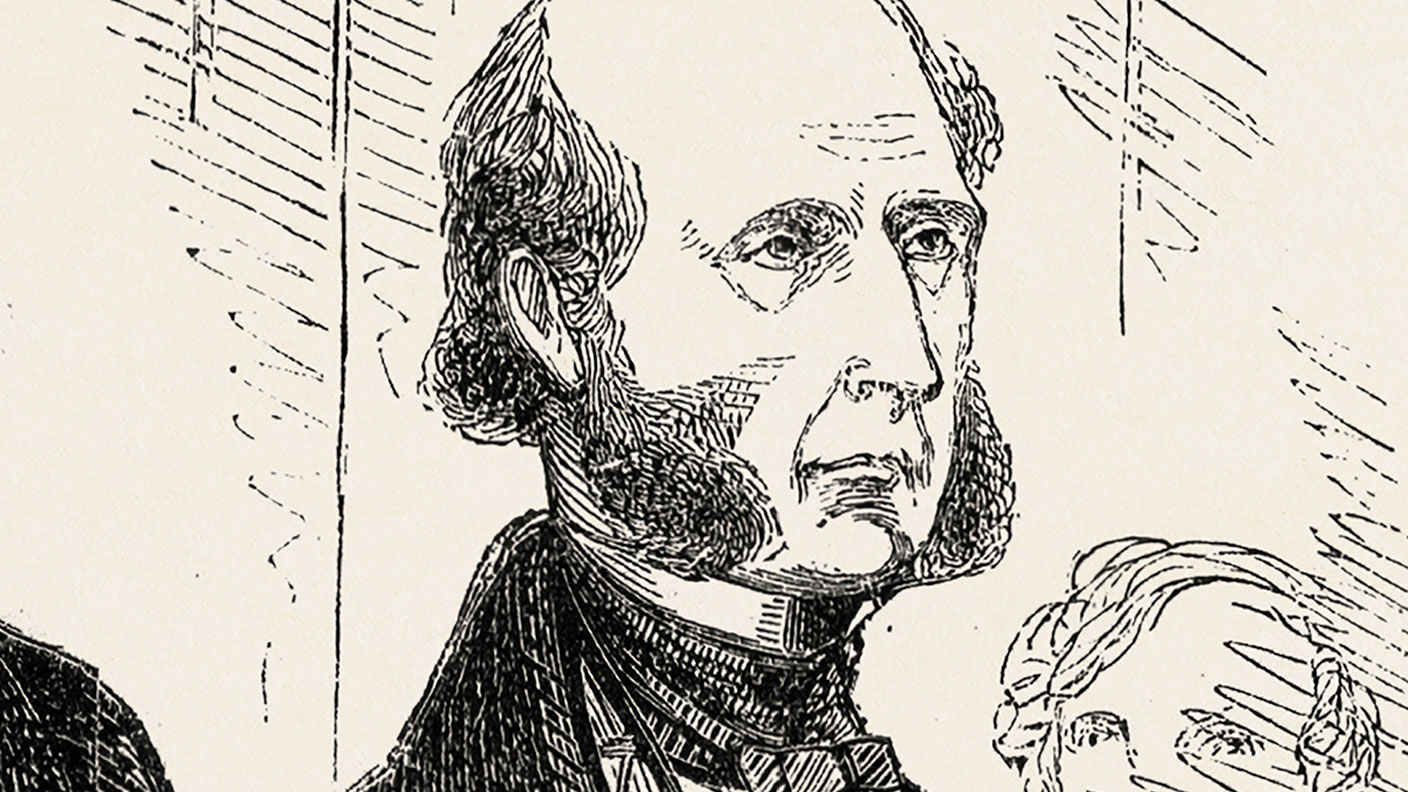

Great frauds in history… William Strahan’s stolen bonds

Eton-educated William Snow, AKA William Strahan, inherited a huge fortune and joined the family bank. On the face of it he was a pillar of respectable society. But he and his partners sold investors' assets to bail themselves out when they went broke.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

William Snow was born in 1807, going on to study at Eton and Cambridge before changing his name to William Strahan in 1830 in order to inherit a large fortune of around £200,000 (equivalent to £18m today) from his great uncle. Two years later he joined the family bank (then known as Snow, Snow, Strahan, Paul and Paul) as a partner. Over the next two decades his wealth and social position led to his being granted the honorary title of High Sheriff of Surrey as well as being appointed to the boards of various companies.

What was the scam?

By 1850 the bank was barely solvent, even taking into account the partners’ personal assets. Over the next few years things got even worse as they made large loans to support various unsuccessful projects, including railways in France and Italy, as well as a colliery in Mostyn in Wales, which ended up requiring increasing amounts of cash. In desperation they sold bonds that they were keeping on behalf of clients, hoping that they would be able to buy them back before the clients noticed that they were missing.

What happened next?

By 1854 Strahan and his two other partners, John Dean Paul and Robert Makin Bates, had run out of money to steal and rumours were flying around London that the bank was insolvent. John Griffith, canon of Rochester Cathedral and one of the bank’s oldest clients, went to the bank’s offices and demanded to withdraw £5,000 (£472,000 today) in bonds that they held on his behalf. Strahan confessed that the bonds had been sold, along with other bonds totalling £100,000 (£9.45m). Strahan and the other two partners were arrested, convicted and sentenced to 14 years in prison (though this was later reduced to three years).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

By the time the bank collapsed, its liabilities were £652,593 with only £127,670 in assets, leaving a deficiency of £524,923 (£49.5m). The bank’s depositors and creditors got some of their money back through the liquidation of the partners’ estates, but they would have to wait more than two decades, and even then would only get a fraction of what they were owed. Given that the bank’s dire position was mostly due to bad loans to two firms totalling £483,000 (£45.7m), the bank’s lending portfolio was clearly not diversified enough. The bank should also have been more ruthless in cutting its losses, rather than lending more money to doomed projects.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Japanese stocks rise on Takaichi’s snap election landslide

Japanese stocks rise on Takaichi’s snap election landslideJapan’s new prime minister Sanae Takaichi has won a landslide victory in a snap election, prompting optimism that her pro-growth agenda will benefit Japanese stocks

-

Alphabet 'is planning a 100-year bond': would you back Google for 100 years?

Alphabet 'is planning a 100-year bond': would you back Google for 100 years?Google owner Alphabet is reported to be joining the rare century bond club

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

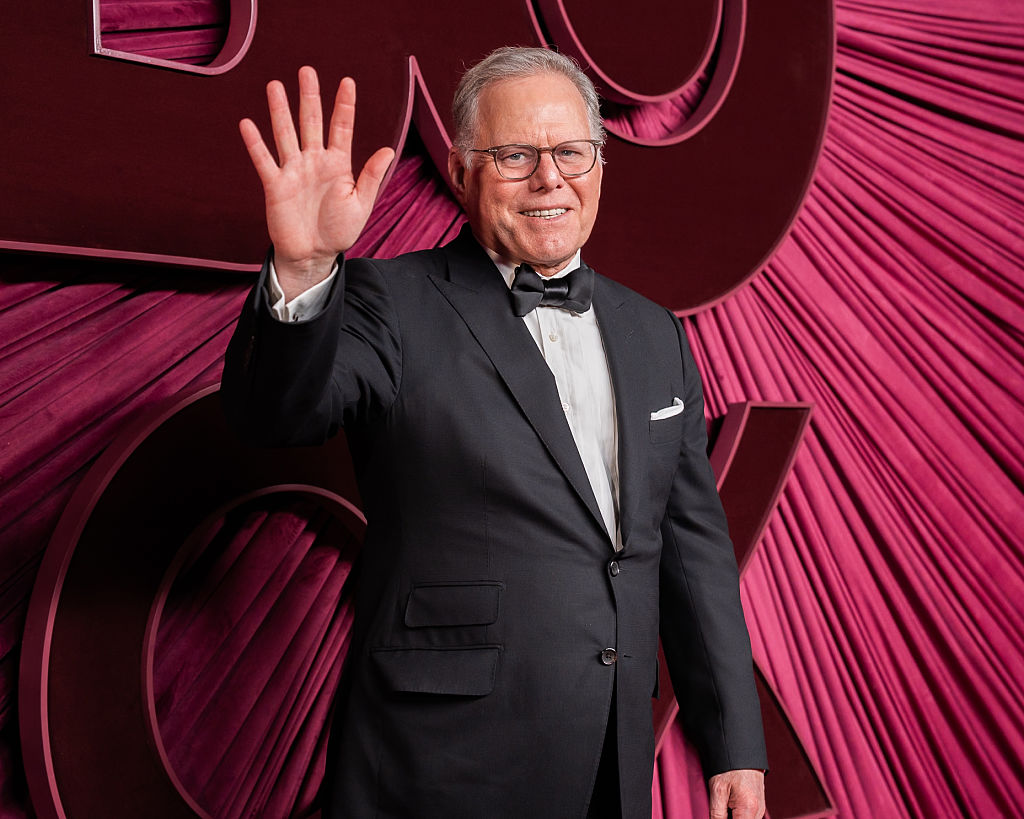

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi

-

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction markets

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction marketsLuana Lopes Lara trained at the Bolshoi, but hung up her ballet shoes when she had the idea of setting up a business in the prediction markets. That paid off