Great frauds in history: the Pigeon King’s Ponzi scheme

Pigeon-fancier Arlan Galbraith claimed to have created a new breed of elite racing pigeon, but his Ponzi scheme defrauded investors of over £200m.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Arlan Galbraith was born in 1947 in Stouffville, Ontario, in Canada. After dropping out of school he bought a farm with his brother Norman, raising pigs and cattle. By 1980 the brothers declared bankruptcy, forcing Galbraith to turn to farm work to support himself and his family. During this time he acquired a reputation in local pigeon-racing circles, a hobby that he had pursued since he was introduced to the sport as a child. In 2001 he claimed that he had created a new breed of elite pigeon and formed Pigeon King International to exploit it.

What was the scam?

Pigeon King International sold breeding pigeons to investors, particularly Mennonite farmers (because of their reluctance to go to the authorities), in return for promising to buy any offspring at a fixed price for ten years. Since a pigeon typically produces several offspring a year, they would supposedly make their money back in a very short period of time. However, although Galbraith initially claimed the pigeons would be sold on to professional breeders, and later sold as meat, they were instead re-sold to other investors, with the money used to repay the original buyers – turning it into a Ponzi scheme.

What happened next?

The scheme seemed to go well initially, but in 2007 a Mennonite farmer, worried about the impact on the wider farming community, tipped off an online vigilante, who started warning people about the scam. The authorities and many investors initially dismissed the allegations, but when the magazine Better Farming published a detailed exposé in December 2007, the negative publicity drastically reduced the flow of investors. With nowhere to store the tens of thousands of unsold pigeons, and no money to repay investors, Pigeon King declared bankruptcy in 2008. Galbraith was later convicted of fraud in 2012.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

By the time Pigeon King International collapsed, it had obligations of more than C$356m (£205m at current exchange rates) to buy back baby birds, with most investors receiving little or nothing in return. Even if you just count the money paid in, investors suffered net losses amounting to around C$20m (£11.5m). When investing in exotic assets, it’s a good idea to check whether there is enough demand to sustain prices. It’s also a good idea to be sceptical of anyone who insists on unconditional trust, as Galbraith reportedly did, as that usually means that they have something to hide.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?Graduates are complaining about their levels of student debt so should wealthy parents be helping them avoid student loans?

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

The downfall of Peter Mandelson

The downfall of Peter MandelsonPeter Mandelson is used to penning resignation statements, but his latest might well be his last. He might even face time in prison.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

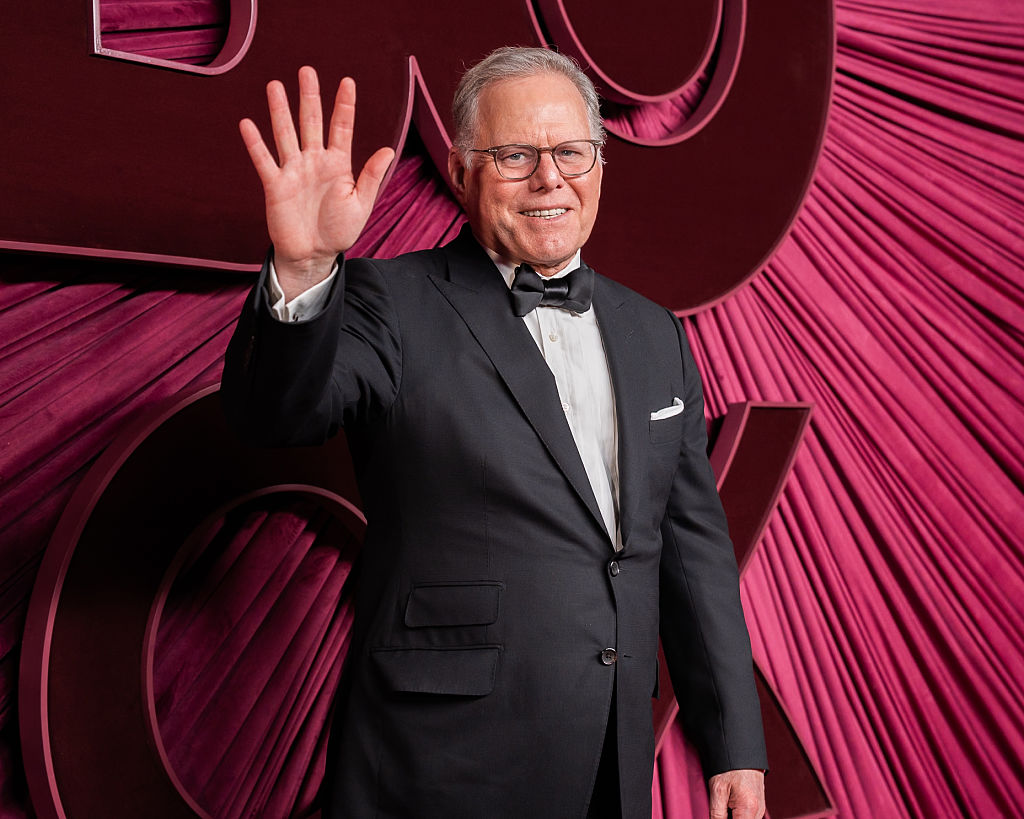

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi