Why Asia doesn't need exports to grow

With Asia's growth traditionally powered by exports, the global slow-down meant less demand for the continent's goods. But as Asia's domestic economies stage their own recovery, they will no longer be as dependent on exports to the West. Cris Sholto Heaton explains why.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Decoupling has undergone a swift fall from grace. All the rage last summer, when markets hoped that Asia could sail on as the US faltered, the idea today is about as credible as Flat Earth Theory.

So I'm reluctant to say that the phrase could make a comeback in the next couple of years. But I wouldn't bet against it. Because decoupling may not have been totally wrong just the wrong way round.

The idea that Asia could shrug off the loss of its major customer was clearly misguided. A US slump was always going to mean a global slump. The more interesting question is whether Asia can pick up speed again, even as the rest of the world remains sluggish.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Trade is reaching a bottom

Since most Asian economies are major exporters, the first thing we need to see before a recovery is a stabilisation in world trade. It's impossible for a country such as Taiwan to grow while its exports are in freefall; as you can see in the chart below, the collapse late last year saw its economy shrink at the fastest rate since this series began.

So the good news is that this stabilisation seems to be underway. I pointed to the first hints of this in Korean and Taiwanese exportsback at the end of March (Why Asian investors are more upbeat than Europeans).

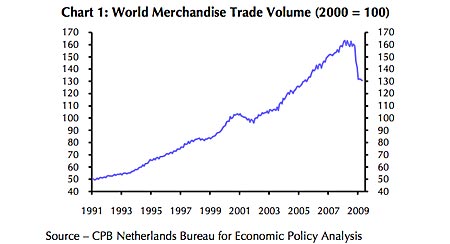

The chart below shows that things are now settling down for most countries, with world trade volumes flattening out after that shattering plunge.

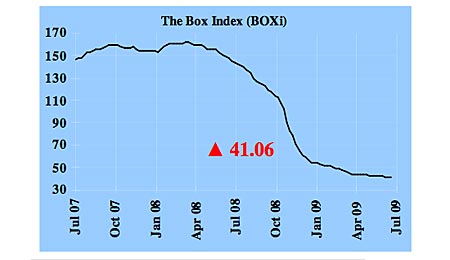

The data above only goes up to the end of April, but container-shipping rates suggest the process is continuing. Shipbroker Braemar Seascope's BOXi container freight rate index seems to be bottoming, despite the amount of oversupply in the industry. Indeed, shipping lines now seem to be bringing a bit more capacity back into service in response to improving conditions; the percentage of the fleet that's been laid-up is down to 9.70% from a high of 11.3% in March, according to shipping research firm AXS-Alphaliner.

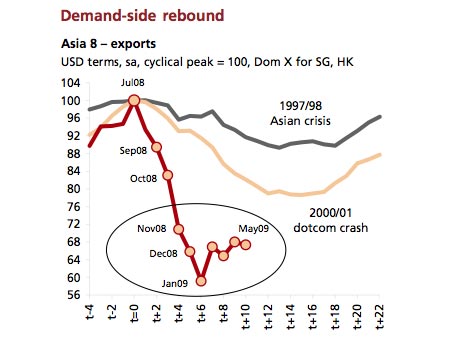

Data from the Asian countries who have reported May exports so far tell the same story. Shipments have rebounded from their January lows and have been flat to slightly rising for the last four months.

Western growth will be slow

So far, so good. But stabilisation is not growth. While we can expect volumes to pick up a little more from here, we're certainly not getting back to that 2007 level this year or next, or even in 2011.

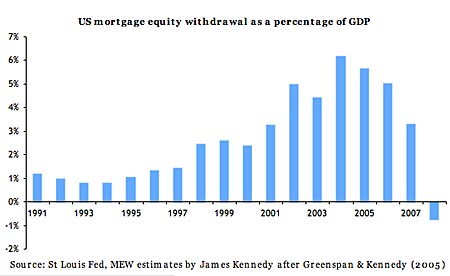

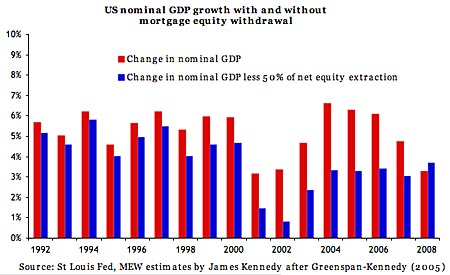

As you know, the West has been living beyond its means for many years, thanks to excessive borrowing. The chart below shows mortgage equity withdrawal (MEW) in the US loans taken out against the rising value of people's property.

This MEW boosted imports for consumption, bid up asset prices and helped the economy grow faster than it would otherwise have done. In the chart below, I've compared the nominal (non-inflation-adjusted) change in US GDP with the change minus 50% of MEW (50% being a common estimate of how much of MEW went directly into the domestic economy).

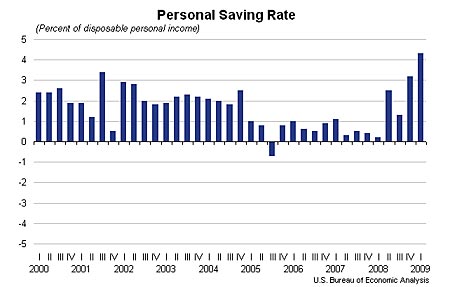

This is a very, very crude way of looking at the problem but it gives a feel for how important MEW was for growth. Now, without this extra consumption boost from borrowing against rising property values, Western economies are going to be growing much more slowly, especially since consumers will trying to pay off this debt burden. The US personal savings rate is now up to 6.9% of disposable personal income, as you can see below.

Asia has little debt

That sounds like it should be a huge problem for many Asian economies. If their growth has been powered by exports, then slower-growing Western economies and more frugal consumers will mean less demand for imports from Asia.

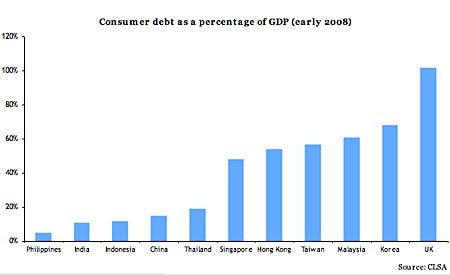

But Asia has one thing in its favour: low debt. As you can see below, debt levels in most regional economies are way below the levels we see in America and Britain. That means the Asian consumer is not burdened with the problem of paying down their outsized mortgages and credit cards.

However, as long as plunging exports are subtracting from growth as they did over the last couple of quarters, there's no way that domestic consumption and investment can compensate especially when you take into account the effects of the export plunge on business plans, unemployment and consumer sentiment. This was the fatal flaw in the decoupling theory.

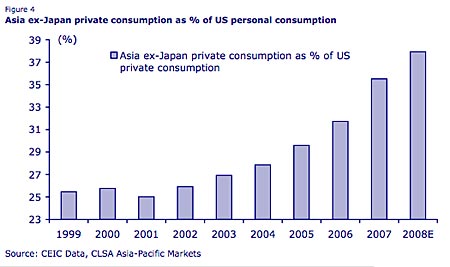

But a different type of decoupling is certainly possible for Asia: gradual decoupling on the way back out of the recession. Asian consumption has grown at a healthy pace over the last eight years, as the chart below shows it's just that exports have grown even faster (and hence consumption has fallen as percentage of GDP).

Once exports stabilise, Asian economies can begin to grow again - but this time it will be their low-debt domestic economies that are growing, not the sluggish export sector. They'll be growing from a lower base the size of the export sector will have been reset to 2005-2006 levels and it won't be rebounding any time soon. And because of this it could easily be three or four years before some economies are as large again as they were at the peak. But they will be growing and growing faster than deleveraging Western economies can manage.

The adjustment has already begun

Obviously, adjusting to this new world without the export engine will take time. Some economies will do it faster than others. As I discussed here: China will be fine - but don't expect it to save the world, exports seem to have been more of a turbocharger to Chinese growth than a key component; so it should be able to accelerate to 8-10% again reasonably quickly.

The biggest concern in China is the possibility of excessive lending, unproductive investment and bad loans in the banking system. This is a risk if the current lending boom goes on too long, but right now I still think it's too early to worry about this.

For emerging Asia's other two big domestic-demand economies, access to credit is more important. India and to a lesser extent Indonesia benefited from a world awash in easy money and both saw a nasty credit crunch as this dried up. But conditions are improving: markets re-opened just in time to allow a number of stressed Indian companies such as the major house builders and Tata Motors to raise equity or refinance (a little later and we could have seen some high-profile failures).

This has happened more quickly than I expected and recent data out of both has been encouraging. I still have some reservations especially India's enormous budget deficit but as long as we don't get a prolonged new freeze as markets realise that the US recovery is going to disappoint, both look like they're back on track for 5%-7% growth next year.

Recovery for the most export-dependent economies such as Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore and Taiwan will probably take longer. Unlike 2001-2002 or the aftermath of the Asian crisis, there isn't the strong global demand to propel them into a V-shaped recovery through their export sectors.

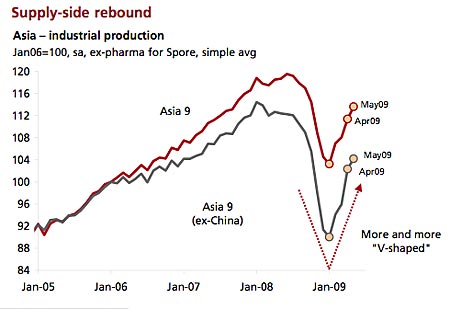

They can certainly be growing again by the end of this year: we're already seeing some tentative signs of improvement, such as three months of rising retail sales in Taiwan. Industrial production has also rebounded more than exports, which could point to improving domestic demand (although it could also mean that manufacturers are getting ahead of themselves).

It's likely that next year will be weak by Asia's standards especially in these smaller economies. But it should be healthier, more balanced growth. The inevitable end of the export boom exposed the flaws in the Asian model, but they are not fatal flaws. The foundations for the next stage are coming into place. Over the next few months, Asia should begin to outperform the rest of the world and the Asian growth story will be underway once more.

In other news

table.ben-table table { border: 3px solid #2b1083;font: 0.928em/1.23em verdana, arial, sans-serif;}

th { background: #2b1083; padding: 10px 5px;color: white;font-weight: bold;text-align: center;border-left: 1px solid #a6a6c9;}th.first { border-left: 0; padding: 5px 2px;text-align: left;}

tr {background: #fff;}

tr.alt {background: #f6f5f9; }

td { padding: 5px 2px;text-align: center;border-left: 1px solid #a6a6c9;color: #000;vertical-align: center;}td.alt { background-color: #f6f5f9; }td.bold { font-weight: bold; }td.first { border-left: 0; text-align: left;}

| China (CSI 300) | 3,128 | +1.6% |

| Hong Kong (Hang Seng) | 18,600 | +3.8% |

| India (Sensex) | 14,765 | +1.7% |

| Indonesia (JCI) | 2,040 | +2.5% |

| Japan (Topix) | 927 | +0.9% |

| Malaysia (KLCI) | 1,076 | +1.5% |

| Philippines (PSEi) | 2,477 | +3.3% |

| Singapore (Straits Times) | 2,318 | +2.0% |

| South Korea (KOSPI) | 1,395 | +0.8% |

| Taiwan (Taiex) | 6,464 | +3.7% |

| Thailand (SET) | 596 | +1.2% |

| Vietnam (VN Index) | 461 | -2.9% |

| MSCI Asia | 94 | +2.5% |

| MSCI Asia ex-Japan | 389 | +3.0% |

Last week was dominated by banking news. Spain's Banco Santander is reported to be in talks with China Construction Bank, the country's second-largest bank by assets, to set up a rural banking joint venture in China. Santander has been one of the few winners from the global banking crisis, snatching up several assets on the cheap; several other firms such as Bank of America and RBS have been obliged to sell off their investments in China's top banks to raise capital.

China Minsheng Banking Corporation, the nation's first privately owned lender, won approval to list on the Hong Kong stock exchange. The group, which is already listed in Shanghai, needs to raise RMB20bn (US$2.9bn) in new capital to bring its capital adequacy ratio up to the minimum 10% demanded by Chinese regulators.

Banking enthusiasm for Cambodia seen as the next frontier market in Asia is growing. Sacombank, Vietnam's sixth-largest lender by assets, is opening its first branch in Phnom Penh, targeting cross-border business between Cambodia, Vietnam and neighbouring Laos. It's the third Asian bank to open a Cambodian division since May, following South Korea's Kookmin Bank and State Bank of India.

And Standard Chartered, the emerging markets-focused bank with two-thirds of its business in Asia, said that it had earned record profits in the first five months of the year. The firm said it remains "cautious on the outlook", but the overall tone was more upbeat than in its last results announcement in March.

Finally, in one piece of non-banking news, private equity group Bain won the race to take a stake in Gome, China's second-largest electronics chain. The retailer has been under pressure for several months after its founder was arrested, reputedly for stock manipulation, and was said to be struggling to get financing from suppliers and banks. Gome's shares leaped almost 70% in Hong Kong after its shares were readmitted to trading for the first time since November.

This article is from MoneyWeek Asia, a FREE weekly email of investment ideas and news every Monday from MoneyWeek magazine, covering the world's fastest-developing and most exciting region. Sign up to MoneyWeek Asia here

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek Talks

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek TalksPodcast Clare Francis, savings and investments director at Barclays, speaks about money and mental health, why you should start investing, and how to build long-term financial resilience.

-

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change looms

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change loomsChanges to inheritance tax (IHT) rules for unused pension pots from April 2027 could trigger an ‘exodus of large defined contribution pension pots’, as retirees spend their savings rather than leave their loved ones with an IHT bill.