The industry at the heart of global technology

The semiconductor industry powers key trends such as artificial intelligence, says Rupert Hargreaves

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

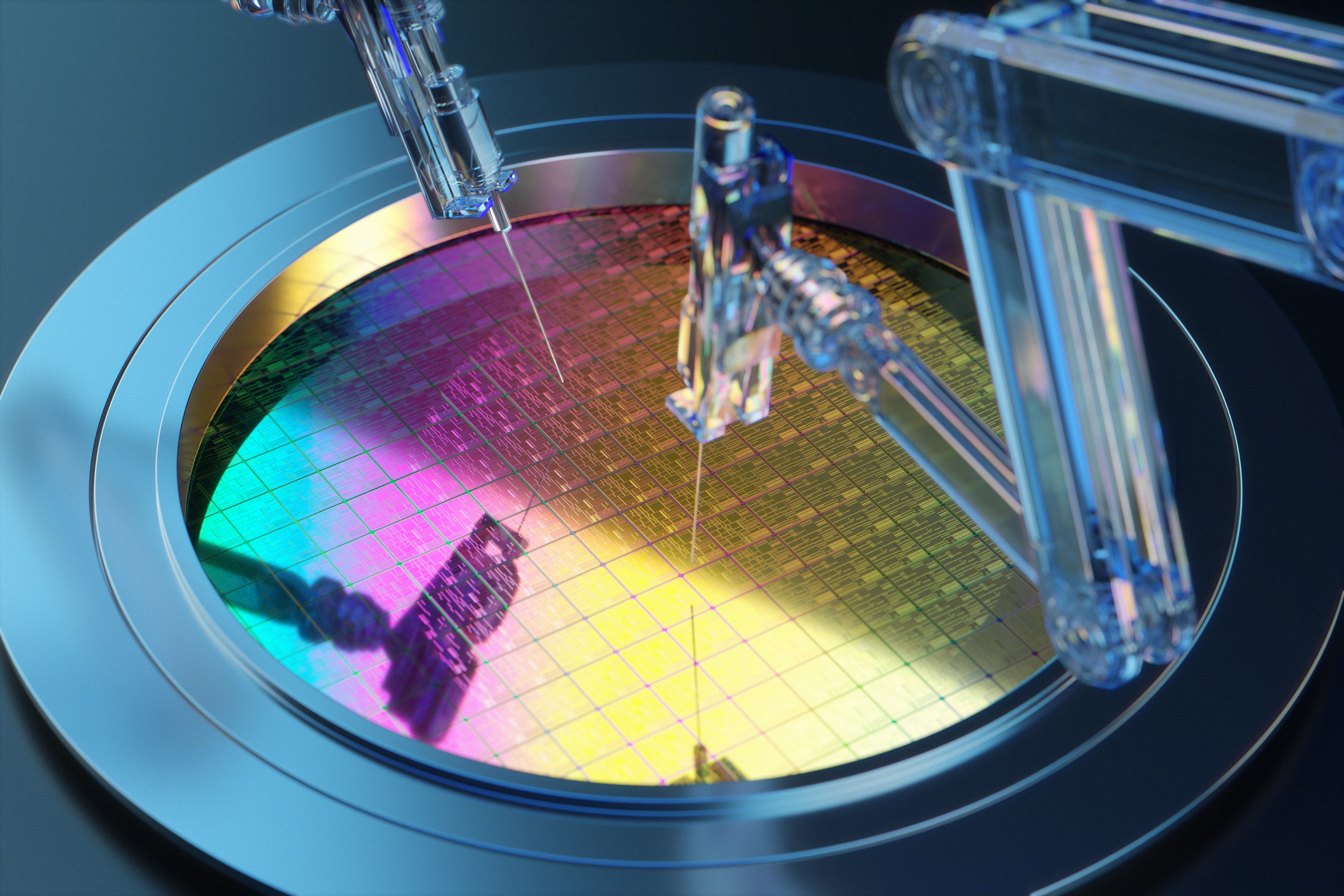

The semiconductor industry is a catch-all term for the broad range of companies that design, manufacture and sell microchips. Microchips, or chips, are a collection of switches controlled by electrical pulses.

These switches are printed onto a board using a semiconductor material, such as silicon, or to a lesser extent germanium. The conductive nature of the board allows components to be etched into the material in layers, along with the connections to facilitate the flow of electrical signals.

The thinner and more conductive the semiconductor material, the more components that can be included and the more powerful the chips. The latest tech allows 50 billion components to be included on a chip the size of a fingernail.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Logic and memory

There are two main types of chips: logic chips, which do the calculations, and memory chips, which store data for use in calculations. Central processing units (CPUs) and graphic processing units (GPUs) form the backbone of the logic-chip market. GPUs are superior to CPUs as they can perform multiple calculations at the same time. These units break down complex calculations and then work on the component parts, making them vital for highly complex repetitive tasks, such as those performed by artificial intelligence (AI).

CPUs and GPUs sit at the core of computer systems, and they perform the central functions. They form the brain of the device. Around the main processors sit the chips that facilitate the functioning of other inputs that feedback into the brain, such as the Bluetooth transmitter or the 5G-network receiver. Most brains can only perform so many calculations, so they need to store data while they process parts of the calculation or other bits of work. That is where memory chips come into play. All of these different chips are extensions of the brain. Without them, the device won’t work and without the brain, the other chips won’t work.

This is a simple overview of how electronic devices work, but it’s enough for investors to understand where the key markets lie. Processors are complex and unique devices that cost billions to develop, and as the performance of the device relies on an efficient processor, that is where the real value lies.

The most advanced form of logic chip currently on the market is Nvidia’s Blackwell B200 GPU. This chip has 208 billion transistors, and Nvidia has designed a platform that can utilise two of its most advanced GPUs, the GB200, a so-called “superchip”. At a cost of $30,000-$40,000, Blackwell (it reportedly cost $10bn to develop) is right at the top end of the logic-chip market. Nvidia’s main competitor is AMD, which has carved out a strong niche in CPUs and GPUs for data centres in the past five years.

Nvidia has become the poster child of the global chip industry, but you might be surprised to learn that this company doesn’t make its own chips. Indeed, Nvidia is what’s known as a “fabless” company, which means it does not own any semiconductor fabrication (fabs) facilities. This isn’t uncommon because fabs are eyewateringly expensive and often unprofitable. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) controls two-thirds of the global semiconductor foundry (a company that owns fabs) market and is the go-to manufacturer for semiconductor designers. But it has to work hard to maintain its advantage. In 2023, it spent $30.4bn developing new and upgrading existing facilities. In 2024, it will spend between $28bn and $32bn. Only a few companies in the world can commit to spending this much cash year after year. And TSMC needs to keep spending as the market is moving so fast.

Intel is one of the few companies that both designs and manufactures chips. It makes central processing units (CPUs) that are used in general-purpose consumer electronics, such as laptops. In recent years, this market has started to deteriorate as CPUs have given way to faster GPUs, so Intel is trying to catch up. It has earmarked $100bn to build new fabs across the US over the coming years. To put that number into perspective, the company’s entire market value is just $172bn. What’s more, the fab business isn’t making money. Intel’s chip-making division accumulated $7bn in operating losses in 2023, up from $5.2bn in 2022, on sales of $18.9bn. Making chips is expensive, and profit is not guaranteed even for the market leaders.

So much for the logic chips, the most exciting subsector of the market. Away from the world of CPUs, GPUs and world-leading fabs, there is another layer of vital, but less exciting companies. These focus on memory chips. This is a business of scale. The three biggest manufacturers in the $160bn memory-chip market are Korea’s Samsung and SK Hynix and America’s Micron Technology.

According to data provider TrendForce, memory chip prices rose by around 20% in the first quarter of 2024 owing to supply cuts and higher demand. Samsung Electronics expects to post a tenfold jump in first quarter operating profit. Micron, meanwhile, expects to earn a record profit in 2025 thanks to its investments in growth and rising memory chip prices. These results show how commoditised and cyclical the industry is.

However, while Samsung has forecast strong growth from its memory chip business, its foundry business is losing money. That illustrates the stark differences between memory chip production and the fabrication of more advanced chips

The smaller subsectors

Alongside the main players in the logic- and memory chip markets, there is a range of chip designers and manufacturers. These generally specialise in chips that perform certain functions in an electronic device, functions the central-brain logic chip is unable to deal with. Take Qualcomm. This is a world-leading player in the market for 4G- and 5G-telecoms chips. It has the technology and the patents for the tech and outsources most of its production, making it a fabless chip company. However, it does produce some wireless connectivity chips in-house. Broadcom is another fabless player, and it also designs communication chips.

This fabless market is huge, and it is arguably where the most progress in the sector is made. Alongside Nvidia, one of the best-known players is Arm Holdings. Arm licenses its chip designs to third parties, who then incorporate them into their own products. Its customers include some of the world’s most valuable AI heavyweights, such as Nvidia, Google’s parent Alphabet, Qualcomm and Microsoft, among others. In many ways, Arm is the chipmakers’ chipmaker.

Arm, Nvidia, AMD and Intel all rely on firms such as Synopsys, which provides software for semiconductor and other electronic systems design. In the same way that many chip designers are fabless, designers often rely on third-party software to help design chips. This streamlines the design and manufacturing process across multiple parties and is a cost-effective way for smaller players to break into the sector.

Synopsys has invested an average of 30%-35% of its revenue on research and development (R&D) in the 37 years since its inception. This helps explain why semiconductors’ productivity has increased by a factor of more than ten million in 37 years.

The semiconductor industry, then, is highly diverse, with multiple companies playing a role in the design and development of one model of chip. The number of companies involved in producing components for a device such as an iPhone is mind-boggling. At the last count, Apple had nearly 200 direct suppliers for the hundreds of parts that go into each of its products. That’s without including the suppliers’ suppliers.

A new growth cycle

The world is currently on the edge of a big shift when it comes to computing power. AI is just starting to take off, and over the next few years, analysts believe we will see an upswing in capital expenditure as older systems are replaced with newer, more powerful chips that can deal with AI’s demands.

Accounting and consultancy group Deloitte forecasts a 13% rise in the industry’s revenue this year to $588bn. Demand for AI chips is expected to grow at an annual pace of 38% to 2032, generating yearly sales of $372bn at the end of the period. Part of this growth will stem from AI custom chips, designed by individual companies to complement expensive GPUs. UBS believes this market will expand from 2%-3% of the market today to as much as 10% by 2029.

At the same time, there will be a growing demand for AI edge computing, according to UBS. This involves AI processes being conducted by a local device rather than by a distant server, speeding up processing and reducing demand for power. Due to the cost and supply-chain bottlenecks, much AI work is currently done in the cloud or via centralised servers managed by the likes of Microsoft and Alphabet. This won’t go away, but the nature of the customer will shift. Bigger, deeper-pocketed companies will build their own systems in-house, while smaller firms, which have yet to invest in AI, will rely on the cloud.

These three market tailwinds will benefit the whole sector. But there is one part of the industry I have not covered yet that UBS believes is best placed to profit: so-called semiconductor capital equipment companies. These develop and produce the manufacturing equipment needed for semiconductor chip production. “As a hardware refresh cycle picks up,” UBS notes, “and greater demand for semiconductors follows through 2025, we believe foundries and semiconductor manufacturers will invest in the infrastructure and equipment required to boost output.”

According to industry association SEMI, 42 new fabs are expected to go online this year. That would be a big jump from 29 fabs in 2022 and 11 last year. As more fabs open, the semiconductor-manufacturing equipment market is predicted to generate revenue of $154bn in 2028 compared with $84bn in 2021. Remember, the semiconductor industry is huge, and there are many players in each stage of the value chain. If you wanted to avoid one company in the process of designing and building a chip, you probably could, but that’s not possible at the capital equipment stage.

The Netherlands’ ASML dominates the market for lithography equipment used in the semiconductor industry. Lithography is the process of etching components onto silicon chips, and the more advanced the microchip design, the more technical the process of lithography becomes. ASML’s lithography machines are some of the most advanced ever created by humans.

Its latest range of dual-stage extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography systems are the most advanced manufacturing systems in the most developed manufacturing sector. ASML has a market share of 80% in the lithography-system market. Its major rivals are Japan’s Nikon Corporation and Canon, but neither of these companies has managed to commercialise EUV lithography systems, so ASML is the only provider.

Applied Materials provides advanced equipment to chip manufacturers. While not a monopoly like ASML, it is a leader in the sector, with 55 years of research and development under its belt. The applied services division is key. It helps customers deal with increasingly complex manufacturing processes, keeping fabs running around the clock.

What to buy now

There are plenty of ways investors can gain access to the growth of the semiconductor industry over the next decade and beyond. However, owing to the size of the industry and the different roles companies within it play, an investment trust might be the best option.

As Nicholas Todd, investment trust research analyst at investment advisor Kepler Partners notes, “semiconductors are at the core of mega-trends, including increasing social connection via digital networks, artificial intelligence, cloud computing and data storage, and electric vehicles”.

Todd highlights the Allianz Technology Trust (LSE: ATT), managed by Mike Seidenberg, and the Polar Capital Technology Trust (LSE: PCT), managed by Ben Rogoff, both of which have “above-benchmark exposures of over 30%” to the semiconductor industry. As well as exposure to the semiconductor poster child Nivida, they also hold technology stalwarts Microsoft, Meta and Amazon.

Polar Capital has a “more benchmark-aware, diversified approach, with over 100 names” in its portfolio, while Allianz Technology “takes a higher conviction, more benchmark-agnostic approach”. The higher-conviction approach reflects the manager’s “‘winner-takes-all’ view of the technology sector”.

Seidenberg “looks to take advantage of cheaper valuations further down the market-cap spectrum that could benefit from secular growth trends, including Monolithic Power Systems, which designs and develops semiconductor-based power solutions, and Micron Technologies, which produces memory and storage technology. Seidenberg also looks to invest in what he calls “derivative plays” across the sector that provide key inputs, “such as Lam Research”, Todd says.

Although Polar Capital’s fund has outperformed this approach, Allianz Technology’s manager has only been in the role since 2022, when he took over from his predecessor, Walter Price. Both trusts are trading at discounts of 9% to net asset value (NAV), offering an opportunity to buy a portfolio of tech names at a deep discount to their prevailing market values.

It may be worth sticking with the market’s leading stars if you’re willing to be a bit more adventurous and pick winners in the sector. Developing the most advanced chips and building foundries is hugely expensive, putting them both out of reach of all but the sector’s biggest players. TSMC (NYSE: TSM) looks to be the best place for exposure to the manufacturing fabrication market, although the fact that most of its facilities are located in Taiwan is a risk.

If China does choose to invade the island, TMSC will lose the bulk of its capacity overnight (it’s even been reported, although not confirmed, that in this scenario the company has rigged its fabs to self-destruct). Samsung (Seoul: 005930) also has the firepower to compete. Its fab footprint is spread across its home market in South Korea and the US, as well as a handful of other Asian nations, such as Vietnam and China.

One company I have not yet mentioned in this article is Texas Instruments (Nasdaq: TXN). Texas is, alongside Intel, the most renowned company in the world of semiconductors. Founded in its present form in 1951, it’s a few years younger than Fairchild Semiconductor (founded 1957), which invented the silicon semiconductor. Intel was then co-founded by Gordon Moore (known for “Moore’s law”) and Robert Noyce, who left Fairchild in 1968.

While other companies have chased growth by developing expensive logic chips or competing on the cost of memory chips, Texas has carved out its niche with analogue and embedded chips. These are relatively simple, but vitally important chips designed and programmed to perform one task, such as operating a component in a robotic arm or an MRI machine, or the flaps on the wing of an aircraft.

Demand for these components will grow exponentially as the world becomes more and more reliant on machines. A robotic arm, for example, may only use one AI brain to control it and the rest of the production line, but each machine may have hundreds or thousands of less complicated chips embedded in the arm to make it work.

Texas is investing $5bn a year over the next few years to build out its fabrication base for these chips and will continue to invest billions each year thereafter. It stands out as an investment because of its record of shareholder returns. Over the past 20 years, it increased its dividend at a compound annual rate of 24% and repurchased 40% of its outstanding shares. Over the past 15 years, the stock has returned 17.9% per annum. Texas is in the sweet spot of having enough cash to provide a healthy return to investors while also investing for the future. ASML (Amsterdam: ASML) and Synopsys (Nasdaq: SNPS) also look to be well-placed to profit from the industry’s growth, with monopoly-like positions, deep pockets and well-established positions in the value chain.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Rupert is the former deputy digital editor of MoneyWeek. He's an active investor and has always been fascinated by the world of business and investing. His style has been heavily influenced by US investors Warren Buffett and Philip Carret. He is always looking for high-quality growth opportunities trading at a reasonable price, preferring cash generative businesses with strong balance sheets over blue-sky growth stocks.

Rupert has written for many UK and international publications including the Motley Fool, Gurufocus and ValueWalk, aimed at a range of readers; from the first timers to experienced high-net-worth individuals. Rupert has also founded and managed several businesses, including the New York-based hedge fund newsletter, Hidden Value Stocks. He has written over 20 ebooks and appeared as an expert commentator on the BBC World Service.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement today (3 March). What can we expect in the speech?

-

Three Indian stocks poised to profit

Three Indian stocks poised to profitIndian stocks are making waves. Here, professional investor Gaurav Narain of the India Capital Growth Fund highlights three of his favourites

-

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’Opinion UK small-cap stocks could be set for a multi-year bull market, with recent strong performance outstripping the large-cap indices

-

Hints of a private credit crisis rattle investors

Hints of a private credit crisis rattle investorsThere are similarities to 2007 in private credit. Investors shouldn’t panic, but they should be alert to the possibility of a crash.

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’Opinion Bitcoin and gold are both monetary assets and tend to move in opposite directions. Here's why you should hold both

-

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new look

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new lookThe beauty industry is proving resilient in troubled times, helped by its ability to shape new trends, says Maryam Cockar

-

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?Energy provider SSE is going for growth and looks reasonably valued. Should you invest?

-

Has the market misjudged Relx?

Has the market misjudged Relx?Relx shares fell on fears that AI was about to eat its lunch, but the firm remains well placed to thrive