Great frauds in history: Victor Jacobowitz’s phony account

Victor Jacobowitz fiddled the inventory records of his health and beauty products business and defrauded investors out of €177m.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

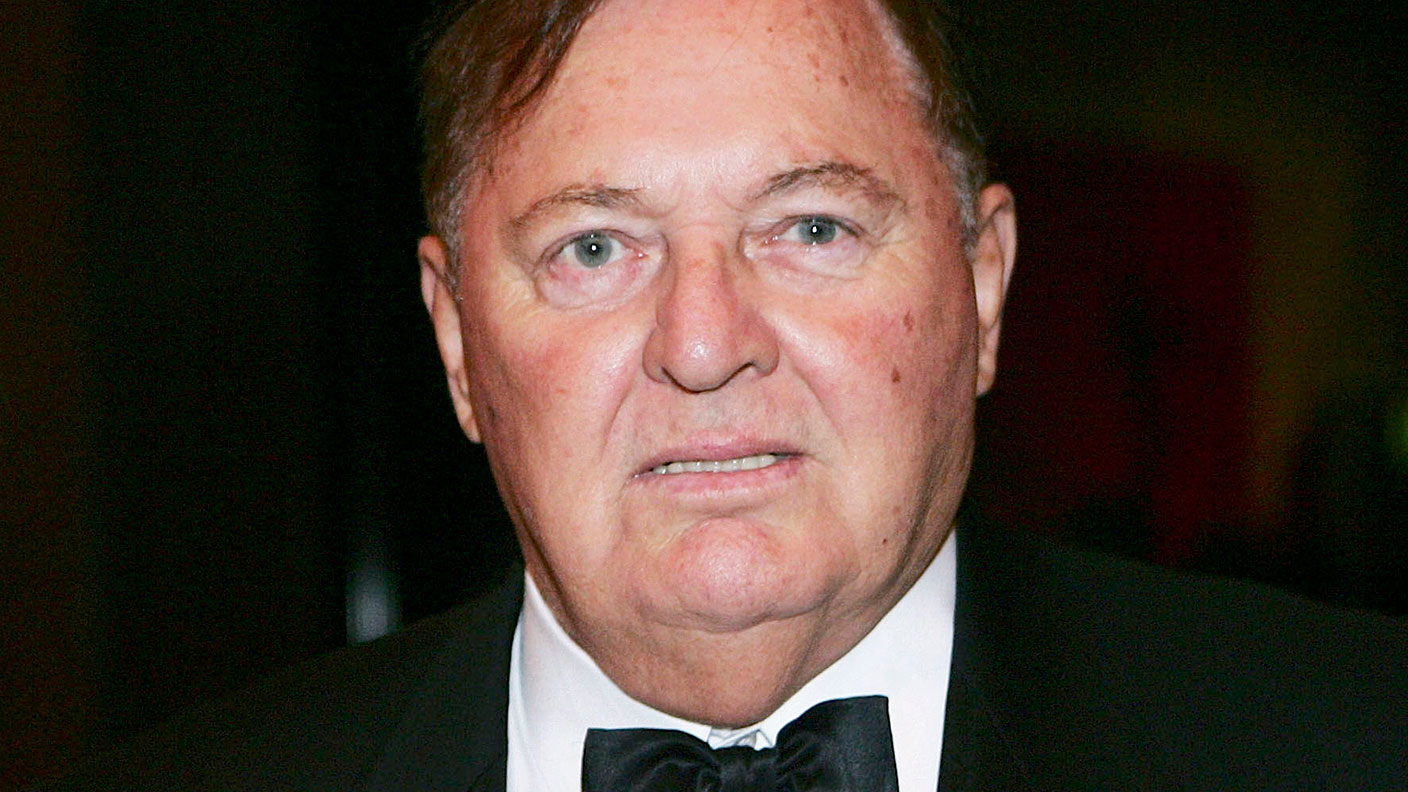

Victor Jacobowitz (pictured, centre) was born in New York in 1932. He took over Allou Healthcare with two of his sons, Herman and Jacob, in 1985, before floating it on the stock exchange four years later. In the three decades following the purchase, the Jacobowitzes built it up into one of the largest distributors of health and beauty products in the United States, with a particular focus on perfume. By 2002, Allou reported net income of $6.6m on sales of $564m and employed more than 300 people, with warehouses in New York, Florida and California.

What was the scam?

From the 1990s onward, Allou had an agreement with lenders that allowed it to borrow up to 60% of its inventory and 80% of its invoices. This enabled it to start systematically inflating both its sales and its inventory by engaging in phoney transactions with independent companies owned by the Jacobowitz family, in order to borrow increasing amounts of money. Most of this money was used to aid the fraud, but some of it was skimmed. By 2002 a third of reported sales were fraudulent. To keep investors satisfied, accounts were also falsified to give the impression that the company was profitable.

What happened next?

By 2002 the gap between reported and actual inventory had become too great to hide. The cost of the accumulated borrowing also meant that the company was hopelessly insolvent. The family decided to burn down the main warehouse in New York and then claim on the insurance. However, the subsequent fire was ruled to have been started deliberately and when they attempted to bribe the fire marshalls, the police were notified. By 2003 the firm was declared bankrupt and several people involved in the fraud (including Herman and Jacob) were jailed.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

The courts attempted to seize the defendants' property to repay Allou's debts, but lenders still lost an estimated $177m. Its shareholders ended up wiped out. In order to prevent its scam from being discovered, Allou regularly changed its auditors, with three (Mayer Rispler, Arthur Andersen and KPMG) taking the job over three years. Companies do occasionally switch auditors from time to time for various legitimate reasons, but several changes in such a short period are definitely a red flag that things are not what they seem.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.