NFTs – the blockchain art frenzy

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) became big business for the art world in 2021. Chris Carter reports

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

If there was one word, or rather one acronym, that defined the world of collectables in 2021, it was NFT (“non-fungible token”). And it was artist Michael Winkelmann, better known as Beeple, who lit the blue touchpaper in March. For while NFTs – unique digital artworks, or indeed, pretty much anything that can be rendered into a computer file – had been around for a few years already, it was the auctioning of his work Everydays: the First 5000 Days (2021) for $69.3m (£52.3m) that led to the explosion of interest in all things crypto.

NFTs are the artsy sister of bitcoin, with which it shares blockchain technology. To demur was to be left behind. Blockchain art became the coolest thing since American pop artist James Rosenquist painted sliced bread in 1964. All you needed was a computer and an internet connection. Amid the frenzy, an original Banksy was burned so that it could live on solely in the digital realm. The NFT sold for $382,000. (The print was called Morons.)

NFTs go mainstream

Nobody was talking about the Botticelli that sold for £92m in January anymore. Out with the Old Masters, in with the new. Even top-tier auction houses, led by Christie’s, were falling over themselves to relieve collectors of their ether – the art collector’s cryptocurrency of choice – lest they be overtaken by upstart start-ups. Credit-card giants, too, sat up and took notice.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In August, Visa, with its $373bn market cap, announced it wasn’t so much as testing the water of crypto-finance as “jumping in feet first”, according to Visa’s crypto expert Cuy Sheffield. It did this by buying a “CryptoPunk” – one of 10,000 tiny pixelated images of heads that are all slightly different – for a reported 49.5 ether, or roughly $150,000 in old money. Visa was trying to gain an “understanding of the infrastructure requirements for a global brand to purchase, store, and leverage an NFT”, while also “[signalling] our support for the creators, collectors and artists driving the future of NFT-commerce”, Sheffield said.

Within an hour of the purchase, another 90 CryptoPunks, which in August sold for an average of around $199,000 each, had been sold, reported Artnet News. The corporate endorsement had been well received. As recently as last Friday, another CryptoPunk – PUNK #4156, one of 24 “Ape” punks – reportedly sold for 2,500 ether at auction, equivalent to $10.2m. It had been bought in February for “just” 650 ether, netting the seller a $9.8m profit.

Physical or digital

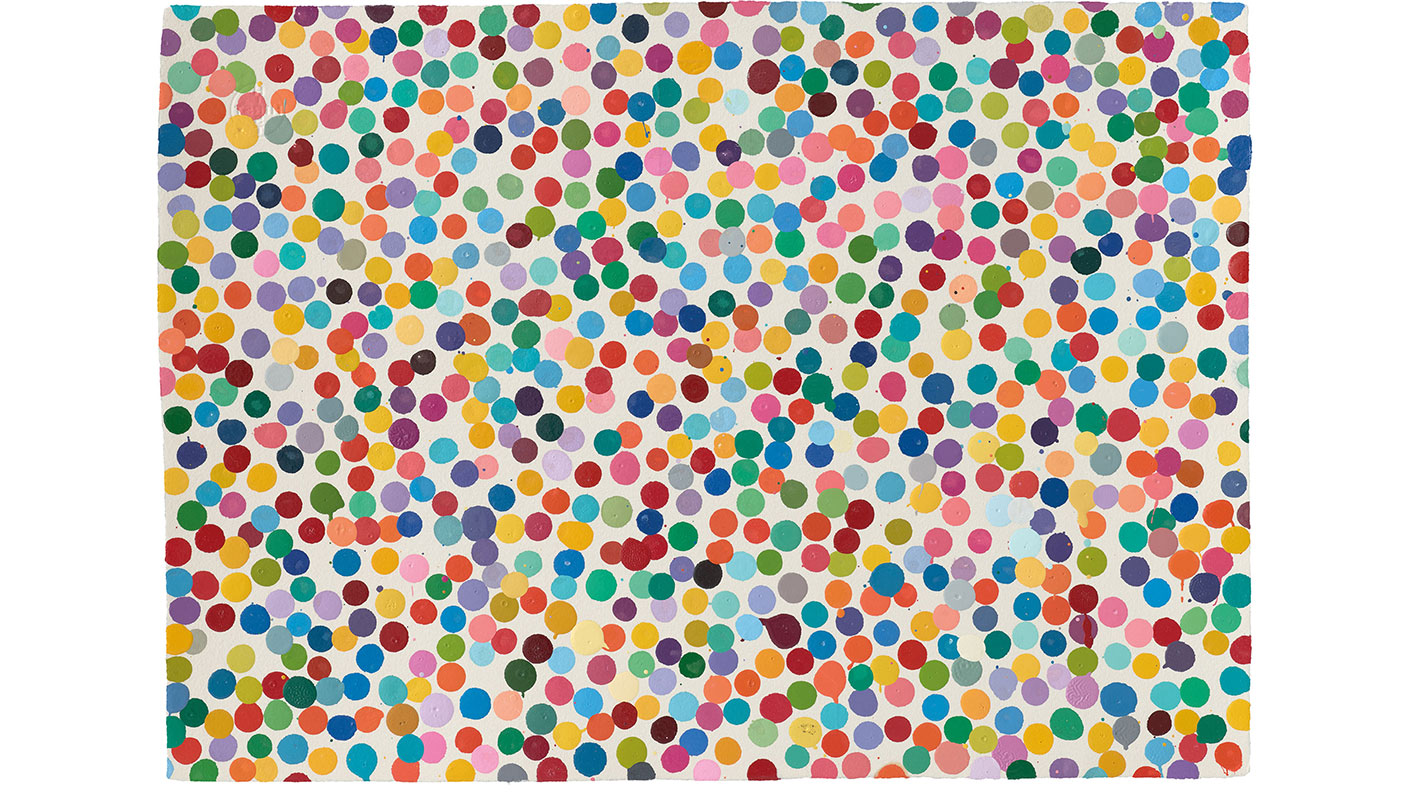

Money isn’t just changing hands, then – it’s changing. Visa hasn’t been alone in running experiments into what the future heralds for NFTs. Damian Hirst has too. In July, the artist sold 10,000 almost identical spot paintings – the same number as CryptoPunks – to the public for $2,000 each.

The buyers can either choose to keep the physical paper versions, which, like pound notes, come with watermarks and holograms, or they can choose to keep the digital NFT version. But they can’t keep both. Choose the paper version and the NFT gets deleted from the digital ledger next July. Choose the NFT, and, like the Banksy above, the corresponding physical artwork gets incinerated. All in the name of economic theory. Former Bank of England governor Mark Carney was even on hand to lend credence to the project – which Hirst calls The Currency – by interviewing the artist about his motives and what he hoped to achieve.

The future of philately

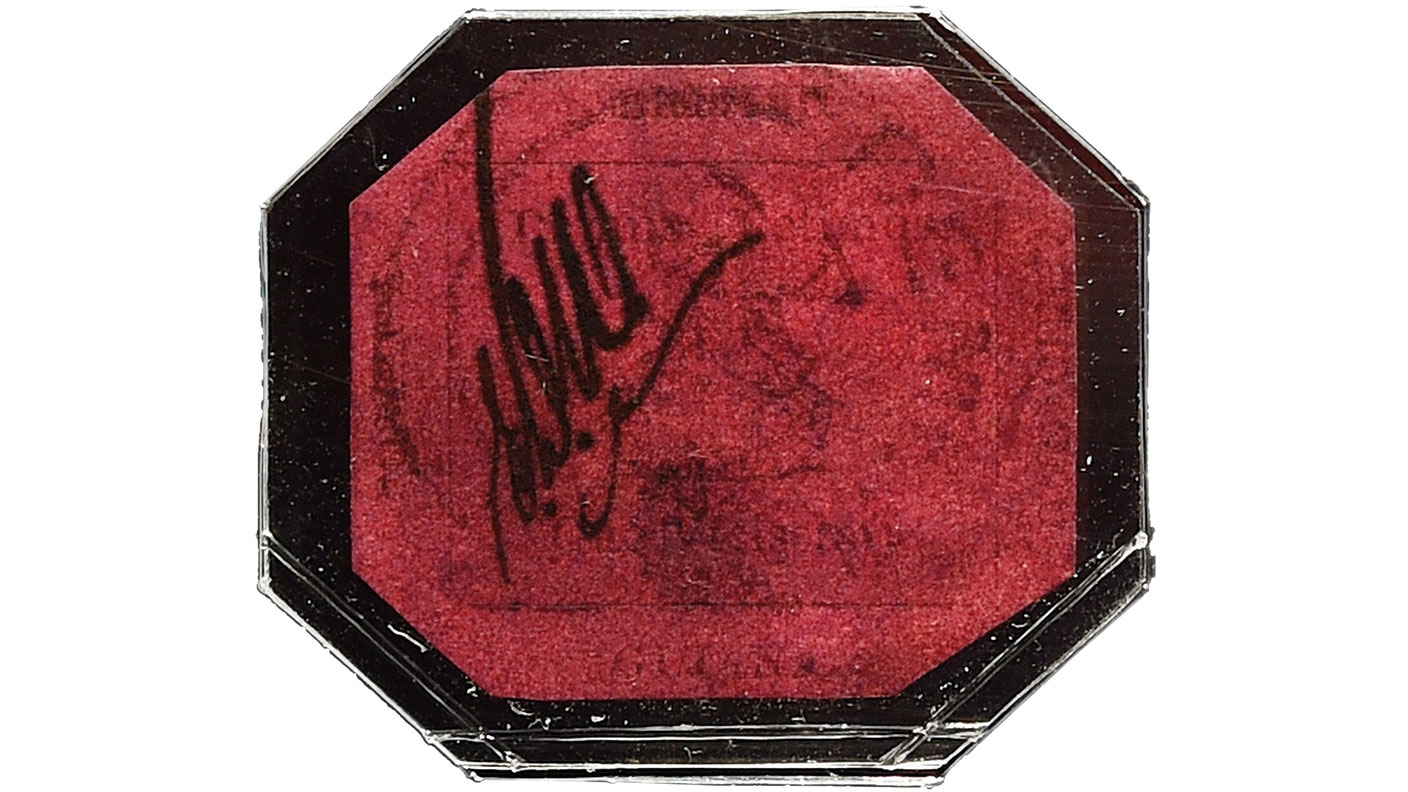

Stamp dealer Stanley Gibbons will be hoping collectors haven’t completely given up on physical assets. In June, the company took a gamble by buying the only known example of the British Guiana 1c Magenta at Sotheby’s in New York for $8.3m. After flying the

1c Magenta back to London, the dealer launched its fractional ownership scheme last month, whereby collectors are invited to buy a share of the tiny stamp, which is, gram for gram, said to be the most valuable man-made object in existence. And yet no secondary market was announced at the time, making it harder for owners to sell their shares – something a digital ledger (ie, the blockchain) could have facilitated.

But why bother owning the “Mona Lisa of the stamp world”, as the 1c Magenta has been called, when you can own the “Everydays of stamps”? Late last month, the online shop of Swiss Post crashed due to demand for its new “crypto stamp”. Buyers can purchase a regular physical stamp for CHF 8.90 (£7.30). With it, they get a digital version depicting one of 13 designs, which they are free to collect and trade. Thankfully, there is no requirement to burn the physical stamps – owners are at liberty to affix them to their Christmas cards in the usual way. Who knows, the idea could even spark a revival in old-style stamp collecting, which has been stuck in the doldrums for several years. Crypto stamps may even be the future of philately. Stanley Gibbons should take note.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton