The very ugly truth about RBS

It's no secret Britain's banks are still in a mess. What isn't so clear is just how much of a mess, says James Ferguson.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

I wanted to talk to you today about a topic that is on everyone's lips at the moment: the re-privatisation of RBS. Because I think there is a disturbing story here that is not being widely reported in the mainstream press. And it goes right to the heart of the economic problems that Britain will face over the next few years. It certainly affects your investments.

When Stephen Hester took the head job at RBS, he was given the task of shrinking and de-risking the bank. The ultimate goal was to bring about a sufficient recovery so that the government could reprivatise at a higher share price, and make back the €45bn they had invested in 2008-9.

Now that Stephen Hester is being pushed out to make way for a new head of RBS who will take the bank private again before the end of 2014 the market is speculating about just how fixed the UK banks now are.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Stock prices have rallied strongly from the lows, though they are still well below where the government bought shares in Lloyds and RBS on our behalf. However, with the political timeline fixed for a sale ahead of the next election in 2015, the story about the banks' solvency has become political. And that is where this story gets a little dirty

Why these banks can't lend

The trouble with banks is that the public rarely knows the true health of their balance sheets. The big four British banks Barclays, Lloyds, RBS and HSBC all had strong balance sheets (by which I mean they reported strong capital ratios) ahead of the crisis. But it turned out all was not as it seemed when disaster struck. And since then investors have largely been operating in the dark.

Still there's nothing like a share price rally to make your average broker believe that the banks' balance sheets are fixed. The problem is that every historical precedent has shown the banks to be hiding bad debts on their balance sheets for several years before they finally get fixed. In the wake of a serious banking crisis, banks can't show the full extent of losses because these would wipe out too much of their capital, so they parcel out losses against earnings over time.

The way we, the public can see that the banks are hiding losses (though we can only ever guess how large these may be) is by watching their behaviour. No matter how fixed a bank claims it is, no bank has ever been shown to shrink loans when policy was easy unless it was subsequently shown that the bank in question was suffering solvency issues. Therefore if the banks really are fixed, we will see it in the form of rising bank lending. After all, the banks are sitting on record amounts of unused liquidity in the form of excess bank reserves, so there's absolutely no liquidity constraint.

Well, up until the start of 2012, record liquidity and the lowest base rates for over 300 years had done nothing to encourage the banks to lend. How could they? As we know, they were sitting on further as yet undeclared and capital eroding losses. How big are those losses?

Well, we don't know exactly. Investor consultancy PIRC reckons that hidden losses at British banks come to a total of £40bn. I wouldn't be surprised if losses were five times that size. Here's the rub. The big four British banks sport some £255bn in core tier 1 capital, so if hidden losses of £200bn were to be revealed, so would the fact that the sector is still practically insolvent. Banks have already realised £230bn of losses, but that has taken almost five years of earnings.

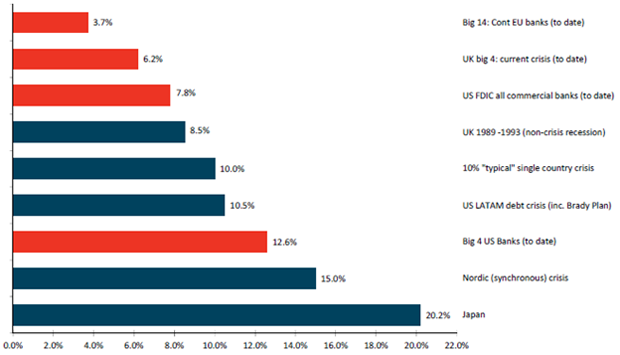

The figure below shows how much progress banks have made towards repairing their balance sheets.

Bank Cumulative Loan Write-Offs as a Percentage of Peak Assets

Source: Companies data, Westhouse Securities

As you see, in a typical banking crisis, banks end up having to write off about 10% of their loans. In a bad crisis, they write off 15%. If it's a Japanese scale crisis, they write off 20%. That can take anything between five and 15 years to play out. And the big four have made very little progress so far compared to their US counterparts.

Since 2008, US banks have written-off 12.6% of their loans. And so they may soon be strong enough to start lending again. But the big four UK banks have only written down 6.2%.

Another big problem is that half the sector's capital resides at just one bank: HSBC. But because HSBC has also done more loan-loss realisation than any other bank, it's a really good bet that far less than half of the remaining losses will come from HSBC.

That leaves the other three banks, RBS, Barclays and Lloyds, in a tricky position. As hedge fund manager Chris Hohn pointed out in a letter to the Financial Services Authority earlier this year, a £20bn post-tax loss would send Lloyds' capital ratio below 5%. The same would also be true for the other two banks.

That's because liquidity is not the real underlying problem here.

Even the government has fallen for this ruse

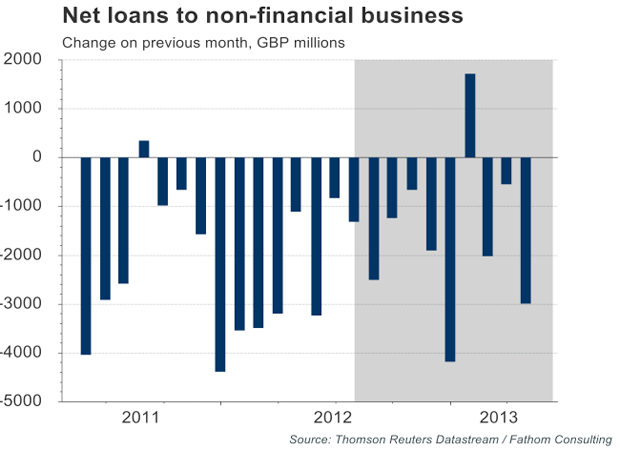

Still the government, believing what the banks say about a lack of demand and other guff, bring in the Funding for Lending Scheme (FLS), since when, as the chart below illustrates, bank lending to businesses has with the exception of one month, continued to contract.

What does this tell us about the likely success of the newer, brighter, FLS Max? Exactly what we already knew and have known since the banks' commitment to increase lending to businesses by £190bn in a year (an increase of £76bn to SMEs) under the terms of February 2011's Project Merlin deal with the government.

Year in, year out, the banks promise to lend, the government does a deal to ensure it will happen and the banks then renege. They have to renege because their problems are not liquidity or cost of funding or lack of demand.

The banks face the same problem all banks face during a post-crisis resolution: hidden losses on legacy loans that if accounted for today at market prices would wipe out most or all of their capital.

What this means for your investments

Bank of England governor Mervyn King knows all this. As will Mark Carney when he takes up the job in a few week's time. King had already advised the Bank for International Settlements (the central bank for central banks) to relax the liquidity requirements on British banks. At a time when central banks are offering plenty of cheap emergency funding, it seems pointless to make banks hold extra liquidity.

For one thing, if you do, they might use it as an excuse to avoid any type of risky' lending. This hinders any economic recovery. Another worry is that you could inadvertently trigger another type of liquidity crisis by forcing banks to scrabble for risk-free' collateral to hold.

But the governor's main point is that liquidity is just a recurring symptom. The real problem is that banks are concealing massive private debts large enough to wipe out their entire capital.

So why have bank shares bounced? Markets understandably find it hard to quantify risks that banks don't bother to include in their accounts. So they love the news that share prices are rising and regulations are being eased.

Most analysts focus on the profit and loss account, rather than on the balance sheet. So as far as they can see, the only problems now facing banks are regulatory and funding constraints. The recent Basel regulations relax both, which seems like great news.

However, the real threat lies on the banks' balance sheets, in the form of these hidden losses. These banks won't turn their reserves back into loans until their balance sheets are fixed and no hidden losses remain. One thing is for sure, we're a long way away from that day. And that could have a serious knock on effect for almost all assets from stocks to property.

James Ferguson recently launched The MacroStrategy Partnership LLP with ex-UBS veteran Andy Lees, and has over 25 years' experience as a stockbroker and market strategist. He is a regular contributor to MoneyWeek. And has just joined The Fleet Street Letter where he'll be writing about everything from UK property to the state of British banks.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

James Ferguson qualified with an MA (Hons) in economics from Edinburgh University in 1985. For the last 21 years he has had a high-powered career in institutional stock broking, specialising in equities, working for Nomura, Robert Fleming, SBC Warburg, Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein and Mitsubishi Securities.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.