What is a profit warning?

Ed Bowsher explains what a 'profit warning' is, and how you should react if a company you own warns that profits will disappoint investors.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

There's lots of confusion out there about what a profit warning is. Even Wikipedia has its wrong.So in this video, I explain what a profit warning is, and how you should react if a company you own warns that profits will disappoint investors.

Video transcript

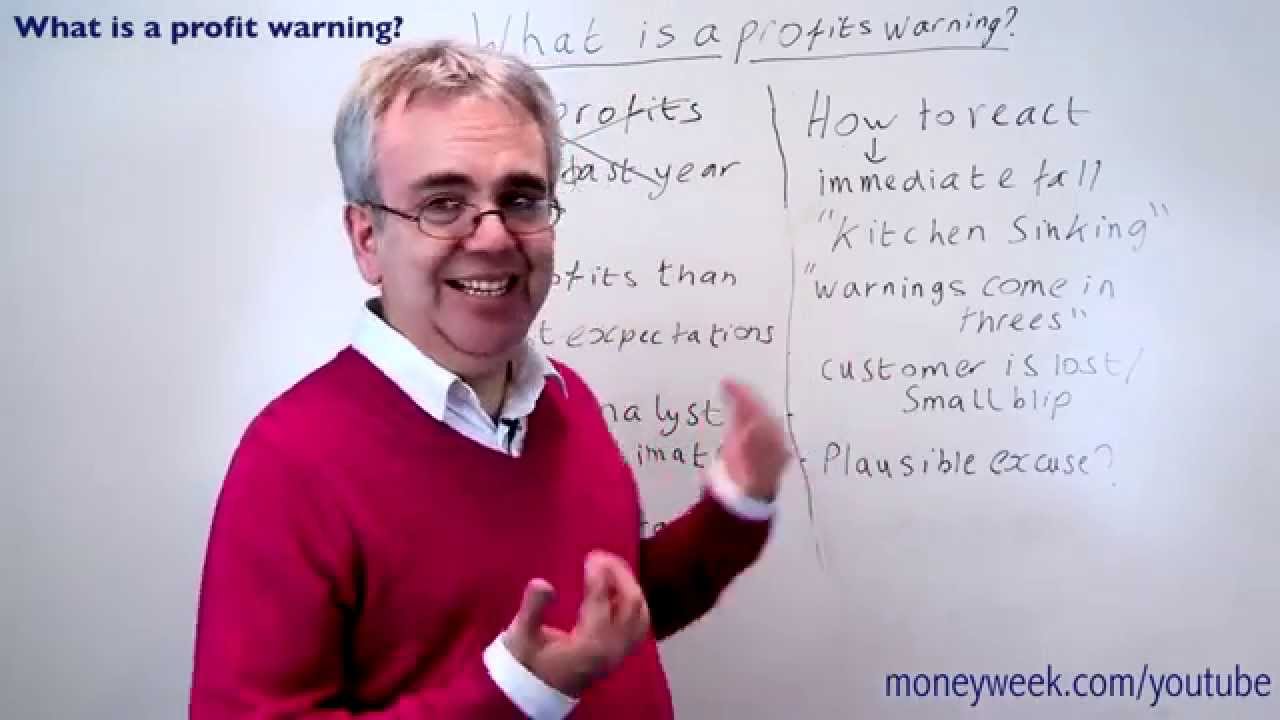

So what exactly is a profit warning? Well, I looked at Wikipedia just quickly before I starting shooting this video. They said a profit warning is when a company will make lower profits this year than it made last year. Actually, though, sorry Wikipedia - that's wrong.

What a profits warning actually is, is when a company knows that this year it's going to make profits that are lower than the current market expectations, the current analysts' expectations if you like.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

We've already looked at analysts, but what are City analysts? Basically these guys - and they're mostly guys - are highly-paid number crunchers who issue buy', sell', and hold' ratings on companies. They also give forecasts on what profits are expected to be this year, next year, and the year after. Normally, these analysts chat with the company involved and get some guidance from the finance directors. The finance director would never give them a precise figure of what the profits are going to be; they guide analysts toward the right ballpark.

When you've got a big company - someone like Tesco - you'll have 20 or 30 analysts following the company, so you'll get lots of different forecasts. You average out those forecasts and you get the consensus expectation for that company's profits for this year and for next year. If the company concerned knows that the forecast is wrong, they've got to tell the market immediately. The expectations need to be changed. So the company issues a profit warning.

Now, if you want to find out what the analysts' expectations are, even in the City, they will just be able to quickly find the figure on their Bloomberg or Reuters screens. But private investors can also find these numbers. Go to the Yahoo Finance website. If you're interested in Tesco, go to the Tesco page on Yahoo Finance. There you'll see links on the left-hand side, including one saying "analysts' estimates". Look at that link, and you'll see the market estimate for what Tesco is going to do this year.

You own a company where there has been a profit warning. How do you react?

So, fine; you own a company where there has been a profit warning. How do you react? Do you immediately sell your shares, do you wait a little while, or do you just carry on holding it for the long term?

Well, the first point to make that's really important here is that no matter how quickly you react to the profit warning, you're going to be too late in terms of beating that immediate fall in the share price.

As soon as the profit warning comes out, as soon as trading begins after the profit warning, you'll see an immediate fall in the share price; just like that. You can't beat it, and you won't be able to sell your shares at the pre-warning price. Or it's highly unlikely, anyway. So don't try to do that; you won't be able to.

So what do you have to do if the profits warnings come out, and you've seen the share price has fallen? Do you just panic and bail out, or do you decide to hold on?

The crucial point is don't panic. Stay calm, then decide what you're going to do. Analyse it bit deeper. Now, it may be the case that the profit warning is actually an example of what's known as kitchen sinking'. We saw an example of that last week when Shell put out a profit warning.

Now, until last week, Shell hadn't issued a profit warning since 1998. But the company just hired a new chief executive - Ben van Beurden. He's only been doing the job for three weeks, and he's decided to put out a profit warning really quickly. That often happens with new bosses because they want to start from a low base. They want things to look really bad when they start and then when things improve they'll look better - they'll get all the glory for doing a fantastic job. So he'll look for all the problems, he'll write down the value of the assets on the company's balance sheet. He'll throw everything out, including the kitchen sink, to make things look really, really bad. So if you see a profit warning from a company where a new boss has just come in, you should probably stay invested. The new CEO is just playing a game; he's kitchen sinking.

There's another good stock market saying you'll often hear: "profit warnings come in threes". Often, if you see a company that is having real problems, it'll release its first profit warning. Then things get worse, and you'll get another one, say three months later. And maybe another one a year down the line. This is where a company has a more deep-seated malaise and structural problems that it's struggling to deal with.

Think about the excuse for a profit warning and ask: is that excuse really plausible, are they really telling me the truth?

Retailers are a good example. You'll often see profit warnings coming out where it's just a relatively small blip. A retailer might say that sales over the last three months have been disappointing, lower than expectations, because we bought the wrong kind of skirts and we didn't get the right judgment on fashion this quarter.

If you are supplying parts to Apple for the iPhone, and if Apple delayed the launch by three months, then fine. It's just going to be a temporary blip in your chip sales. Three months later the new iPhone will be launched, and sales will go back up as expected. The problem was only short term.

Another thing I like to do is to think about the excuse a company gives and ask: is that excuse really plausible, are they really telling me the truth?

With retailers again, I've often seen a retailer blame a poor quarter on bad weather. There was lots of snow before Christmas, and sales were lower than expected. Well, that sounds good, but if company A uses this weather excuse and then two weeks later company B says, hey, guys, we had a great Christmas regardless of the weather. Suddenly you're thinking company A didn't tell me the truth there. Company A has more serious problems than just the weather, and I know they're not telling me the truth because they're a bunch of liars, or they're not telling me the truth because they're lying to themselves and not dealing with the more serious problems that the company has. That would make me very nervous and I'd very seriously consider selling.

But it's never easy when you get a profit warning to know what to do; there's no simple answer. If there was a simple answer we'd all be millionaires. But hopefully I've given you a few ideas on how to approach it.

So that's it for this video; I'll be back in a couple of days with another one. So until then, good luck with your investing.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Ed has been a private investor since the mid-90s and has worked as a financial journalist since 2000. He's been employed by several investment websites including Citywire, breakingviews and The Motley Fool, where he was UK editor.

Ed mainly invests in technology shares, pharmaceuticals and smaller companies. He's also a big fan of investment trusts.

Away from work, Ed is a keen theatre goer and loves all things Canadian.

Follow Ed on Twitter

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

By Laura Miller Published

-

How to navigate the inheritance tax paperwork maze in nine clear steps

How to navigate the inheritance tax paperwork maze in nine clear stepsFamilies who cope best with inheritance tax (IHT) paperwork are those who plan ahead, say experts. We look at all documents you need to gather, regardless of whether you have an IHT bill to pay.

By Laura Miller Published