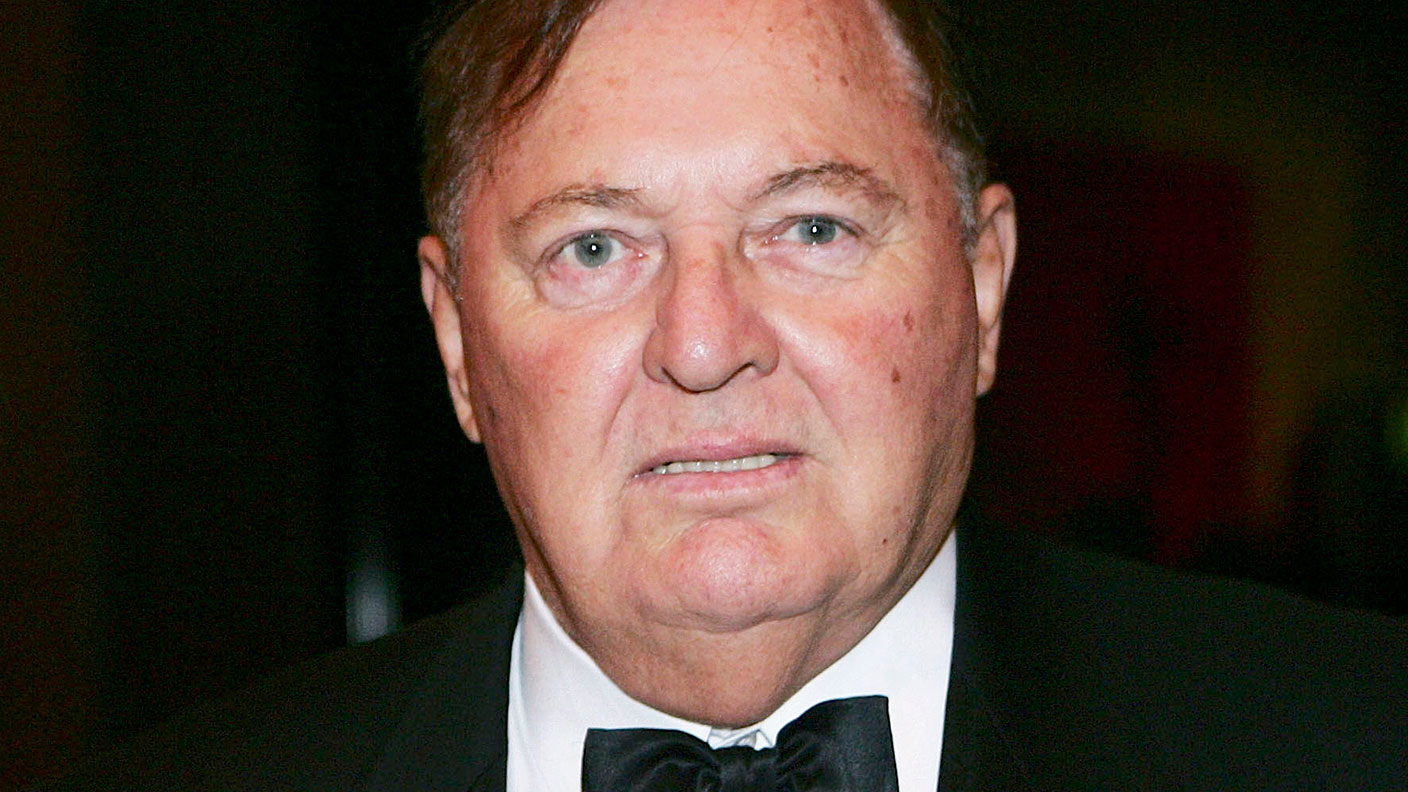

Great frauds in history: Byrraju Ramalinga Raju and Satyam

Byrraju Ramalinga Raju boosted the share price of his company by inflating profits, cash flows and assets, creating false bank statements, customer invoices and even fake salary accounts.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Byrraju Ramalinga Raju was born in Bhimavaramin southeast India and received a degree in commerce before going on to do an MBA at Ohio University. He then went back to India and started various industrial, real-estate and construction firms, with mixed results. In 1987 he set up Satyam Computer Services, one of India's first outsourcing firms, taking it public in 1992. By the start of 2009 Satyam was India's fourth-largest IT firm and was providing IT and accounting services for more than 600 large companies, including international conglomerates General Electric, Nestl, and BP.

What was the scam?

From 2001, in order to boost Satyam's share price, Raju began working with key executives, including those within the company's internal audit team, to systematically inflate profits, cash flows and assets. Raju and his team did this by creating false bank statements, customer invoices and even fake salary accounts. The company also used forged board resolutions to obtain loans that were never declared on the balance sheet, using the money to keep the scam going. By September 2008, reported sales were 25% higher than actual sales, while assets were overstated by $1.47bn.

What happened next?

In December 2008 the company announced it was buying an infrastructure company owned by Raju's sons. The deal was approved by the board, but it generated a massive backlash from shareholders, along with the resignation of all the independent directors. Raju was forced to confess publicly that he had been systematically defrauding investors, prompting the company's share price to collapse. Raju was arrested along with two other company executives. He was convicted of fraud in 2015 and sentenced to seven years in prison, but he remains out on bail.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

Due to Satyam's economic importance, the Indian government stepped in and organised a takeover by Tech Mahindra, but shareholders who had bought just before Raju's fraud came to light would lose two-thirds of their investment. Between 2001 and 2008, Raju gradually dumped shares onto the market, reducing his stake from 25% to only 3.6%. Selling on such a scale by close insiders, especially the chief executive, can be a sign that things are going wrong, or that they lack confidence in their firm's future.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Do you face ‘double whammy’ inheritance tax blow? How to lessen the impact

Do you face ‘double whammy’ inheritance tax blow? How to lessen the impactFrozen tax thresholds and pensions falling within the scope of inheritance tax will drag thousands more estates into losing their residence nil-rate band, analysis suggests

-

Has the market misjudged Relx?

Has the market misjudged Relx?Relx shares fell on fears that AI was about to eat its lunch, but the firm remains well placed to thrive

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.