Ben Cohen: The Ben & Jerry’s co-founder who wants to break away from Unilever

Ben Cohen of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream is seeking to break away from Unilever, the conglomerate he sold out to in 2000. It’s a battle for the soul of the brand synonymous with corporate do-gooding.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Unilever’s decision to spin off its ice cream business marks the end of a fraught 25-year partnership with Ben & Jerry’s that must rank as “one of the corporate world’s most acrimonious relationships”, says The Wall Street Journal. Now Ben Cohen, who co-founded the business with Jerry Greenfield in 1978, wants to stop it being sold or floated along with other Unilever brands. His message to the conglomerate? “If you love us, let us go.”

Cohen’s buy-back bid – he is still trying to line up “like-minded investors” – is “a long shot”. Unilever has made it clear B&J is an essential component of its ice-cream bundle. Moreover, market carnage as a result of Donald Trump’s tariffs has put almost all deal-making on hold.

But perhaps the growing ideological divide in corporate America will work in Cohen’s favour. “Even as a break-up approaches, salvos between Ben & Jerry’s independent board and the parent company continue to fly” – over Gaza, the brand’s “social mission” and “whether to criticise the Trump administration”. There was a big brouhaha last month when Unilever ousted chief executive David Stever, a B&J lifer, for his alleged “activism”, notes the BBC. The Ben & Jerry’s board is suing. It’s also fighting a separate suit defending its right to take on Trumpism. Inheriting this legally messy situation is a big ask for any buyer.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

When Ben and Jerry, who met at school in Long Island, first opened their doors in May 1978 in a converted gas station in South Burlington, Vermont, they weren’t planning to become “major leaders in super premium ice cream” or social activists, says Time. The main motive was to make some cash. Both founders were 27. “Cohen wasn’t having much luck selling his pottery, and Greenfield had been rejected by medical schools.”

They started the business with $4,000 each and another $4,000 from a bank loan, choosing Burlington because of its large student population. The initial plan was to open a bagel shop, but the machinery costs were too high, so they learned how to make ice cream instead. Sales soared. Ben & Jerry’s combined “intensely flavoured, chunky and creative ice creams” with funky-named flavours such as Cherry Garcia, Whirled Peace and Wavy Gravy – packaged in cartons showing “a picture of the two bespectacled bushy-haired owners” looking like “refugees from a sixties commune”. The combination of wholesome wackiness and delicious natural ingredients tapped a nerve. In just a decade, sales hit $3.6 million.

The battle for Ben & Jerry’s “soul”: what will Ben Cohen do?

“The story of Ben & Jerry’s is a legend in two acts,” noted the Stanford Social Innovation Review in 2012. In Act One, the company was “a kind of corporate hippie” – “fair to employees, easy on the environment and kind to its cows”. In Act Two, set in 2000, the mood soured. The founders were accused of selling the company’s soul when they gave in to Unilever’s $326 million offer. Cohen, now 74, believed the strict terms of the sale – which provided for a fully independent board, retaining decision-making over its social mission and marketing – were the brand’s saviour. “If not for that agreement, Ben & Jerry’s would have died by now.”

But the structure was also a recipe for long-running spats, says the WSJ, which erupted into public view in 2021 when Ben & Jerry’s halted sales of its products in Jewish settlements in the Israeli-occupied West Bank in protest at the treatment of Palestinians. Unilever, which claimed to have lost millions of dollars in value as a result of the row, later sold the local business to its Israeli distributor – prompting the first of many lawsuits. That began a battle for Ben & Jerry’s “soul”, which has now resurfaced in sales negotiations. “Business is the most powerful force in our society, and for that, it has responsibility to the society,” says Cohen. Don’t expect him to back down without a fight.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

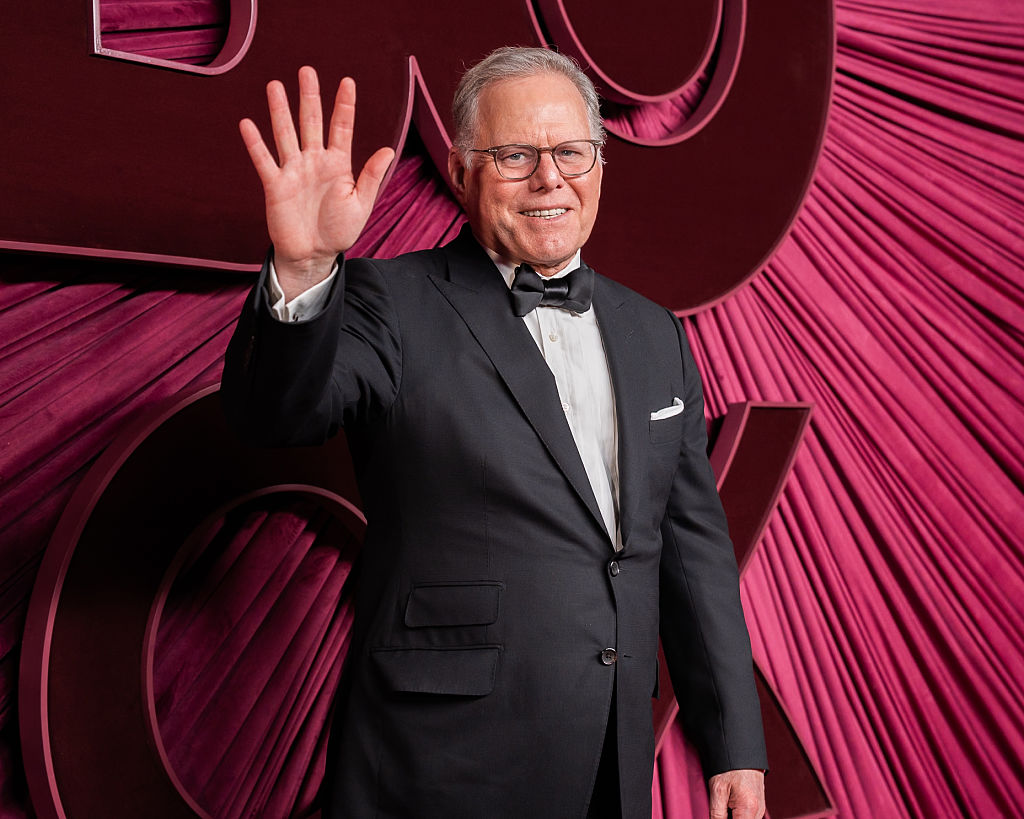

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi

-

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction markets

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction marketsLuana Lopes Lara trained at the Bolshoi, but hung up her ballet shoes when she had the idea of setting up a business in the prediction markets. That paid off