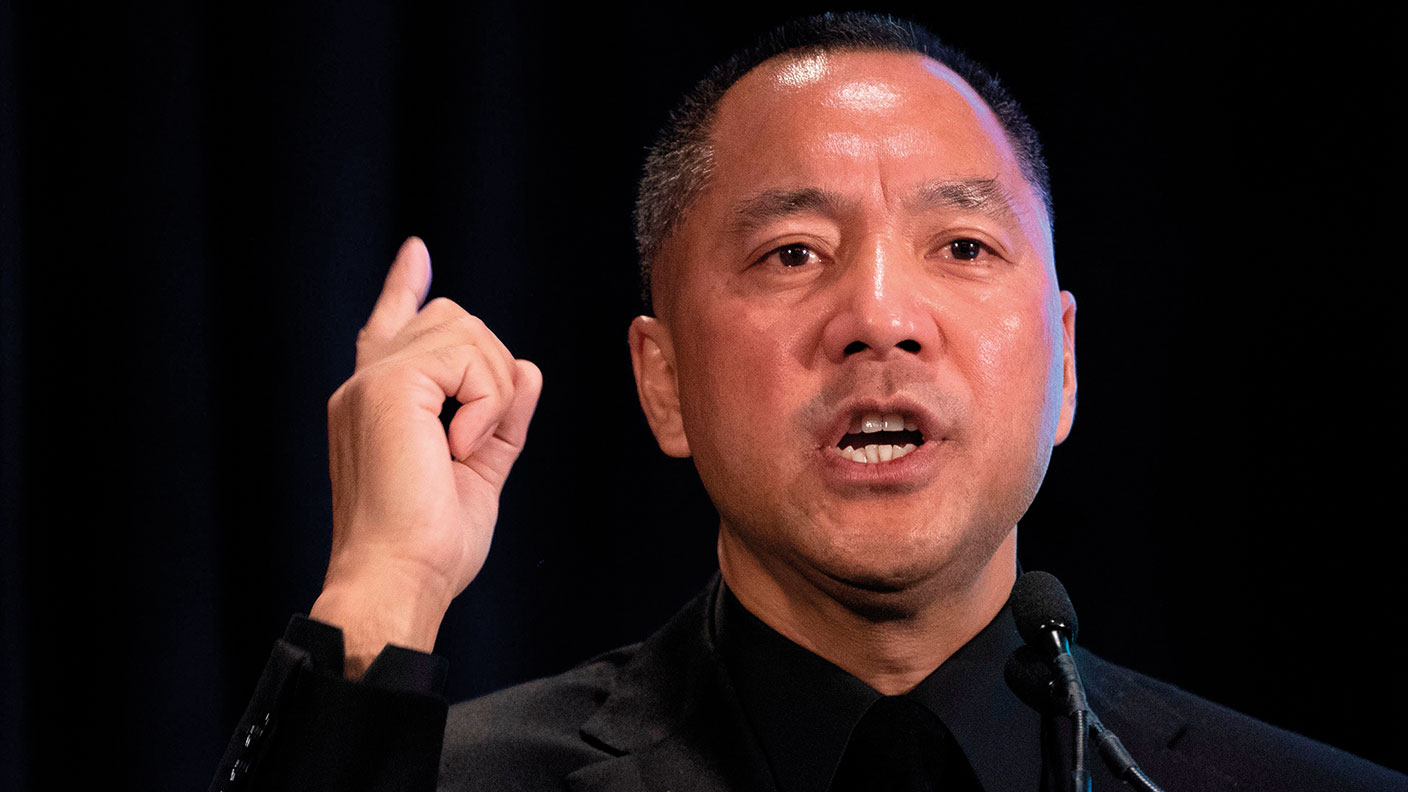

Guo Wengui: a Manhattan caper worthy of a spy thriller

Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui fled Xi Jinping’s regime to claim asylum in the US. But now the American authorities are after him too.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

When it comes to nautical notoriety, the Lady May, a 151-foot aluminium superyacht registered under the Cayman flag, is not quite up there with Robert Maxwell’s Lady Ghislaine. But it is getting there. The vessel, owned by the exiled Chinese billionaire, Guo Wengui – an ally and business partner of Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s political strategist – was the scene of Bannon’s dramatic arrest in August 2020 on fraud charges. Now it is the centrepiece of Guo’s fight for financial survival, says Bloomberg. Earlier this month, a New York court ordered the businessman to pay $134m in fines “for moving and keeping the yacht out of reach” of his US creditors. Guo responded by filing for bankruptcy protection last week.

A useful bargaining chip

Litigation has become something of a way of life for Guo (also known as Kwok Ho Wan and Miles Kwok), a property developer turned prominent critic of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), who fled the country in 2014 to seek asylum in the US, says The Wall Street Journal. On landing in New York, he bought a sumptuous 15-room condo on top of Fifth Avenue’s Sherry-Netherland hotel (now up for sale at $45m), set up a series of small media companies, and began waging a very public crusade to expose the corruption and scurrilous goings-on at the top of the CCP. Despite Guo’s somewhat comedic appearance – he posed for photographs clutching a white Persian cat like the Bond villain Blofeld – his actions had big consequences, says the Financial Times. In 2017, “China’s most aggressive dealmaker”, HNA (then ramping up its Western interests with stakes in Deutsche Bank and the Hilton hotel chain), was stopped in its tracks after a series of explosive but unsubstantiated claims shone an unwelcome spotlight on its affairs.

Guo alleged, via live video stream, that HNA was “secretly owned” by Wang Qishan, the party’s top anti-corruption official and a close associate of president Xi Jinping, along with salacious details about Wang’s love life. An increasingly rattled Beijing responded with first an Interpol red alert for his arrest, and then an attempt to woo him back by promising to unfreeze his assets in China. Trump reportedly considered deporting him, but was persuaded that Guo was a useful “bargaining chip” in his wider stand-off with Beijing, says The Wall Street Journal. By then Guo had been adopted as something of a mascot by “China hawks” like Bannon.

Article continues belowTry 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

A real-life spy thriller

Given his own mysterious background, it isn’t surprising that Guo has attracted plenty of conspiracy theorists himself, says Politico. “Many basic details of his biography…remain hazy.” Born roughly 50 years ago in either Shandong province, or the Jilin province (reports differ), he made a fortune from the construction boom around the 2008 Olympics, developing “a reputation for playing hardball” by smearing anyone who stood in his way. Guo owed his rise to links with top officials, but a move into finance prompted his apparent downfall, says the FT. He quit China after a major clash at the prominent securities firm Founder Group. China later accused him of involvement in at least 19 major criminal cases, involving bribery, kidnapping, fraud and rape.

Is Guo who he says he is? Some doubt it, including US research firm Strategic Vision (which he hired, then fired); it alleged in 2019 that he is in fact a Beijing-backed spy – a “dissident hunter”, posing as “a dissident”. Those claims, while vigorously denied, have rather taken the shine off Guo’s US media career. But right now, money and legal worries dominate. Last September, three of his companies, including GTV Media (where Bannon is a director), were forced to pay $539m to settle charges of illegal securities and cryptocurrency sales. Guo’s murky backstory and “Manhattan caper” is “worthy of a spy thriller”, says the WSJ. There may be more chapters to come.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.