Great financial disasters in history: the collapse of Overend Gurney

When 18th-century bank Overend, Gurney & Company's business loans started losing around £500,000 a year, it went bust, landing shareholders with a bill of £2.5m.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

In 1775 the Gurney family of Norwich founded Gurney & Co, which grew to become one of the most successful banks in East Anglia. In 1807 the family bought London bill broker Richardson, Overend & Company – a business that bought and sold bills of discount (effectively short-term business debts). The merged firm became Overend, Gurney & Company. From around 1859 the bank, then the largest bill broker in England, expanded by making more general business loans to a variety of enterprises.

What went wrong?

Overend Gurney’s bill-brokerage business was profitable, but its forays into more general business loans proved disastrous, and it lost around £500,000 a year from 1860 onwards. By 1865 it was hopelessly insolvent. To protect the bank the partners decided to sell the business to a new limited company that was then listed on the stock exchange. As well as promising a “highly remunerative return”, the prospectus promised that any losses would be fully guaranteed by the sellers.

What happened next?

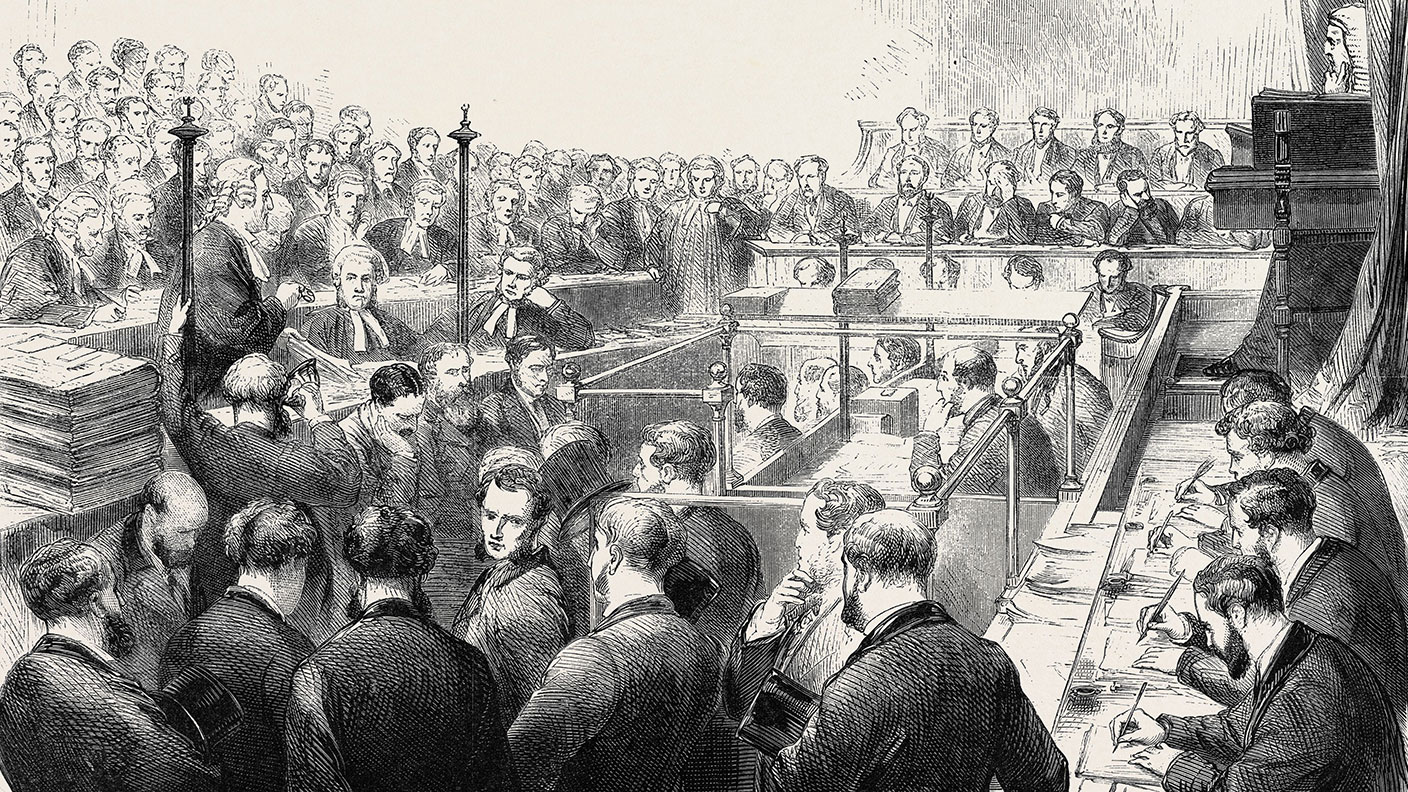

By the spring of 1866, people were speculating about the scale of potential loan losses and Overend Gurney’s directors realised that the company could not survive. After the Bank of England refused to give it an emergency loan, Overend Gurney ceased operation, causing a general financial panic that was only quelled when the Bank of England injected £4m (£385m in today’s money) into the system. In the ensuing bankruptcy it quickly became apparent that the losses on the loans far exceeded any guarantees, leaving shareholders liable for the rest. A private prosecution was launched against the directors. But although they had clearly made bad business decisions, the directors were acquitted of fraud in 1869.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

Overend’s creditors would be fully compensated; its 2,000 shareholders were less lucky. The shares, which were worth £25 at their peak in October 1865, were worthless by the end; shareholders also had to stump up an additional £25 a share based on the agreement at the initial public offering, landing them with a total bill of £2.5m, causing some of them to go bankrupt. The fact that the prospectus for the offering in 1865 was less than 300 words long, and didn’t contain a balance sheet or any accounts, should have raised some questions.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?Graduates are complaining about their levels of student debt so should wealthy parents be helping them avoid student loans?

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleriesThe best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries – from a 15th-century house in Kent, to a four-storey house in Hampstead, comprising part of a converted, Grade II-listed former library

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brands

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brandsConsumer brands no longer impress with their labels. Customers just want what works at a bargain price. That’s a problem for the industry giants, says Jamie Ward

-

A niche way to diversify your exposure to the AI boom

A niche way to diversify your exposure to the AI boomThe AI boom is still dominating markets, but specialist strategies can help diversify your risks

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom