The kingdom of Saudi Arabia in the Middle East is rich in undiscovered natural beauty. Get there before everybody else does, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Review: Constance Moofushi and Halaveli – respite in the Maldives

Review: Constance Moofushi and Halaveli – respite in the MaldivesTravel The Constance resorts of Moofushi and Halaveli on two idyllic islands in the Maldives offer two wonderful ways to unwind

-

Affordable Art Fair: The art fair for beginners

Affordable Art Fair: The art fair for beginnersChris Carter talks to the Affordable Art Fair’s Hugo Barclay about how to start collecting art, the dos and don’ts, and more

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

Review: Gundari, a luxury hotel in the Greek island of Folegandros

Review: Gundari, a luxury hotel in the Greek island of FolegandrosNicole García Mérida stayed at Gundari, a luxurious hotel on Folegandros, one of the lesser-known islands in the southern Cyclades in Greece

-

Fine-art market sees buyers return

Fine-art market sees buyers returnWealthy bidders returned to the fine-art market last summer, amid rising demand from younger buyers. What does this mean for 2026?