Why “peak” arguments are always wrong

First we had “peak oil”, now electric cars will bring about “peak lithium”. But don’t worry, says John Stepek, “peak” arguments are always wrong. Here’s why.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

A charismatic if somewhat eccentric chap comes along, repackaging the idea of an electric car into a sleek Apple-esque exterior, and at just the right time in the oil production cycle.

Everyone with a bit of disposable income and even a minor fondness for gadgets thinks: "I fancy one of those".

Other car makers, desperately seeking legitimate ways to meet carbon targets now that they've been caught fiddling the old tests, take note.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

A few years later and suddenly we're all going to be driving electric cars. Therefore, reason the world's investors, we'll need more batteries. That in turn means that we'll need more of the stuff that makes batteries.

(A brief pause while the world's analysts go away to read up on what goes into batteries.)

OMG we're going to run out of lithium!

Peak oil was one of the most seductive theories I've ever heard

The first time I heard the phrase "peak something" being applied to anything, it was in the context of "peak oil". Indeed, I believe that's what popularised the term (in finance at least) you can't escape from it now (though I'm always curious to know the origins of popular words and phrases, so if you can track it back further, let me know).

"Peak" oil as a theory had been around for ages. But it really took off during the first decade of the 2000s as oil prices rocketed.

At the time, it was very convincing. I was certainly persuaded. The experts who argued for it were sober and had plenty of statistics to back them up. There was a good case to be made that Saudi Arabia was fiddling its figures. The heart of the theory M King Hubbert's (correct at the time) prediction that US oil production would peak in 1970 had been proved right.

Anyone who disagreed sounded like a Pollyanna, particularly in the early days when absolutely no one but a select few believed in the theory.

And underlying it all, was a satisfying apocalyptic scenario that fitted well with storytelling structure. (That may sounds odd, but you have to remember at all times that we are storytelling animals any story that fits one of the big archetypes is always going to appeal to our brains. I'll talk more about that another day.)

Turned out it was wrong. Thank the Lord.

Oil prices rose so high that people were looking for it everywhere. Fracking in the US had already revolutionised the natural gas market, and explorers found ways to make it work for oil too. Now the US is Saudi Arabia unthinkable at the start of this millennium.

Today's "peak" argument is that we're going to run out of lithium. There's a good piece on Bloomberg by David Fickling just now, flagging up why you should be cautious of this thesis.

Fickling points out that estimates of lithium in the ground vary by a factor of ten. There may be as little as four million tonnes of the stuff, or as much as 40 million, depending on who you believe. That's enough for 100 million cars ("about 10% of the global auto fleet") to more than ten billion.

In other words, somewhere between "enough for now" and "way too much". Past experience would indicate that suggestions of "peak lithium" are hugely over-exaggerated.

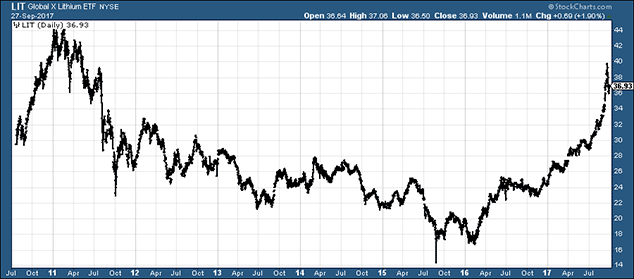

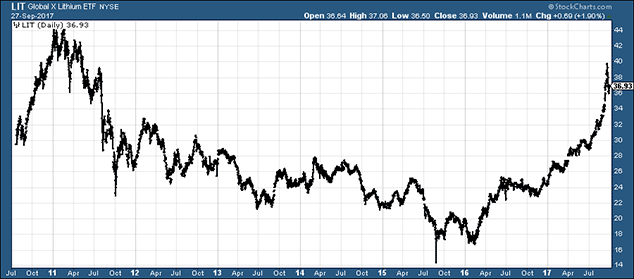

Nevertheless, here's the lithium ETF, LIT:

What "peak" really means

Playing with this stuff can be fun, but I want to make a point here "peak" arguments should never be believed. You can still make money from them in the short (and even medium) term, there's no doubt about that.

But LIT is most definitely an investment that you rent, rather than own. This is not a "buy and hold" by any stretch of the imagination. This is a trading sardine, not an eating sardine.

Because in the long run, peak arguments are always wrong, at least from an investment perspective.

I can hear the Malthusians sputtering into their coffee even as I type. I get that this sounds like an appalling, decadent, complacent way of looking at the world. And I'll never convince you that an apocalyptic shortage of something important isn't just around the corner.

But this isn't blind optimism. It's realism. Think about it. Even if we do run out of something that's vital to human life eg water then your portfolio becomes irrelevant. So even if you're right, it's a fundamentally unhelpful framework through which to view your investments.

And if there is a genuine shortage of a less important substance, then either the activity it underpins will be forced to come to a halt (so no electric cars, and therefore no profits to be had in that industry, and therefore no more use for that substance); or more likely a substitute that works almost as well will be found (so you end up getting batteries made from other types of exotic metals, and therefore demand for the "peak" substance falls).

The more likely solution is that a rising price will encourage explorers to look harder and use more technology in their hunt for the substance, and engineers to come up with new ways of using the substance more efficiently.

Before you know it wow, there's as much of this stuff as we need. In fact, we'd better stop making so much or we'll have a glut on our hands. Oops, too late. There goes the industry.

The point is that as long as you allow human ingenuity (incentivised by an opportunity to profit) to take its course, then "peak" arguments will never reach their logical (and potentially catastrophic) conclusions.

So when you hear "peak" arguments being made, all it means is that this is a cyclical business, and it's currently on the up. The louder the "peak" argument is being made, the closer to the top we are.

And once the anonymous fund managers on CNBC are lapping it up and churning it out, and the electric car ETFs are lining up to launch, you should be tightening up your stop losses and psyching yourself up to get kicked out of the trade and then turn your back on it until the next trough.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how