Nick Leeson: the man who broke Barings Bank

"Rogue trader" Nick Leeson’s losses cost his employer, Barings Bank, an estimated £860m, plunging it into bankruptcy.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Nick Leeson was born in Watford in February 1967 and left school after A-Levels to became a clerk in the Lombard Street branch of Coutts bank. By 1987 he had moved to a “back office” (that is, support) role at investment bank Morgan Stanley before taking up a similar position at Barings Bank, where one of his duties involved investigating a case of fraud. By 1992 he had been promoted to the head of Barings Futures Singapore, where he was responsible for “front office” trading decisions as well as providing administrative support.

What was the scam?

The primary task of Barings Futures Singapore was to carry out orders for clients and to make money by exploiting small differences in prices between the Singapore and Japanese markets. In an attempt to boost profits, Leeson started to make proprietary trades with the bank’s own money, focusing mainly on Japanese market index futures. When these trades went badly, Leeson started to hide the mounting losses in a special account designed to correct trading errors. As the losses grew, he increased the size of his bets, hoping that a change in the market would enable him to repay the balance.

What happened next?

The collapse in the Japanese market following the Kobe earthquake in January 1995 led to yet more losses. They eventually grew so large that Leeson realised it was inevitable he would be discovered. He therefore fled Singapore the next month, confessing his crime in a note he left behind. Eventually captured by the authorities in Germany, he sought extradition to the UK, but was eventually sent back to Singapore, where he was sentenced to six and a half years in prison for fraud and forgery, before being released in 1999.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

Leeson’s losses cost Barings an estimated £860m, plunging it into bankruptcy. Despite last-minute attempts to organise a bailout, its main operations were purchased by Dutch bank ING for ��1. This ensured that depositors were protected from losses, but subordinated bondholders in the parent company lost most of their £100m investment. Barings’ management was not involved in Leeson’s fraud, but their complacency and arrogance should have been big red flags for investors. Shortly before the collapse, chairman Peter Baring infamously boasted that it was “not actually terribly difficult to make money in the securities business”.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?Graduates are complaining about their levels of student debt so should wealthy parents be helping them avoid student loans?

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

The downfall of Peter Mandelson

The downfall of Peter MandelsonPeter Mandelson is used to penning resignation statements, but his latest might well be his last. He might even face time in prison.

-

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief clericAyatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us allDolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

-

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz: the richest Welshman to walk the EarthMichael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

-

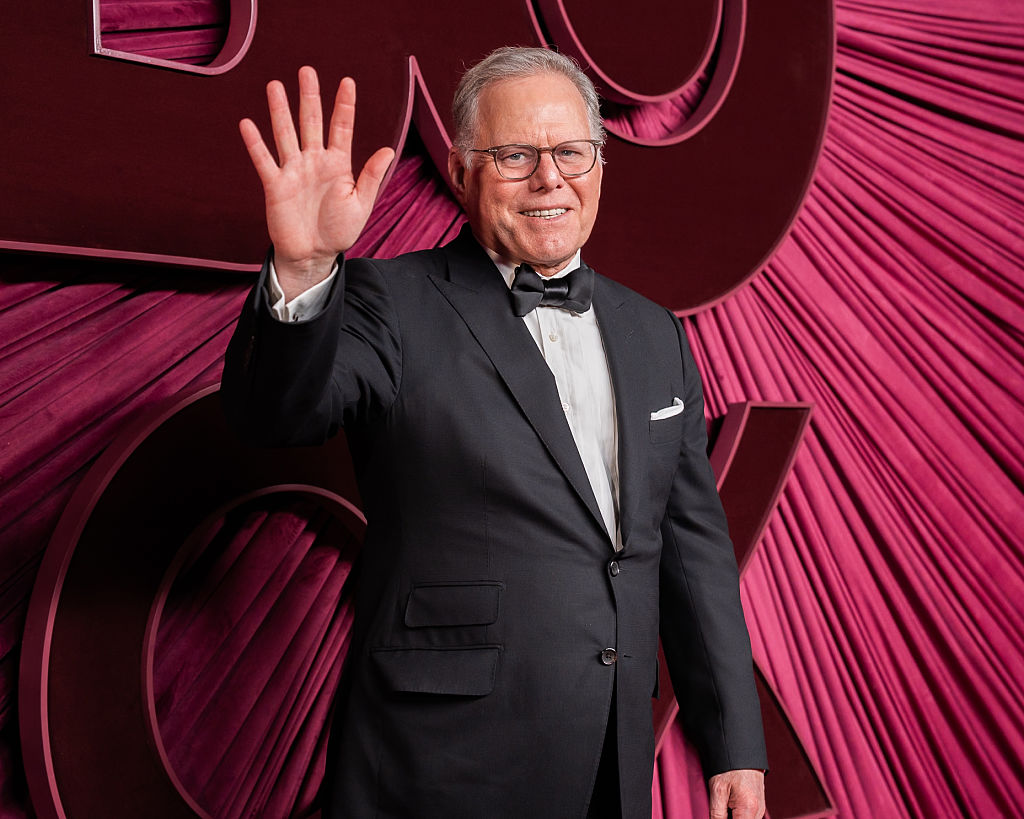

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmakerWarner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

-

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictator

The rise and fall of Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela's ruthless dictatorNicolás Maduro is known for getting what he wants out of any situation. That might be a challenge now

-

The political economy of Clarkson’s Farm

The political economy of Clarkson’s FarmOpinion Clarkson’s Farm is an amusing TV show that proves to be an insightful portrayal of political and economic life, says Stuart Watkins

-

The most influential people of 2025

The most influential people of 2025Here are the most influential people of 2025, from New York's mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani to Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi