Don't bet the farm on shares

With interest rates at record lows, investors may be tempted to pour all their money into stocks. But don’t abandon bonds completely, says Phil Oakley. Here’s why.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

On Monday, I suggested buying index linked gilts as a way of protecting your money from inflation. A number of readers responded that they are too pricey, the RPI to which they are linked is a dodgy measure of inflation, and that buying shares is a much better way to go.

I can understand why people think this, particularly when they see the low returns on offer elsewhere, and when they see high profile names making this case. Just this week, the chief executive of Aberdeen Asset Management said savers should abandon cash and pile into shares as he views the latter as a safer place to be.

However I am not so sure that's right, especially if inflation really takes off.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

How shares can protect you from inflation

The standard argument is that some companies - particularly those that supply essential and branded goods - have what is known as 'pricing power'. Because customers will demand them in good times and bad they have the ability to raise prices to cover the increased costs that come with inflation. This means that there continues to be a healthy gap between money coming in and money going out each year. This ability to keep profits and dividends growing is good news for shareholders.

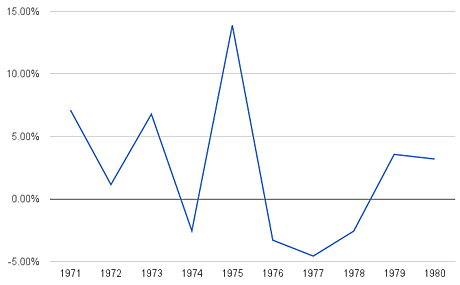

This argument worked pretty well, at least in the long-term, the last time we had steep inflation in the 1970s. But that's in part due to what was happening to wages as this graph shows.

Real wage growth 1971-1980

During that decade, most workers still had more money to spend on company products. This was thanks to the efforts of the likes of the trades unions who were able to keep wages going up faster than the cost of living (creating more inflation in the process). During the 1970s real wages (actual wages less inflation) went up by 23%.

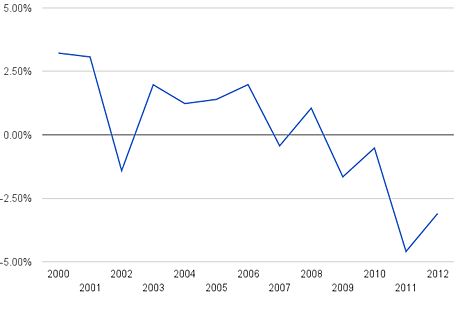

But we live in a different world now. The power of the unions has been quashed and the makeup of the economy has changed. Competition is global and workers have much less bargaining power. Since 2000, real wages in the UK have increased by just 1.9%. While inflation is a lot lower than the 1970s, workers have become steadily poorer in recent times. You have to ask, if inflation goes higher from here will workers in the UK and the rest of the Western world be buying more stuff from companies? Given what's happening to wages, I wouldn't bet on it. Will overseas buyers take up the slack? Who knows?

UK real wage growth 2000-2012

Shares can deliver nasty shocks

Let's assume that companies can protect their profits from inflation. Does that also mean that owning shares has protected people's money from inflation in the past? The answer is yes, but only if you were prepared to be patient. If you needed to turn your shares into cash, you might have been stung by some nasty losses.

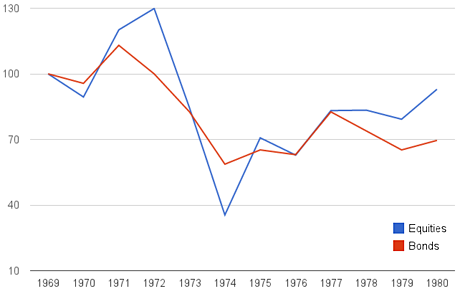

The Barclays Equity Gilt study is packed full of useful information on this. In it, there is a section that shows the performance of a fund of shares and a fund of bonds adjusted for changes in the cost of the living. The chart below shows what happened to the value of £100 invested in UK shares and bonds during the 1970s.

Value of bond and equity funds adjusted for inflation

Source: MoneyWeek/Barclays Equity Gilt Study

As you can see, shares did better than bonds overall. Nonetheless, if you started off with £100 in shares at the end of 1969, you still wouldn't have got your money back in real terms by 1980. Index-linked bonds weren't around in the 1970s, but if they had been they'd probably have done a better job than shares in protecting your money - without delivering the wild ups and downs of the stock market in the meantime.

Risk matters as much as return

This raises a very important point that is easily forgotten as the market rises - shares are risky. The profits of some companies may be able to withstand inflation but that doesn't mean buying their shares is a no brainer. Some simple stock market maths reveals why. Here's the basic formula for stock market returns:

Return from shares = dividend yield + dividend growth + change in price multiple

So let's say you have a share with a dividend yield of 3% with expected growth in dividends of 4% and trading on a price/earnings (p/e)ratio of 12. If the p/e ratio stays the same you should expect to get a return of 7% from owning shares. But what if investors get nervous and are only prepared to payten times earnings for shares? (the p/e of the UK market fell tofour times in 1974) You would get your same 7% less the drop in the p/e of two, which as a percentage of the original p/e of 12 is 16.7%. So that's a negative return of -9.6% (7%-16.7%).

This is the biggest risk that the buyers of shares are now taking. The sort of blue chip shares that are seen as inflation proof are trading on quite punchy valuations. They may continue to do very well, especially given a growing proportion of profits coming from abroad.

But if inflation suddenly spikes up and investors demand higher interest rates to compensate them then the p/e ratios of shares will fall (and with it the value of most financial assets). By buying or owning these types of shares now, you are betting that they will continue to be highly valued by the market. But what happens if one day they are not?

Take Unilever for example a good example of a popular blue chip from the consumer staples sector. I have also highlighted two of its bigger rivals in the table below along with the FTSE 100 index for comparison. Let's say that a market correction saw these shares rated at 17 times forward earnings - which in itself is still a demanding valuation. This derating of the p/e multiple alone would reduce expected returns by nearly 25% (-5.5/22.5 = minus 24.4%).

TABLE {BORDER-BOTTOM: #2b1083 3px solid; BORDER-LEFT: #2b1083 3px solid; FONT: 0.92em/1.23em verdana, arial, sans-serif; BORDER-TOP: #2b1083 3px solid; BORDER-RIGHT: #2b1083 3px solid}TH {TEXT-ALIGN: center; BORDER-LEFT: #a6a6c9 1px solid; PADDING-BOTTOM: 2px; PADDING-LEFT: 1px; PADDING-RIGHT: 1px; BACKGROUND: #2b1083; COLOR: white; FONT-WEIGHT: bold; PADDING-TOP: 2px}TH.first {TEXT-ALIGN: left; BORDER-LEFT: 0px; PADDING-BOTTOM: 2px; PADDING-LEFT: 1px; PADDING-RIGHT: 1px; PADDING-TOP: 2px}TR {BACKGROUND: #fff}TR.alt {BACKGROUND: #f6f5f9}TD {TEXT-ALIGN: center; BORDER-LEFT: #a6a6c9 1px solid; PADDING-BOTTOM: 2px; PADDING-LEFT: 1px; PADDING-RIGHT: 1px; COLOR: #000; PADDING-TOP: 2px}TD.alt {BACKGROUND-COLOR: #f6f5f9}TD.bold {FONT-WEIGHT: bold}TH.date {FONT-SIZE: 0.7em}TD.first {TEXT-ALIGN: left}TD.left {TEXT-ALIGN: left}TD.bleft {TEXT-ALIGN: left; FONT-WEIGHT: bold}

| Diageo | LSE:DGE | 2016 | 2.40% | 19.6 | 8.70% |

| Reckitt Benckiser | LSE:RB | 4755 | 2.90% | 18 | 6.70% |

| Unilever | LSE:ULVR | 2736 | 2.90% | 22.5 | 9.30% |

| FTSE 100 | Row 3 - Cell 1 | 6355 | 4.20% | 10.6 | 11% |

Overall I agree that equities are one of the least worst places to put your money at the moment. But I don't advocate anything like a wholesale switch. I shall continue to hold some index-linked bonds in my portfolio too and would urge you to do the same.

This article is taken from the free investment email Money Morning. Sign up to Money Morning here .

Our recommended articles for today

It's all over for bank stocks

Bank profits staged a remarkable recovery in 2012, and stocks rose handsomely. But the rise was all down to smoke and mirrors, says Bengt Saelensminde. There is plenty more trouble ahead for the banks.

Flatlining Britain needs a short, sharp shock

SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Ireland and Latvia have proven that austerity can work if the cuts are made deep and fast, says Matthew Lynn. That has to be preferable to Britain's never-ending stagnation.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Phil spent 13 years as an investment analyst for both stockbroking and fund management companies.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how