Explorers strike black gold

As the price of oil spiked two years ago, the industry began scouring remote reaches of the ocean to find new reserves. and now, oil explorers have recently made some significant discoveries. Eoin Gleeson investigates, and picks the best ways to invest in the new oil boom.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

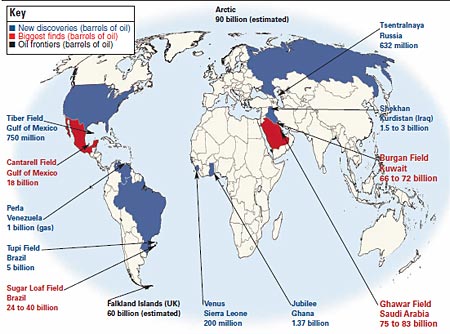

For an industry that is meant to be downing tools, oil explorers have found a hell of a lot of the stuff recently. First Iran strikes 8.8 billion barrels. Then BP uncovers a "giant" discovery in the Gulf of Mexico. And then Tullow Oil announces it has found a whole new oil basin, stretching 1,100km from the coast of Ghana to Sierra Leone. Have they been hiding this stuff from us?

Not at all. Oil experts have been factoring new discoveries like these into estimates of the world's oil reserves for some time, says Carola Hoyos in the FT. As the price of oil spiked two years ago, the industry began scouring remote reaches of the ocean to find new reserves. But firms quickly found their equipment wasn't up to the job. So they ploughed a fortune into developing drills and seismic equipment that could sound out fields deep beneath the seabed. Now those innovations are starting to pay off. Slowly, a picture has began to emerge of vast, untapped reserves miles under the oceans. Anticipating this, geologists have been adding allowances for undiscovered deepwater oil into their forecasts of future supply.

So are our energy woes over? Absolutely not. Large offshore discoveries like this are incredibly expensive to develop. BP had to drill more than 35,000 feet beneath the Gulf of Mexico in order to strike oil. And recovery rates could be as low as 5%-15% of oil in place, perhaps yielding just 150 million barrels of oil from its discovery, says Keith Johnson in The Wall Street Journal. To put these finds in context, we need to find 45 million new barrels a day from 2030 to satisfy demand, according to the International Energy Agency. These new discoveries will not plug the gap.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The growing importance of deepwater finds means that oil explorers are going to have to work harder on new discoveries in future. They'll need a wealth of seismic surveying to scope out those reserves. Deepwater oil exploration begins with a fleet of seismic vessels dragging sonar equipment thousands of feet below the ocean surface to bounce waves beneath the bedrock. Each layer of sedimentary rock reflects different parts of the sound waves back to shipboard receptors. Huge amounts of seismic data will be collated into detailed 3D maps of the oil-filled caverns so oil experts can pinpoint the best place to sink a drill. For BP, it was a case of how best to place an $80m-$100m well the size of a dinner plate on the seafloor

That work came to an abrupt end during the recession. The oil price sank and investment in expensive seismic surveying fell with it. Surveys were down 30% in the first half of this year, according to Danske analysts. In past downturns, seismic specialists have ploughed ahead with surveys on their own account, to prevent vessels going idle. Not this time. Ships are being called back and at least eight of the 28 new vessels scheduled for 2011 are at risk of being cancelled. The industry is suffering from serious overcapacity, creating huge downward pressure on contract margins.

But demand for contract work is picking up again. And providers are united in their focus on reducing existing capacity: an estimated 58 vessels will enter the market this year, while 73 will be removed. Once the oil price rises again, the search for remote oil reserves will drive a sharp rebound in surveys and in these firms' prospects (see below).

The best bet in the sector

Seismic groups were left for dead when oil collapsed. In August last year, we tipped CGG Veritas (NYSE: CGV), believing that the group's ownership of leading seismic-equipment manufacturer, Sercel, would see it through the recession. But the collapse of Lehman Brothers a few weeks later made what had already happened look trivial in comparison. CGG Veritas is down a 49% since then, in an environment where day rates have fallen 30%-50% for many of the modern vessels.

The firm is doing more than any of its peers to streamline and modernise its fleet, says analysts at Danske; it's currently making plans to cut its fleet from 27 to 20 vessels. But competitor Petroleum Geo-Services (Oslo: PGS, NYSE: PGSVY) might be a better candidate for a quick recovery. PetroleumGeo-Services has a more modern fleet. With 13 vessels at its disposal, having recently cancelled its new builds, it is also less afflicted by overcapacity than CGG Veritas.

Petroleum Geo-Services has been reducing its leverage, with net debt to equity falling from 1 to 0.5 times. Revenue is partly protected by a $743m order book, which in June grew for the first time since the Lehman collapse as multiclient surveys picked up. Contract margins are still declining and the firm estimates another 10% of global capacity must be removed to balance the market, but cost-cutting is helping to repair the damage. With the market pricing in a lost year in 2010, the grouplooks a cheap recovery play on a forward p/e of 11.

How to play the finds

Where will the oil industry find the 45 million extra barrels of oil a day it needs to secure by 2030? Well, after surveying 25 oil-bearing regions north of the Arctic Circle, Donald Gautier of the United States Geological Survey is convinced there could be up to 90 billion barrels of undiscovered oil in the Arctic basin. But it will be a long time before it's economical to drill in those waters, Gautier told ABC News this week.

Things are progressing much more quickly in the Falklands. In July, we noted how British firm Rockhopper Exploration had struck a natural gas deposit that it thought could be as big as 1.6 trillion cubic feet. And major energy groups had stepped in with financing for small explorers to complete seismic reviews and help secure scarce rigs. Last week, Desire Petroleum managedto get its hands on a rig. It aims to start drilling four wells in the North Falkland Basin as early as February. Our tip Falkland Oil and Gas (Aim: FOGL) has jumped in sympathy it's up 47% since July. If Desire strikes oil, then there is a good chance that Falkland Oil and Gas will too, says Kevin Goldstein-Jackson in the FT perhaps hiring the same oil rig.

If you're willing to risk incurring the wrath of the Baghdad government, then Kurdistan is another exciting oil frontier, says Tom Bulford in Red Hot Penny Shares. Oil junior Gulf Keystone struck an estimated 1.5 billion to three billion reserve last year. And Sterling Energy (LSE: SEY) is expected to start drilling by the end of the year. Sterling collapsed earlier this year on concerns about its debt levels, but it has attracted new financial backers and announced a placing of extra shares to raise £62.5m in August. If it hits oil, it will go from 3.7p to 10p, says Bulford.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Eoin came to MoneyWeek in 2006 having graduated with a MLitt in economics from Trinity College, Dublin. He taught economic history for two years at Trinity, while researching a thesis on how herd behaviour destroys financial markets.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge