The days of plenty are coming for insurers – it’s time to buy

Between Covid-19 and tropical storms, last year will leave insurance companies with some hefty payouts. But investors shouldn’t be put off. John Chambers explains why the cycle is now turning in favour of insurers.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

London is home to one of the great unsung heroes of the UK economy. The London insurance market is the clear global leader in commercial insurance. Most of the world’s largest companies buy at least one policy in London and over $110bn of premiums are underwritten there each year, more than twice that of its nearest rival, Bermuda. Insurance is responsible for a quarter of the GDP generated in the City of London and around 50,000 jobs. Most of the business is for clients outside the UK, so it is a huge contributor to the UK balance of payments.

The market dates back to the formation of Lloyd’s of London in 1688. The 330-plus years of innovation and evolution since then have witnessed several firsts. For example, the world’s very first motor, aviation and satellite risks were all insured at Lloyd’s and more recently, we’ve also seen the first cyber-risk policy underwritten in London. The market is the first port of call for complex risks, such as those surrounding offshore oil platforms and major construction projects. That said, it is probably best known for insuring unusual risks, such as Taylor Swift concerts, David Beckham’s legs and a prize for the capture of the Loch Ness monster. And yet, despite the size and importance of the London insurance market, it is not well known or understood outside of the EC3 postcode. Politicians, journalists and investors alike all tend to overlook it.

Years of plenty lie ahead for insurers

In the case of investors, this might seem sensible. The insurance industry is notoriously cyclical, with a few years of exceptional profits inevitably followed by long periods of poor returns for shareholders. In this respect the insurance market is like the story of Pharaoh’s dream from the Old Testament book of Genesis. The Pharaoh who ruled Egypt had a series of vivid dreams that were interpreted for him by Joseph. In one such dream, a group of seven fat cows came out of the Nile, followed by another group of seven skinny cows. Joseph explained that this meant there would be seven years of bumper harvests followed by seven years of famine. He told the Pharaoh to build grain stores to hold the surplus food from the bountiful years to help the country through the lean years.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The insurance cycle usually follows a similar “feast and famine” pattern. Unlike many business sectors, it is not driven in the main by the sorts of wider financial and economic factors that drive the financial markets. Instead, it tends to revolve around major catastrophes such as Hurricane Katrina that produce huge claims for the industry. That said, it is possible to predict the development of the insurance cycle with some confidence if you are familiar with the industry. The good news now is that an opportunity is emerging for shareholders to make bumper returns over the next few years, as the cycle moves decisively in insurers’ favour.

The trouble with insurance

Insurance has three major problems that make it a difficult hunting ground for investors. Firstly, insurance is viewed as a commodity, so competition largely centres on price rather than product quality. Much as insurers try to differentiate their products and their claims service, the reality is that buyers do not envisage making a claim. For them, insurance is just a product that they must buy to protect their assets, so the average buyers will simply go for the cheapest option. Secondly, the barriers to entry are low. It is possible to raise sufficient capital and establish a new insurance company with regulatory approval and an A- credit rating in a matter of months, especially in a business-friendly territory such as Bermuda. Finally, and most importantly, the cost of sales is unknown and impossible to predict with any degree of confidence.

When most companies sell a product or service, they have a fairly good idea of how much it costs to make or deliver that product or service. Insurance is different. When an insurance company insures a factory, for example, it has no way of knowing whether or not it will have to pay a claim. Its cost of sales may be close to zero if there is no claim – or extremely high if the factory burns to the ground. To make matters even worse, with liability insurance there can be a long time-lag before claims are made and settled. As an extreme example, claims for diseases resulting from exposure to asbestos are still being made to policies dating from as far back as the 1970s.

As a result, come the end of the financial year the total premium billed by the insurer is relatively easy to calculate, but the total claims that will be paid are at best an educated guess. Most of the policies written during the year are still running and it may be months or years before they expire. It will be much longer still before the claims are all agreed and settled. For this reason, insurers employ teams of actuaries to model the likely ultimate claims total, so they have a plausible estimate to put into the year-end accounts. The firm will have to keep enough in cash and investments to cover this total, which is known as the “reserves”.

This is where the fun starts. The management teams of insurance companies have a fair degree of latitude when it comes to picking a number for the total reserves. They should err on the side of caution and put enough aside comfortably to cover a reasonable worst-case scenario. If in future years the actual claims are lower than the reserves held back, then the surplus reserves can be released to boost the profits of the following year. If the claims turn out to be worse than expected, then the reserves will need to be increased to compensate, which might mean the company makes a loss and in extreme cases needs to raise more capital or goes out of business.

When the insurance market is going through profitable times, a good chief executive will make sure that some of the potential profit is held back to boost the insurer’s reserves in the same way that Pharaoh stored extra grain in his silos. However, it does not take many years of attractive returns from the insurance market before more competition arrives. This may take the form of new insurance companies being formed, or existing ones raising extra capital to enable them to increase market share. The only way to expand quickly is to compete aggressively on price. Before long, premiums are falling significantly year after year. This quickly erodes profit margins.

What happens next is that insurers will tend to raid their reserves to enable them to maintain their profits. To the outside world it looks as though profits are stable. But this in turn attracts yet more competition and reduces pricing still further. Eventually the grain stores (the surplus reserves) run dry and suddenly insurers start making losses. Often at this stage of the cycle the situation is compounded by one or more major disasters, such as a big hurricane that results in a dramatic leap in claims. This results in insurers making large enough losses to affect their capital bases, or even put some out of business. Finally, insurers have to raise prices significantly and the cycle slowly starts to turn again.

Where we sit in the cycle

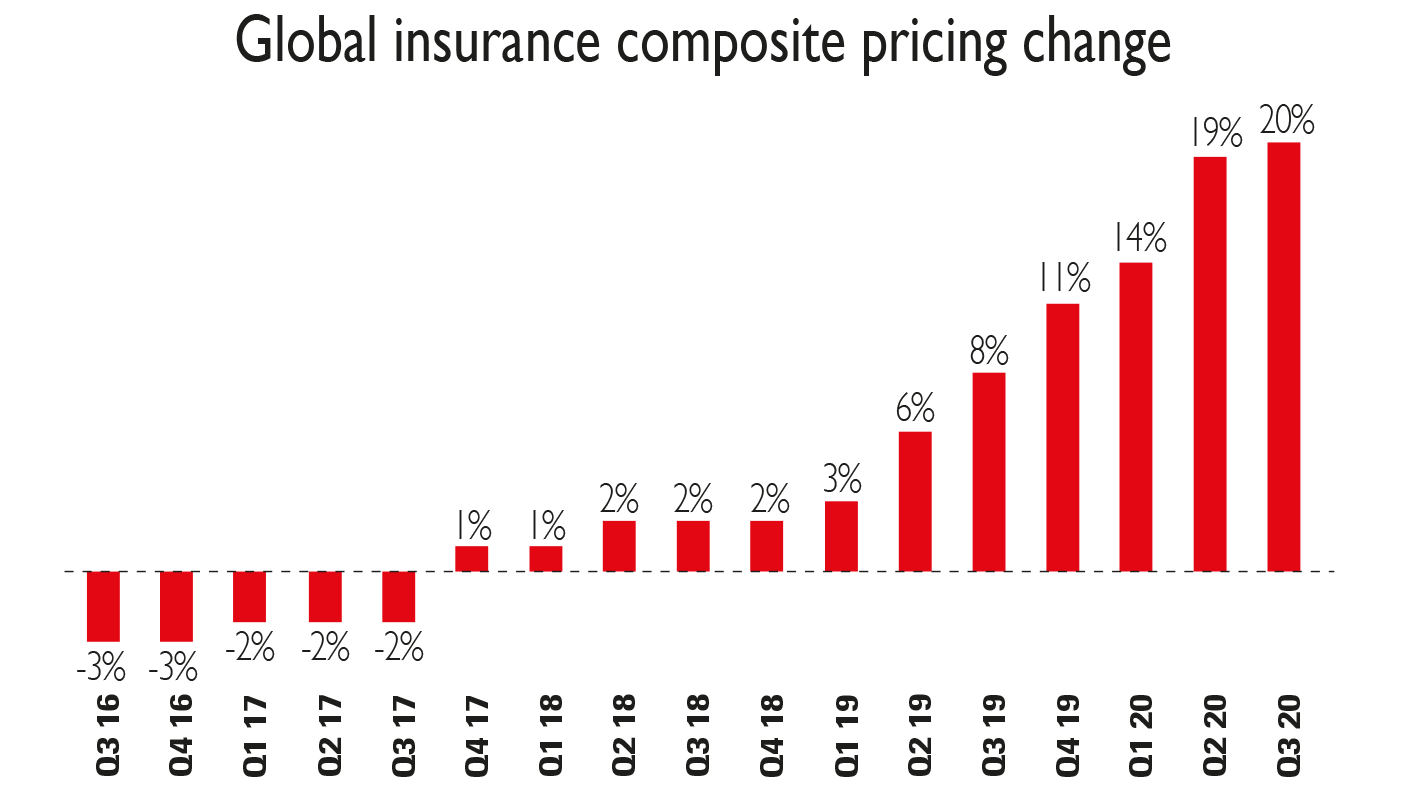

So where are we now in the insurance cycle? Is it time to start investing? According to Marsh Inc., the world’s largest insurance broker, insurance pricing has been rising for the past 12 quarters and is now rising at its highest rate since at least 2012 (see chart). This trend is expected to continue in 2021 with further percentage increases in premiums in the mid- to high-teens. This has yet to show up in the financial results of most insurance companies for two reasons. Firstly, accounting conventions in the sector mean there is a delay in price increases appearing in the accounts, as much of the risk that insurers are exposed to derives from policies written in previous years. So this year’s business at higher rates will mainly benefit the 2021 accounts.

Stormy weather

Secondly, the improved underlying results have been masked by the impact of Covid-19-related claims, which are forecast to total well in excess of $100bn globally. On top of that, 2020 saw a record-breaking 30 tropical storms form in the Atlantic, with many making landfall in the US. The usual collection of names for storms this year was exhausted and meteorologists had to resort to the Greek alphabet, reaching Hurricane Iota in mid-November. The total cost of natural catastrophe claims will be well above average as a result.

However, further premium increases in 2021 will mean that insurers should achieve profitability even in a year with above-average claims. And if it turns out to be a more normal year, then profits could be substantial. Some of the forecast profit will be needed to replenish reserves, so it will be some time before profits will be large enough to attract significant new capital to start the cycle turning downwards. In the meantime, expect several years of increasingly strong results from the major commercial insurance companies and a significant rally in share prices from the current depressed levels. The fat years are on their way. Below I look at some shares that could be best placed to profit.

Nine insurance plays to invest in today

A subsidiary of American International Group (NYSE: AIG) almost caused a global financial meltdown during the great financial crisis of 2008-2009 by betting on complex credit derivatives, before it was bailed out by the Federal Reserve. However, this once-sprawling conglomerate has been slimmed down and restructured by outgoing chief executive Brian Duperreault and is now a more focused operation insuring mid-market to large corporate clients and high net-worth private clients. It is in the sweet spot of the current improving market.

Lloyd’s-based Beazley (LSE: BEZ) has had a bad 2020. Covid-19 losses have hit its conference and event cancellation insurance portfolio and led to two profit warnings and a capital raise. However, it is generally considered one of the smarter Lloyd’s operations, is now cheaply priced and should regain its shine in 2021.

Aim-listed Helios Underwriting (Aim: HUW) is the only pure play Lloyd’s investment. It is effectively a fund that owns shares of some of the best-performing private syndicates in Lloyd’s. It has just completed a share placement that has doubled the size of the company, enabling it to expand aggressively into what it sees as the best opportunity in a generation. The placement was backed by some shrewd institutional managers, such as Polar Capital. (Full disclosure – the author is a shareholder.)

London-listed Lancashire Holdings (LSE: LRE) has both a Bermuda reinsurance operation and a Lloyd’s syndicate. It has a record of superior performance and generous special dividends when results are good. Everest Re (NYSE: RE) and Renaissance Re (NYSE: RNR) are two of the best specialist Bermuda-based reinsurers (see definition on page 22). The higher level of catastrophe claims in recent years has increased both demand for reinsurance and pricing levels. Expect greatly increased profits over the next few years as a result.

Verisk Analytics Inc (NYSE: VRSK) is a possible “picks and shovels” play on an improving insurance market. As a risk-modelling and data-analytics specialist it is working with insurance companies to make the underwriting process more efficient and to help them understand and model their risk exposure.

Those looking for a fund to play the sector should look at the Polar Capital Global Insurance Fund, which Max King examined in detail in the 4 December issue of MoneyWeek.

Another, slightly more tangential way to play the insurance sector is via the holding company for one of the world’s best-known investors – Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.A). The investment vehicle of US investor Warren Buffett is not an insurer itself, but it does own a lot of them. That may seem odd. After all, a key factor Buffett looks for in a firm he might invest in is a clear and sustainable “moat” that makes it hard for other companies to compete. For example, Berkshire’s largest holding is tech giant Apple. This has a huge defensive moat – customers get locked into its ecosystem as all their devices sync with each other and their data and music collections are in the Apple cloud. Insurers, on the other hand, have little or no such moat – as we discuss above, competition is price driven and there are few barriers to entry. Why then is a huge proportion of Berkshire made up of insurance companies (the sector accounted for the lion’s share – 27% – of revenues in the third quarter of November 2020)? The key lies in what Buffett can do with their reserves. Most insurers invest their reserves in “safe” assets, such as investment-grade bonds. Berkshire instead uses the reserves from its insurance companies as a cheap form of “float” for Buffett to fund his investment portfolio. If his insurers can make an underwriting profit (premiums collected exceed claims paid), then his cost of capital is effectively negative.

I wish I knew what reinsurance was, but I’m too embarrassed to ask

Reinsurance is insurance for insurance companies. It is used by insurers to reduce their exposure to major catastrophes. Most insurers operate in a single country or region and so can have concentrated exposure to a particularly costly event, such as an earthquake or hurricane in that territory. In extreme cases this could bring down the insurer. Using reinsurance they can pass on some of their losses above a certain level to other, larger insurers. These reinsurers can build a balanced portfolio by reinsuring insurers across several different territories and different types of risks. In turn reinsurers can pass on their biggest risks in the “retrocession” market. This is the “Wild West” of the insurance world, where the risk may be taken on by lightly regulated funds, in countries such as Bermuda and Switzerland, which are often backed by pension, hedge-fund and family-office capital in search of attractive returns that are uncorrelated with other financial markets.

John Chambers worked in the Lloyd’s market for 33 years in underwriting management. He is now a writer and adviser to private equity.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

MoneyWeek is written by a team of experienced and award-winning journalists, plus expert columnists. As well as daily digital news and features, MoneyWeek also publishes a weekly magazine, covering investing and personal finance. From share tips, pensions, gold to practical investment tips - we provide a round-up to help you make money and keep it.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton