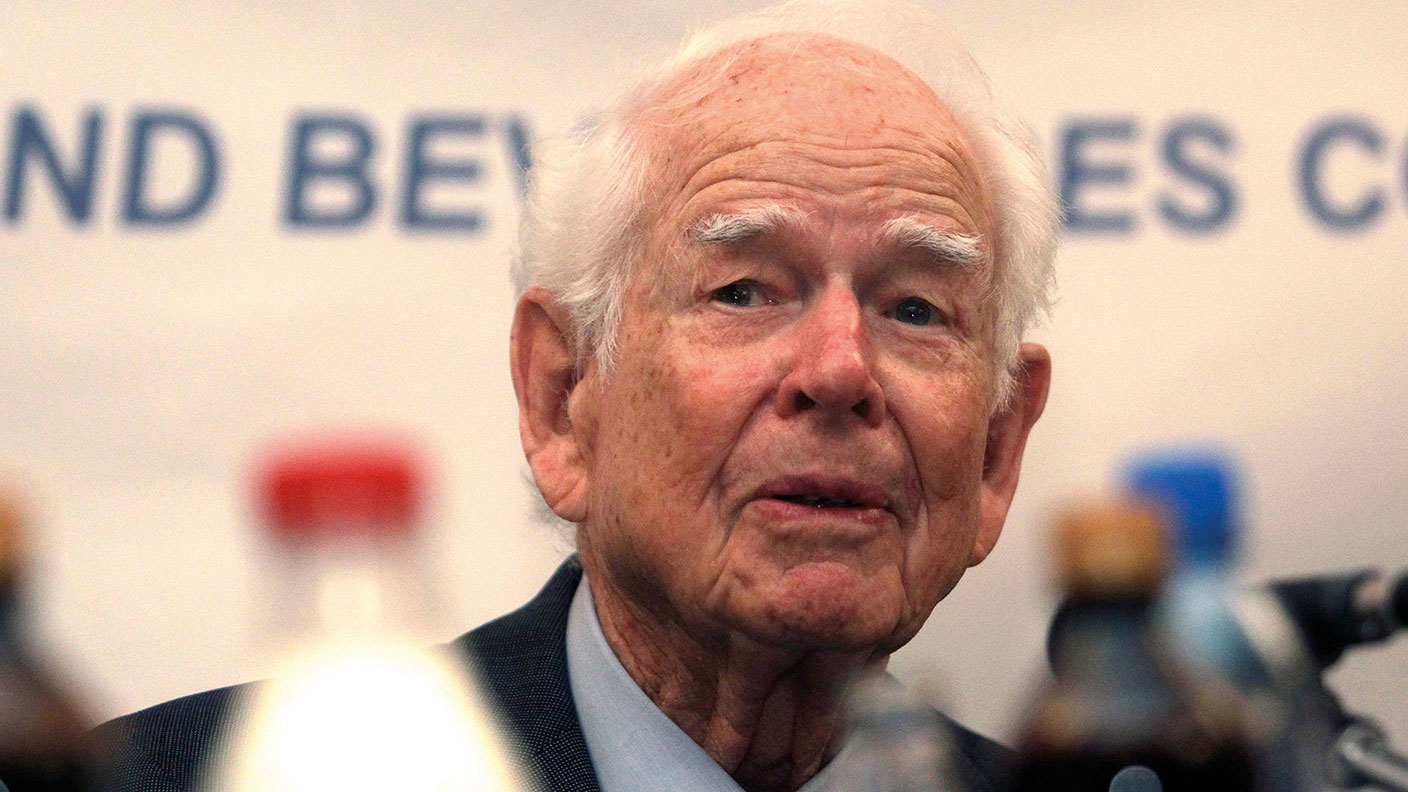

Donald Kendall: helping Pepsi win the cold war

Donald Kendall was there to serve Nikita Khrushchev a Pepsi during a famous cold war détente with Richard Nixon. He went on to become a 20th-century marketing legend.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Donald Kendall, who has died aged 99, was the “stuff of corporate Americana mythology”, says Forbes. Raised on a remote dairy farm in Washington state, he got to college on a football scholarship and earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses while serving in the Navy in World War II, “before landing a job” on Pepsi’s bottling line in 1947. It was the start of a transforming 44-year tenure at the company that saw Kendall emerge as “the man who made PepsiCo PepsiCo” – and a 20th-century marketing legend.

A cultural phenomenon

When Kendall became head of the company, aged 42, in 1963, after rocket-like ascension up the sales ladder, Pepsi “trailed so far behind arch-rival Coca-Cola that the folks in Atlanta didn’t even acknowledge the rivalry”, noted Fortune in 1987. Kendall changed all that – launching a high-profile marketing assault and pursuing it relentlessly until his retirement, by which time sales had grown “nearly 40-fold”, says The Wall Street Journal.

The company followed-up its mid-1960s “Pepsi Generation” campaign, which cast the drink as “the hip upstart cola for young people and Coke as staid and old fashioned”, with the “Pepsi Challenge” taste test. By the 1980s – when Pepsi stunned its bigger rival by signing the era’s biggest music star, Michael Jackson, to promote the brand in a record-setting $5m deal – the “cola wars” had become “a cultural phenomenon”, says The Economist. The battle was a risky gambit, but it paid off in two ways. First it helped fizzy drinks win a greater “share of throat”. Secondly, it produced “the world’s best marketers”. “They brought out the best in us,” Kendall later observed. “If there wasn’t a Coca-Cola, we would have had to invent one, and they would have had to invent Pepsi”.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Nonetheless, the company he built differed substantially from the old rival, says The New York Times. Kendall took greater risks: pushing Pepsi into food production by merging it with crisp maker Frito-Lay in 1965 – and later acquiring (and then spinning off) Kentucky Fried Chicken, Pizza Hut and Taco Bell. He was also a more daring player on the international stage. In 1973, Pepsi’s long Russian campaign finally came good when Kendall signed a ground-breaking manufacturing deal – making Pepsi the first US consumer product to be made and marketed in the Soviet Union (he side-stepped currency exchange complications by accepting payment in Stolichnaya vodka rather than roubles). Later, when the USSR was collapsing, Pepsi struck another coup: negotiating the right to open two-dozen more plants by agreeing to buy 17 Russian submarines and three surplus warships for scrap. “We’re disarming the Soviet Union faster than you are,” he told politicians in Washington.

The end of a more civilised era

“Be sociable, have a Pepsi”, ran an early company slogan. Kendall personified it: combining close friendships with Republican politicians with a progressive outlook that saw PepsiCo become the first US firm to appoint African-Americans to top jobs, staring down a racist campaign against the move to do so. Above all, he was “a company patriot”, painting his home mailbox in Pepsi colours. Kendall’s death coincides with nostalgia for a more civilised political scene, before “mutual contempt… swamped partisan rivalry”, says Edward Luce in the Financial Times. It was still possible, when Barack Obama was rising, to joke about US elections as a choice between “Pepsi and Coke”. Sadly, no longer.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi

-

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction markets

Luana Lopes Lara: The ballerina who made a billion from prediction marketsLuana Lopes Lara trained at the Bolshoi, but hung up her ballet shoes when she had the idea of setting up a business in the prediction markets. That paid off