Uranium looks a good long-term bet – here’s how to play it

Uranium is viewed with suspicion by the public, but it’s an essential part of global energy production – and we are set for a shortage. Dominic Frisby explains how to invest.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Back in July, I wrote an article for MoneyWeek magazine about uranium.

"The most hated metal in the world is due a comeback" ran the title.

Today we revisit uranium and consider some of its prospects from here.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The winter seems cruel for nuclear fuel

Since that article uranium has had something of a comeback, and, subsequent to that, a pullback. U3O8 was trading at $22 per pound. It had a nice rally to $29/lb in December, since when it has rolled over slightly and today we sit at $27/lb.

The five-year low came in 2016 at $18/lb. The five-year high was back in 2014 at $43.

Below, for your information, is a five-year chart of the uranium price. What struck me as I was perusing the price action is that uranium has tended to make a high either just before or just after the turn of the year and then sells off through the winter (see the red arrows in the chart below). You never know if these kind of seasonal patterns are just a coincidence, but this year we are following that trend, and the price seems to be rolling over.

On the evidence of this, now is a better time to be watching than buying. 2014, 2017 and 2018 all suggest we should be looking to buy in the late April to June timeframe.

What is encouraging about this chart and it is the point I was about to make about it before I got sidetracked by the seasonal patterns is that over the past two-and-a-bit years, we do have something of an uptrend. The 2017 lows were higher than the 2016 lows. The 2018 lows were higher than the 2017.

All in all this would suggest perhaps that we drift lower over the next month or three, perhaps to the $25 area, before things get going again.

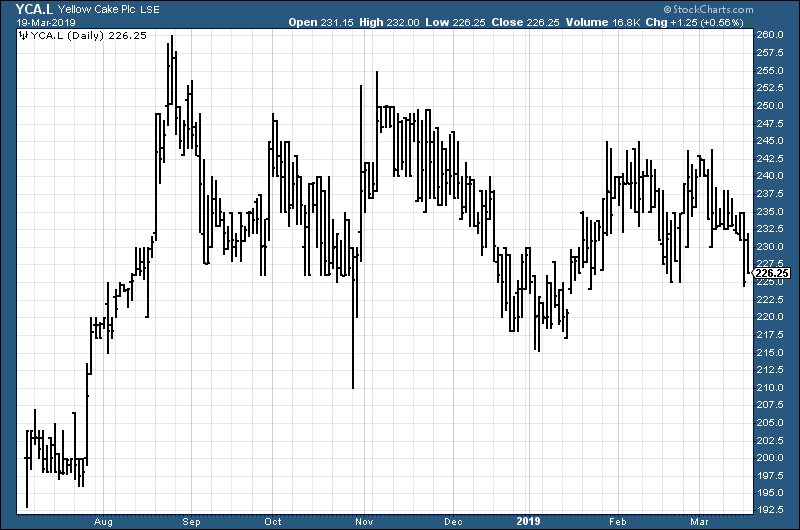

The July piece I wrote for MoneyWeek coincided with the launch of Yellow Cake (LSE: YCA). Effectively, this is an exchange-traded fund (ETF) which investors can buy through their brokers and gain direct exposure to the uranium price. You can't, of course, buy and hold uranium at home.

The reason you might want to buy the metal directly is so that you don't have to take on the individual company risk of buying a miner. (Building a mine, especially a uranium mine, is a lengthy and expensive process and there is a lot that can go wrong, as a company attempts to develop their property and bring it into production.)

Yellow Cake raised £150m at IPO no small beer. Its strategy is about as simple as it gets. Peter Bacchus, who is behind the deal, thinks uranium is "structurally mispriced". He has bought lots and is now stockpiling it in anticipation that, sooner or later, its price will go up.

Below we see the price action of Yellow Cake since its inception.

Since September it has broadly been in a range between about 255p and 215p, with the slightest of downtrends.

Uranium's biggest problem

The biggest problem uranium has is public perception. Rightly or wrongly, the public almost the world over remain far from convinced about nuclear power. Nuclear power may or not be the cleanest, most efficient way to mass produce electricity, but the general public still don't like it.

In the 2000s, when uranium had its mania, the public might have been gradually coming round to the idea, especially as the "Peak Oil" narrative was so strong, but since the 2011 Fukushima disaster in Japan, attitudes have changed.

Before the disaster, 30% of Japanese electrical power was generated by nuclear reactors, with plans for it to rise to 40%. Today Japan has 42 operable reactors and just nine of them are functioning. Germany was another country that changed its strategy after Fukushima. Before the disaster, 25% of its electricity came from nuclear power. Today that figure is 12%. German public opinion is, broadly speaking, opposed.

Adherents of nuclear power will tell you it is cheaper, cleaner and far less of a threat to human life whether by disaster, pollution or otherwise than fossil fuel alternatives, but I'm not sure that matters while the general public hold their current views.

Adherents will also tell you these views are entrenched in the public because of deliberate campaigns driven by the oil industry in the 1970s, to smear nuclear power in order to protect their own business interests. Right or wrong, true or false, the result is that the public still don't like nuclear.

If their energy costs were two or three times higher, and there was a successful pro-nuclear campaign, those views might change, but for now they are entrenched, and there will always be that underlying fear of radiation, sickness and all the rest of it.

Public perception is the biggest battle nuclear power has to face.

The reality of supply and demand

Currently, we need around 80 million tonnes a year of uranium. This is just about being met by current mine supply and stockpiles. New reactors under construction mean we will soon need another 12 or so million tonnes a year; reactors on order mean a further 32 million tonnes. Meanwhile, stockpiles are dwindling and several large mines have suspended operations.

On the other hand, several other large mines should soon be coming into production, which will offset some but not all of the lost supply Husab in Namibia; Mulga Rock (potentially) and Wiluna in Australia; Arrow Canyon in North America (which has environmental protest problems); and Salamanca in Spain.

Meanwhile the shortfall between demand and new mine supply that has been met by existing stockpiles is also in jeopardy as stockpiles are low.

So the stage is very definitely set for a shortage, as Bacchus foresees. But, at the same time, if future supply was really as constrained as some suggest, the price would be a lot higher than it is.

Overall, I suspect that this may all take a long time to play out, but the fundamentals are certainly there for the price to go higher. My view is that uranium bought with a timeframe of at least five years will pay dividends.

It's one of those planes that will suddenly take off so it makes sense to book your seat while it's still cheap whether you buy the metal or one of the miners. Everyone should have some uranium exposure in their portfolio.

But it also makes sense not to rush, particularly given the seasonal patterns I observed above. Have your seat booked by June, then buckle up for a long, slow, turbulent ascent.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how