How to make big profits from the companies that spy on you

It’s not just governments that spy on you – companies do it too. Matthew Partridge explains how to get your hands on the profits they earn from your data.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

It's not just the US government that's spying on you private companies have been doing it for years. What can they do with what they learn? Make profits, says Matthew Partridge here's how to get your hands on them.

When Edward Snowden blew the whistle on the surveillance programmes of America's National Security Agency (NSA), the biggest surprise was not the extent to which the US government is spying on the world's personal data, phone calls and emails it was how cheap it is to do so. Storing and collecting that vast amount of information reportedly costs the NSA just $20m a year. Even then, it might be paying too much. According to consultancy McKinsey, you could now store all the music in the world on a disk drive costing less than $600.

Because it's so cheap and easy to collect and stockpile data, companies have gathered an awful lot of data on us too. Their aims may be a little less shady than those of the spy agencies most of them just want to sell us more stuff but as any good intelligence officer will tell you, gathering information is just one small step. You then have to analyse all this so-called big data', a much trickier problem.

Article continues belowTry 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In the early days of the information age, even those organisations that were forward-thinking enough to collate data on their customers didn't really know what to do with it. Senior managers were unwilling to trust the conclusions of data analysis, choosing instead to go with their own experience and insight opting for gut' feeling over hard evidence. In many cases this scepticism was warranted. Analysing data sets of this scale, and finding patterns that are actually meaningful and useful, is tricky.

But firms also missed huge opportunities to improve their businesses. For instance, in his award-winning book Moneyball, Michael Lewis tells the story of statistician Bill James. James's data-driven approach to baseball was widely mocked until one team, the Oakland Athletics (OAs), used his ideas consistently to beat teams that spent much more on players. The publicity around the book, however, resulted in other teams paying much more attention to statistics, which meant the OAs started to lose a lot more games.

Now a similar phenomenon is happening in both the public and private sectors around the world. Managers are waking up to the productivity benefits of analysing data effectively. McKinsey estimates that proper use of big data' could help to cut $300bn from the cost of US healthcare, and trim $200bn from the public sector in Europe (more than the GDP of Greece). With that sort of money at stake, it's little wonder that International Data Corporation, another consultancy, reckons that by 2016 nearly $24bn a year will be being spent worldwide on collecting and analysing data, and putting the insights gained to work. And that spells opportunity for investors.

How do you find big data'?

The initial challenge for any company or government that wants to take advantage of big data is collecting and storing the data in the first place. The complexity of big data means that the way this is done is undergoing its own revolution.

From the 1970s right up until today the computer industry has focused on creating structured databases. In the past this made perfect sense. Computers were primarily used to store information that was extremely simple, uniform and could easily be broken down into fields. A classic example is a payroll system: you have people's names, salaries, national insurance numbers and tax codes all data that is easy to categorise and applicable to each individual.

"By 2016, $24bn a year will be spent collecting big data'"

The trouble is, most data does not come in such an easily digestible format. Management theorists generally agree that just 10% of useful data is structured. The other 90% is incomplete, complex or poorly formatted. For example, let's say you have access to someone's Facebook posts, Twitter tweets and video files. Looking at all of those things could tell you a lot about a potential customer, but compiling it in such a way that a computer can analyse the data systematically is a huge challenge.

As a result, unstructured' databases (known as Not Only SQL' databases in tech jargon) are gaining increasing attention. These complement traditional structures, enabling users to keep track of data that is not uniform, or which constantly changes. This type of database is far more suited to storing large amounts of data and is less likely to be disrupted by small errors. It is also much easier to design.

What can you do with it? The next stage is to analyse the data, to spot patterns that can be used to improve productivity and performance. "With big-data analytics," says Mark P Mills of the Manhattan Institute, an American think-tank, "one can see beyond the apparently random motion of a few thousand molecules of air inside a balloon; one can see the balloon itself, and beyond that, that it is inflating, that it is yellow, and that it is part of a bunch of balloons en route to a birthday party." Examining such large data sets is a complicated and time-consuming business, requiring programming experience and statistical knowledge. However, these skills are not in ready supply. McKinsey estimates that by 2018 America alone will be short of nearly 200,000 people with the necessary skills. On top of that, an army of managers and analysts who can carry out more routine analysis will also be needed to work with the statisticians and programmers. Combining these two groups suggests that up to another 1.7 million people will be needed.

Faced with such a shortage, firms will need to consider alternatives. One option is to buy the expertise in by hiring consultants. Most of the big management consultancies are already eyeing this segment of the market, beefing up their technology units, or rebranding existing operations analysis services. However, they face competition from technology giants, such as Hewlett-Packard, which are also re-inventing themselves. Such companies are a natural fit, given that they are already largely staffed by people who are familiar with both statistical techniques and the software involved.

Another alternative is for companies to invest in software that makes large-scale data analysis easier, enabling those without a deep statistical background to look for relationships and patterns. Some of these programs are simply more user-friendly versions of existing statistical packages. However, other companies are trying to use the latest artificial intelligence software to scan through large amounts of data.

Two years ago IBM's Watson' artificial intelligence drummed up a lot of press interest when it repeatedly beat human champions at Jeopardy!, a popular American general knowledge quiz show. Watson is now being used to help doctors at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center to diagnose and treat patients more effectively. Watson, which can rapidly scan through millions of studies, is currently limited to lung cancer. But there are hopes it could quickly become a fixture in the doctor's office or even replace the doctor in some cases.

Who are the first-movers?

The final step in the process is applying the lessons learned from data analysis. The retail sector has always relied heavily on market research, so unsurprisingly it has been among the first sector to embrace big data. Supermarkets use data from loyalty cards to tailor their special offers to customers' shopping habits. And if you've ever bought anything through online retailer Amazon, you'll already have noticed that it recommends further purchases to you this is big data in action. Amazon has also been sharing data with Barnes & Noble about Kindle and Nook users. The aim is to help publishers produce better-selling books by giving them feedback on people's reading habits.

"Skills are not in ready supply. 1.7 million people will be needed"

But big data is spreading well beyond retail. The entertainment industry's creative remit is often seen as being at odds with sober analysis. But with production costs for film and television constantly rising, executives are keen to reduce the risk of flops, and so are starting to pay more attention to what the numbers are saying. For instance, before internet broadcaster Netflix invested in developing the mini-series House of Cards, it looked at its user database to see if there was an overlap between those who streamed the films of series star Kevin Spacey, director David Fincher, and political thrillers in general. In other words, they knew the size of a core audience who would almost certainly be interested in watching the series.

Drug and biotech companies have also enthusiastically adopted big data to improve the structure of clinical trials, find potential causes for diseases, and ultimately make it easier to come up with better drugs. The ability cheaply to sequence the human genome has also led to the rise of genomics', drugs that are tailored to individuals or small sub-groups. This is vital, as many types of drugs only work for a small fraction of the patients who receive them for instance, many cancer drugs only help 25% of patients.

Using big data to drive decision-making has also boosted productivity in public services. Starting in the 1990s, New York's transit police began to use crude statistical analysis to determine the allocation of officers. This was so successful in bringing down crime levels that the approach was extended to the whole of the NYPD, via the CompStat initiative. Although it met with some initial resistance from officers, the decision to use data, rather than instinct, to allocate resources, had a dramatic impact. The number of murders fell by 60% within a few years.

As collection and analysis has improved, the ability of police to fine-tune deployment has got even better. Santa Cruz Police Department has developed models that use past crime data to calculate the probability that a crime will take place within a specific 500 foot by 500 foot area, even if there have been no previous problems. This has enabled them pre-emptively to move police into certain streets before crimes were committed. In one example, almost immediately after the programme began, several people were arrested in the process of stealing cars. Overall, Santa Cruz's methods have enabled the state to keep the crime rate down, even in the face of budget cuts.

Financial institutions also sift huge volumes of data in the quest for an edge'. The US Federal Reserve, for example, looks at mortgage application search data on Google when considering monetary policy. Its studies have shown that this can help gauge the direction of the housing market. Of course, as the Fed shows, this approach doesn't necessarily lead to success: some problems are too complex even for big data to resolve. But plenty of money is being spent in the process of finding out where it can be put to good use. We look at the companies best placed to profit below.

The six stocks to buy now

Many of the best plays on big data are listed in America, which means you'll need a broker who can trade US stocks most of the major brokers should be able to do so. When it comes to storage and databases, the clear market leader is Oracle (Nasdaq: ORCL). The company also sells business intelligence software to help firms visualise and analyse the data collected. It is shortly due to release a new version of its main database management product, Oracle Database 12c, which is expected to boost sales of its database server, Exadata, substantially. Overall revenue from this segment could grow as high as $10bn a year, according to JP Morgan (currently, total revenues stand at around $37bn). Oracle has a solid balance sheet, with relatively low levels of debt, and trades at just under 11 times 2014 earnings.

Another play on data storage is EMC Corporation (NYSE: EMC), which controls nearly a third of the market for data warehousing. As well as looking to grow its market share, the company also wants to broaden its focus into analysis. Three years ago it bought a business intelligence unit, Greenplum. EMC has a healthy balance sheet, which will enable it to expand and invest in new technology. It has also started paying a dividend. EMC trades at 13 times 2013 earnings.

Although it used to be best-known as a computer hardware company, IBM (NYSE: IBM) now focuses far more on data consulting. It now gets well over half its revenue from providing software and business support services to firms around the globe. It is one of the market leaders in database and data analysis, with a broad portfolio of big data products. Despite a downturn in Chinese business, global sales are still growing strongly. On 12.6 times current earnings, below the average for the wider US market, it's a great all-round play on big data.

London-listed software group WANdisco (Aim: WAND) helps firms manage data in real time (ie, as it's being created). It recently closed a major deal with mobile telecoms group Nokia. It is due to launch several new products, and recently bought a website popular with web developers, which will help boost its profile among potential customers. This should help WANdisco continue its explosive growth, with turnover set to triple in the next three years. While it's currently loss-making, its long-term prospects mean it looks worth buying for those with an appetite for risk.

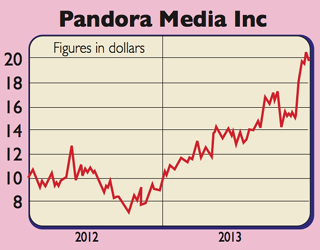

One company benefiting from using big data is internet radio station Pandora Media (NYSE: P), which uses maths to automate the role of music DJ. Pandora takes its library of nearly a million tracks and breaks them down into their constituent parts, based on tone, pitch and other variables. It uses this database to produce a personalised playlist for each user, based on songs musically similar to their existing favourites. Currently loss-making, JP Morgan expects it to return to profitability by next year and for revenues to grow by around 30% a year for the next five years.

1Spatial (Aim: SPA) is a consultancy and software company that focuses on location-related data: essentially big data that can be visualised. The decision to specialise in this niche market means it has won contracts with Ordnance Survey and other mapping and maritime agencies, including those in Germany, New Zealand, Sweden and Ireland. It is also developing links with defence firms, property companies, utilities and the mining industry. Although it is still in the growth stage, it has more than enough cash to tide it over until it becomes consistently profitable.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.