Profit from the tech spending slump

Those technology firms that survived the dotcom bust of the late 1990s have spent much of the time since hoarding money. Now they are one of the few industries with spare cash, and there is talk of a tech-led recovery. Eoin Gleeson investigates, and picks the best bet in the sector.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Shuttered shop windows and long queues at discount stores are the obvious signs of recession. Others are much less visible. Take IT companies have been scaling down the computer hardware they use to support their operations for months. And in the their storerooms, unused PCs are piled high and gathering dust. Indeed, according to a report just released by research group Gartner, this year has seen the worst-ever slump in spending on global IT. Worldwide, hardware spending from printers to PCs and servers is forecast to total $317bn, a 16.5% drop on 2008.

And this is the second severe meltdown for IT in a decade. So the IT firms that survived the late 1990s spent much of the cheap debt-fuelled rebound hoarding cash and generally running their business as if they were operating out of a bunker. Now they are in one of the few industries to boast spare cash. So suddenly there is fresh talk of a technology-led recovery. Last week saw a clutch of robust earnings from IBM, Intel and Google. Meanwhile, the tech-heavy Nasdaq has surged 70% since March.

Supporting this rally is the belief that the interruption in corporate spending "the lion's share of tech demand" will end as the financial crisis passes, says Richard Waters in the FT. Having foregone spending on computer hardware during the recession, companies will need to move fast to replace out-of-date machines.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Approximately one million servers have had their replacement date delayed by a year that's 3% of the global installed base, according to Gartner. The trouble is that the managers who make the technology purchasing decisions haven't opened their wallets yet. And while they are always worried about the financial impact of old equipment failing, they know that there are cheaper ways to improve their IT operations than replacing old with new.

Consumer-products giant Unilever is a good example. It has an annual storage requirement growth rate approaching 50%, according to Computing magazine. So it can't keep building huge server farms to back up operations. Instead, the firm has to try to use what it has more efficiently. Windows, for example, has typically only allowed one application to run on a server at one time before it crashed. But this can be solved using a program called a hypervisor a sort of electronic traffic cop that controls access to a computer's memory.

Now Unilever's servers can run several applications at the same time by splitting the machine into multiple 'personalities' (in effect, computer programs then operate as if they were machines). This is called virtualisation and it radically improves the capacity of a data centre. You need less floor space and you save a fortune on air conditioning. Some of Unilever's networks approach a virtualisation level of 95%, according to Computing's Dave Bailey.

Another way firms are cutting IT costs is by outsourcing data centres altogether. This drive towards utility (or cloud) computing is no longer new, but now Wall Street is getting in on the game. Banks search out buildings close to stock exchanges to house data centres in a bid to shave milliseconds off the execution times for trades a space of 100 miles equates to a full second. That's why NYSE Euronext has secured a space the size of three football pitches in an industrial park 30 miles outside London, according to Jeremy Grant in the FT. The racks of comacputers will sit in vast, bomb-proof halls. We have a look at one stalwart leading the virtualisation and utility computing drive below.

The best bet in the sector

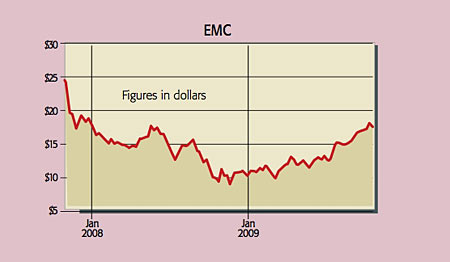

EMC (US: EMC) has the makings of a major data utility, according to Nicholas Carr in his book The Big Switch. There are two sides to its business. First, it is the leading group in data storage equipment providing the equipment and software that helps companies store, manage and retrieve all their data. Demand for data storage is expected to grow 60% annually, according to NewYork-based Pershing Square Capital. The group will see strong demand in particular from the financial services, according to Barclays Capital analyst Ben Reitzes.

Second is virtualisation. EMC's 82%-owned subsidiary VMware is the dominant force, owning 80% of the market and virtualising everything from desktops to data centres. Over the last five years EMC's revenue has grown at a compound annual rate of 19%. It has $6bn of cash on hand, with $3.24bn in long-term debt, and generated free cash flow of $1.1bn during the year to date. Its shares have surged 42% since we tipped them in April. But with such a dominant position in virtualisation and data storage, the shares are still attractive. EMC trades at a significant discount to its peer Netapp, valued on a forward p/e of 15.2.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Eoin came to MoneyWeek in 2006 having graduated with a MLitt in economics from Trinity College, Dublin. He taught economic history for two years at Trinity, while researching a thesis on how herd behaviour destroys financial markets.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement today (3 March). What can we expect in the speech?