What's so alarmed the chartists?

Richard Russell, one of the best-known investment chartists, is worried. Why? It's all in the indices, as Tim Bennett explains.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

"The curse, it is cast the monster is creeping towards Bethlehem." No, it's not the opening line of the latest horror blockbuster. It's just one of a string of recent warnings from Richard Russell, one of the investing world's best-known chartists. The editor of the Dow Theory Letters newsletter has been telling his readers to bail out of US stocks since 20 May. So who is he, and what's so alarmed him?

Who is Richard Russell?

Russell has been watching the Dow Jones closely and investing accordingly since 1958. Over a long career he has successfully called bull-market tops (between 1949 and 1966) and bottoms (such as 1972-74). And right now he thinks stocks are in big trouble. It's all down to 'Dow Theory'. This was born out of Wall Street Journal editor Charles Dow's analysis of market price action for shares in the late 19th century. But because Dow himself never formalised his ideas, later writers such as William Hamilton (1902 to 1929), Robert Rhea (who wrote 'the Dow Theory' in 1932) and Richard Russell were responsible for developing it. And all four share some core beliefs key to grasping the theory.

How to think like Dow

Like most chartists, Dow Theorists believe that stock prices reflect absolutely everything that is known or can be known about a share. Every investors' hopes, fears and expectations are 'in the price'. That matters, because Dow Theorists believe that what they call key 'primary trends' cannot be manipulated when the theory says 'sell', woe betide the investor who ignores the signal. According to Jack Schannep, author of Dow Theory for the 21st Century, this is borne out by the statistics. An investor who had followed all the Dow Theory buy and sell signals since 1960 would have made double the returns of a buy-and-hold approach over the same period. So how does it work?

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Dow Theory in practice

The two oldest surviving US stock indices are key. The first is the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA). This is an index of the leading 30 US stocks (including Coca-Cola, Walt Disney and General Electric). The second is the Dow Jones Transportation Average (DJTA), which includes 20 transport firms such as logistics group Fedex and Delta Airlines. The DJIA has been a barometer of the US economy's health for decades. The DJTA shows how confident US firms are about future demand higher confidence levels translate into higher levels of expected orders, which in turn requires stock to be moved by road, rail or air.

Dow theorists divide stockmarket moves into three types. There's the 'primary trend'. These last for anything from a few months to years and signal whether you are in a bull or bear market. Once a primary trend is established, Dow Theory does not try to predict how long it will last. The primary trend simply continues until there is a clear signal that it is over. Then there are 'secondary trends'. These usually run counter to the primary trend, but do not dislodge it. In a bear market, some analysts call these 'reaction rallies' (a short uptick lasting maybe a few days). In a bull market, they are short-term 'corrections'. Lastly there is 'noise' daily fluctuations based on market sentiment. These are largely irrelevant for anyone other than a day trader.

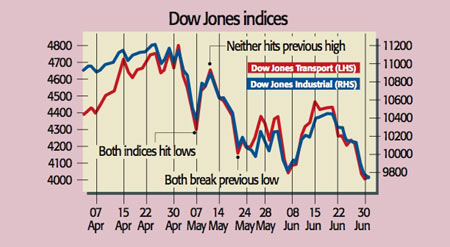

The exact mix of primary and secondary trend moves needed from the two indices to give a clear 'buy' or 'sell' signal is complex, and subject to debate. But it can be summed up as follows. First, a bear market, or 'primary down trend', is revealed by a correction in both indices from a previous joint high. Next, in the secondary upward move (the 'bear market rally', if you like) that follows, one or both indices must fail to rise above their pre-correction highs. Both indices must then drop below their correction lows. In a nutshell, you look for a joint peak, then a 'lower high' and a 'lower low'.

Enter Russell. After the May 'flash crash', both indices hit lows on 7 May then rallied 5% (DJIA) and 8.4% (DJTA) respectively. But neither beat its earlier 'pre-crash' high. Then on 20 May, both broke below their 7 May lows. Not all Dow watchers think Russell is right about timing (Schannep doesn't believe the rally after 7 May was significant). But no Dow Theorist could be described as bullish right now, and Russell has the most form. As far as he is concerned, the US is now in a bear market and any brief rallies are "meaningless".

The best ways to short the market

We wouldn't base investment decisions solely on Dow Theory or any other charting. But the fundamentals also look gloomy. If you have the stomach for shorting, you could try spread betting (see www.moneyweek.com/SB.aspx for more). But as the 'primary bear trend' could last some time, an alternative (that saves you having to constantly roll over bets) is an inverse exchange-traded fund (ETF) such as the Proshares ShortDow30 (NYSE: DOG). It rises as the Dow Jones falls and vice versa.

Be aware that this is not a 'buy-and-hold' investment. Thanks to a pricing quirk (ETFs are repriced daily), the performance will not always be the exact inverse of the index, and the more volatile markets are, the worse it becomes. If you do have a punt, check your position regularly and don't risk money you can't afford to lose.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Tim graduated with a history degree from Cambridge University in 1989 and, after a year of travelling, joined the financial services firm Ernst and Young in 1990, qualifying as a chartered accountant in 1994.

He then moved into financial markets training, designing and running a variety of courses at graduate level and beyond for a range of organisations including the Securities and Investment Institute and UBS. He joined MoneyWeek in 2007.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge