Commodities are dirt cheap – but is it time to buy?

Commodities are staggeringly cheap, says Dominic Frisby. By some measures, they are twice as cheap as they were at the turn of the century. But does that mean it's time to buy?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

I wanted to pick up today on a chart I posted in last week's Money Morning.

I think the message it is sending out could be very significant, and it is something we should be thinking about as we allocate our portfolios.

In today's Money Morning, we are talking oil and gas, copper and zinc, cotton and coffee, wheat and corn commodities.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Productivity equals progress

We might moan, but sometimes it's important to recognise just how lucky we are to be alive in 2019. An ordinary person today enjoys a standard of living better than at any time in human history.

Even kings in the past did not enjoy much of what we take for granted. Electricity, running water, central heating, food from all over the world (more than we can eat), fruit out of season, planes, trains and automobiles, and a phone that can do a million different things.

We also enjoy prices which are, broadly speaking (and adjusted for inflation) as cheap as they've ever been. That's because humans have got better at growing stuff, they've got better at mining stuff, they've got better producing stuff. That's progress.

Progress means that there will always be a downward pressure on commodities prices, whether food, metal or fuel. Improved productivity pushes prices down. However, sometimes that downward pressure is so great, that many businesses stop producing altogether mines go bust, or farms change their business models and that can lead eventually to a shortage of said commodity.

That shortage then forces prices higher, so more people then look to start producing that commodity, until eventually the increased supply forces prices back down again. This process can sometimes take several years.

In the 1990s commodities prices were forced lower and lower. Then, at about the same time as prices reached rock bottom, China and India appeared on the scene with their new and ambitious middle classes, expecting the same lifestyle that Western middle classes take for granted, and suddenly commodities demand went through the roof. An epic ten-year bull market followed.

Things got excessive, prices peaked and they've spent the most part of the 2010s in decline. But prices have not hit rock bottom. Brent crude is still $63 a barrel, not sub-$10 as it was in 1999. Copper is $2.60 per pound, not $0.60. Coffee is $1 not $0.40 and so on.

This may surprise you, but commodities are staggeringly cheap

Yet that's because these prices have been masked by inflation. If you look at commodities on a relative basis, you realise just how cheap they are.

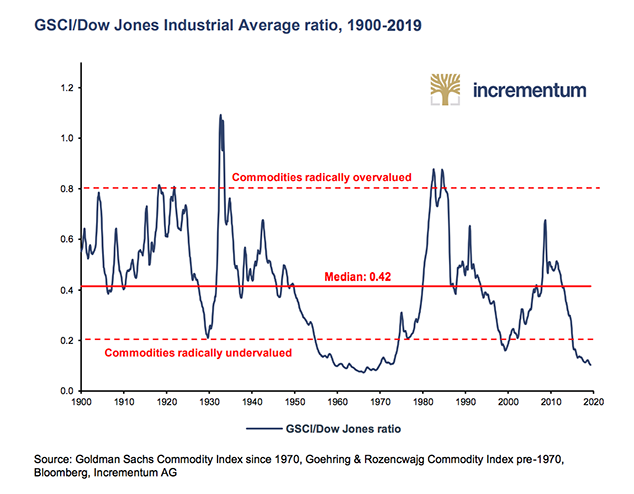

Here we see the ratio between commodities and stocks, specifically between the Goldman Sachs Commodities Index and the Dow Jones index. The chart comes from Incrementum AG's annual research note, In Gold We Trust.

Today commodities are, relative to stocks, cheaper than they were at the turn of the century. The last time they were this cheap was in the 1960s and never before in the 20th century. I think that's a staggering fact.

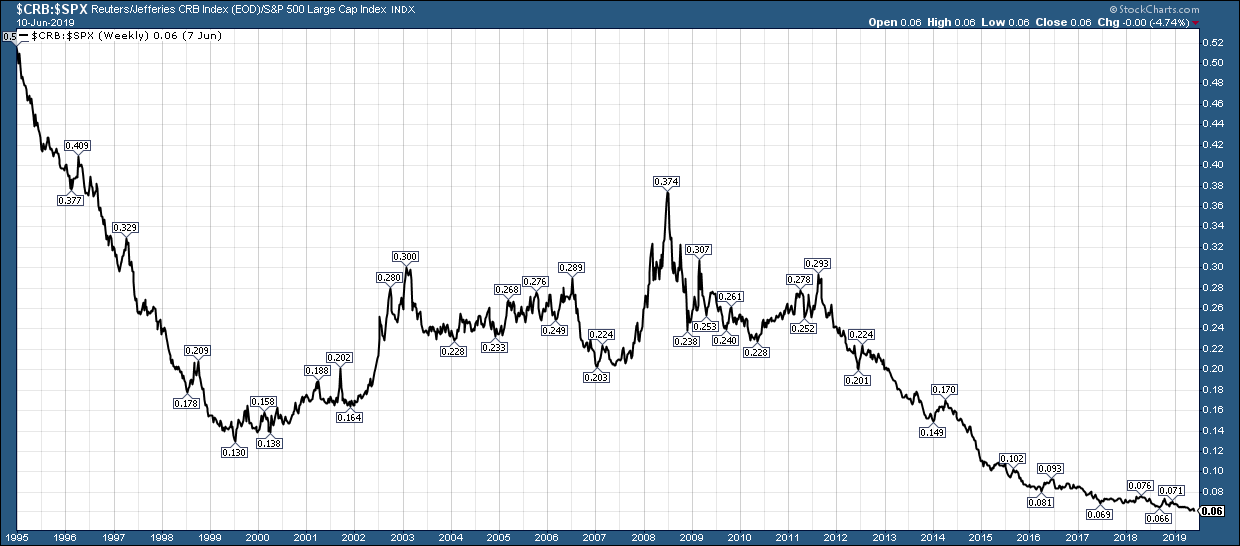

Next we see commodities prices in the form of the CRB Index versus the S&P 500 since 1995. According to this measure, commodities are half the price they were in 2000 and remember what an epic buying opportunity that was.

When the black line is falling, commodities are falling in price relative to stocks and vice versa.

It's inevitable that this ratio is going to creep lower and lower over time, because of the dynamic of progress and productivity that I described above. Companies may grow more and more valuable, but productivity is such that the cost of essential commodities falls.

In the 19th century, industry became mightier than agriculture. Today, tech is growing bigger than industry. The digital economy is where the money is. So why don't we compare the Nasdaq to the CRB? Here it is since 1986 (this is a log chart)

In the 1980s the ratio was 1:1. Now it is 0.02:1. The declines are extraordinary. Remember how overvalued tech stocks were at the peak of the dotcom double? Well commodities are more than twice as cheap today as they were back then.

If you want to bet against human ingenuity, you have to get your timing right

It's just extraordinary how the economy has shifted away from real and into digital. It's because of the scalability of digital code can be instantly and infinitely replicated. An app can be downloaded a billion times; making a billion cars is a rather different undertaking.

But the gearing of US stockmarkets to tech stocks, whereas British and European markets have stuck with traditional industry, is another reason the US has so outperformed Europe.

The moral of the tale is don't invest in stuff, invest in tech.

And yet investing in stuff can make you a fortune just ask Jim Rogers or Alan Bond. Pick a winner in mining and you can easily make ten times your money. Commodities bull markets do happen.

There have been two major bull markets in my lifetime in the 1970s and in the 2000s. But there was a 20-year gap between them. Another 20-year gap would take us to around 2030!

On a relative basis we are at levels from which a rally could be staged. There is sufficient blood on the streets certainly in mining. So I'm comfortable with some exposure to the sector right now.

But when investing in this sector it is as well to be aware that, in a way, investing in commodities is almost like betting against human progress. And that has never been a very wise bet.

This dynamic applies especially to grains and soft commodities, which can be grown less so to oil and metals, whose supply is finite. But even so, some food for thought.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how