Investors are finally losing interest in UK housing

House prices are on the way down. It looks as though people are starting to lose their faith in property as an investment. John Stepek explains what’s going on.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The great UK house-price slowdown continues.

This morning, Nationwide reported that annual house-price growth fell to its lowest level in more than five years last month.

I may be speaking too soon, but it looks as though people might be starting to lose their faith in "bricks'n'mortar".

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What the change in housing transactions tells us about the market

Last month, UK house prices rose by a mere 1.6% year-on-year. Regardless of which inflation measure you use retail prices, consumer prices, wage inflation that's a proper, real-terms (after inflation), drop in house prices. Relative to the cost of living, house prices are definitely falling.

House prices haven't been this sluggish since May 2013, according to Nationwide. And back then, prices were about to pick up. This time round, they're on the way down.

So what's going on? One thing that house prices don't like is rising interest rates and tighter credit conditions. However, while certain areas have tightened up, it's hard to argue that mortgage availability or cost has changed dramatically.

You can certainly argue that Brexit might have something to do with it. I'm still sceptical, but people might want to delay purchases until next year's deal deadline is passed. Yet, if that's your plan, you could be waiting a long time unlike the millennium bug, the deadline for Brexit to be a done deal is a moveable feast. So it might have an impact at the edges but I'm not sure it's as great as some might wish.

Instead, I think it's because the UK housing market is finally losing its appeal as a core investment asset (despite the endless swathes of celebs who still opt for property over pensions when interviewed in the Sunday newspaper money sections).

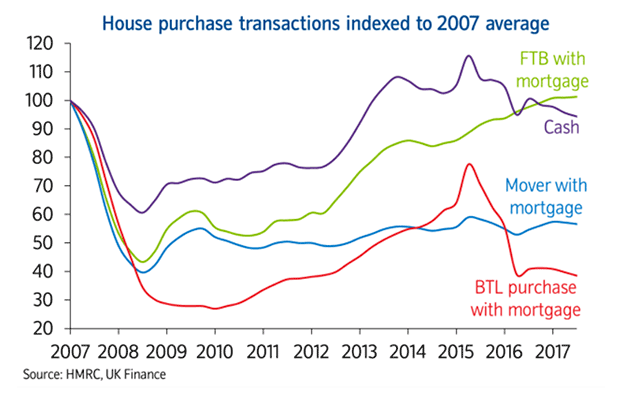

Nationwide published an interesting chart in today's press release, which I've reprinted below. It looks at how the mix of buyers has changed over the last 10 years or so. And I think it demonstrates what's really going on here.

The chart looks at how the number of deals done by first-time buyers, cash buyers, home movers (with mortgages), and buy-to-let investors has changed, relative to their pre-financial crisis levels. Transactions in general, of course, cratered after the financial crisis. They've all recovered since then, though not all have regained their pre-financial crisis peaks.

Cash buyers and would-be landlords are dropping out of the housing market

So what can we tell from the change in the mix? One thing stands out quite clearly to me the housing market is losing its appeal to investors.

First, take a look at cash transactions (the purple line). These recovered most rapidly post-crisis. The growth in cash transactions, says Nationwide, is partly due to our ageing population. Today, more home-movers own their homes outright and so transact in cash when they move. That could go some way to explaining why the proportion of transactions by home-movers with mortgages (in blue) has been relatively flat since rebounding from its absolute nadir in 2008.

However, a far bigger driver is the investment sector. Buy-to-let landlords often buy homes for cash, as do overseas investors. One reason cash deals recovered so quickly is because those with cash at the ready were able to jump in and buy at a time when banks weren't lending. And those with cash in other currencies were able to profit from the 25% crash in sterling after 2008.

What's interesting here is that cash deals spike in 2015. They then start to drop off pretty sharply. Simply reading off the chart, cash deals now look as though they've fallen back to 2013 levels or so.

Now look at the red line landlords buying with mortgages. Transactions take longer to recover after the crash (because they couldn't get loans), but then race up sharply. Then there's a big spike also in 2015 and then they fall off a cliff.

What happened in 2015? That was the year buy-to-let was targeted hard by then-chancellor George Osborne. First, his landlord tax reforms were announced, making it far less attractive to purchase using borrowed money. Then in November the same year, the stamp-duty surcharge on second homes was announced. That led to a rush to buy before the surcharge kicked in, in April 2016.

Since then, transactions in these sectors have collapsed. And while first-time buyer numbers have continued to recover (thanks partly to Help-to-Buy) in the meantime, that's a different market.

Indeed, you have to wonder where house prices would be now if it wasn't for the fact that the Help-to-Fund-Housebuilder-Bosses'-Big-Bonuses scheme means that many of those first-timers are paying over-inflated prices for the new-builds they are naively purchasing.

Overall with the exception of ripped-off first-time buyers this is broadly good news. It's not efficient for an economy and no fun for the humans who comprise it if a large proportion of people are spending huge and rising chunks of their income simply keeping a roof over their heads, or feel unable to move or change job easily because they are so terrified of what might happen if they can't maintain their mortgage payments.

We wanted house prices to be flat or gently falling, and that's what we've got. Long may it continue. Is it likely to? The experts at our most recent property roundtable, published in MoneyWeek magazine in September, were not entirely optimistic on that front but there's at least a chance. You can read their views here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how