Britain mulls a wealth tax again – can it ever work?

A Covid-19-ravaged government needs to raise more revenue and some propose that a wealth tax could fit the bill. It’s unlikely to happen, but one way or another the rich face a squeeze, says Simon Wilson

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Why is this issue back in the news?

In a word, Covid-19. The pandemic has blasted a £400bn hole in the UK public finances and has hit the poor far harder than the rich. The best way of addressing these dual imbalances – according, that is, to a group of academics and think-tankers calling themselves the Wealth Tax Commission (WTC) – is a 5% levy on personal net wealth above £500,000, spread out over five years. Many countries are re-examining wealth taxes in the wake of the fiscal havoc wrought by Covid-19, but the only biggish economy to have rushed one onto the statute book is Argentina. Earlier this month the left-populist government announced a one-off “millionaires tax” on people with assets of more than 200m pesos (£1.8m). Under the scheme, which has been approved by Congress, wealthy citizens will pay a one-off levy of between 1% and 3% on net assets, with the aim of raising £2.7bn to help fund Covid-19 measures. In the UK by contrast, the WTC thinks the government could raise almost 100 times that – £260bn over five years.

What exactly is proposed?

The WTC is a group of academic economists from the London School of Economics and the University of Warwick, which formed earlier this year and has drawn on research and evidence from more than 50 tax experts from think tanks (including the Institute for Fiscal Studies), the OECD club of nations, as well as lawyers and policymakers. Its conclusion, in a paper published earlier this month, is that the UK should introduce a one-off 5% “Covid-19 recovery tax” on all personal wealth above £500,000, net of outstanding mortgage or other debt. That includes wealth held in housing (including a primary residence), pension schemes, businesses and financial assets such as shares and funds. Levied over five years, the WTC projects this would bring in £260bn from just over eight million people, or one in six households. In terms of revenue raised, that’s the equivalent (other things being equal) of a jump in the basic rate of income tax from 20p to 29p, or VAT from 20% to 26%.

Is that fair?

Not if you are someone (a reader of MoneyWeek, say) who has thriftily accumulated wealth over decades out of taxed income in order to avoid relying on the state in old age. Nor, say, if you are asset-rich, but retired or approaching retirement with a relatively low income. And there’s a particular unfairness when it comes to pensions. A wealth tax that included pension schemes, as proposed, would be doubly unfair to those of us with defined-contribution (DC) pensions, compared with those fortunate souls (overwhelmingly in the public sector) who have defined-benefit (DB) schemes. That is because, under the current tax rules governing lifetime allowances on pensions, the government assumes the value of a DB pension scheme is only 20 times the annual income paid out. So a £10,000 DB pension is valued for tax purposes at £200,000. In practice, however, a private sector DC pension would need to be far in excess of that to generate the same annual income (and potentially up to £1m depending on assumptions about annuity rates, inflation, and joint life requirements). In other words, a wealth tax on pensions would end up being wildly discriminatory against (overwhelmingly) private-sector workers.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Do wealth taxes work?

With all taxes, there’s a trade-off between revenues raised and entrepreneurial incentives blunted – or simply rich people leaving the country – at a cost to future overall growth. And the experience of almost all countries to have tried a wealth tax is that they prove counterproductive. Wealth taxes tend to encourage capital flight and discourage investment, and throw up distorting effects. For example, since debt is deductible, they tend to encourage the rich to borrow to invest in exempted asset classes (farmland or woodland, say), thus both shrinking the tax base and distorting the economy. For all these reasons, they are far less popular than they once were. Sweden abolished its wealth tax after nearly a century in 2007; France got rid of its version two years ago. However, four European countries still have versions of a wealth tax, namely Norway, Spain, Switzerland and Belgium.

Will it happen here?

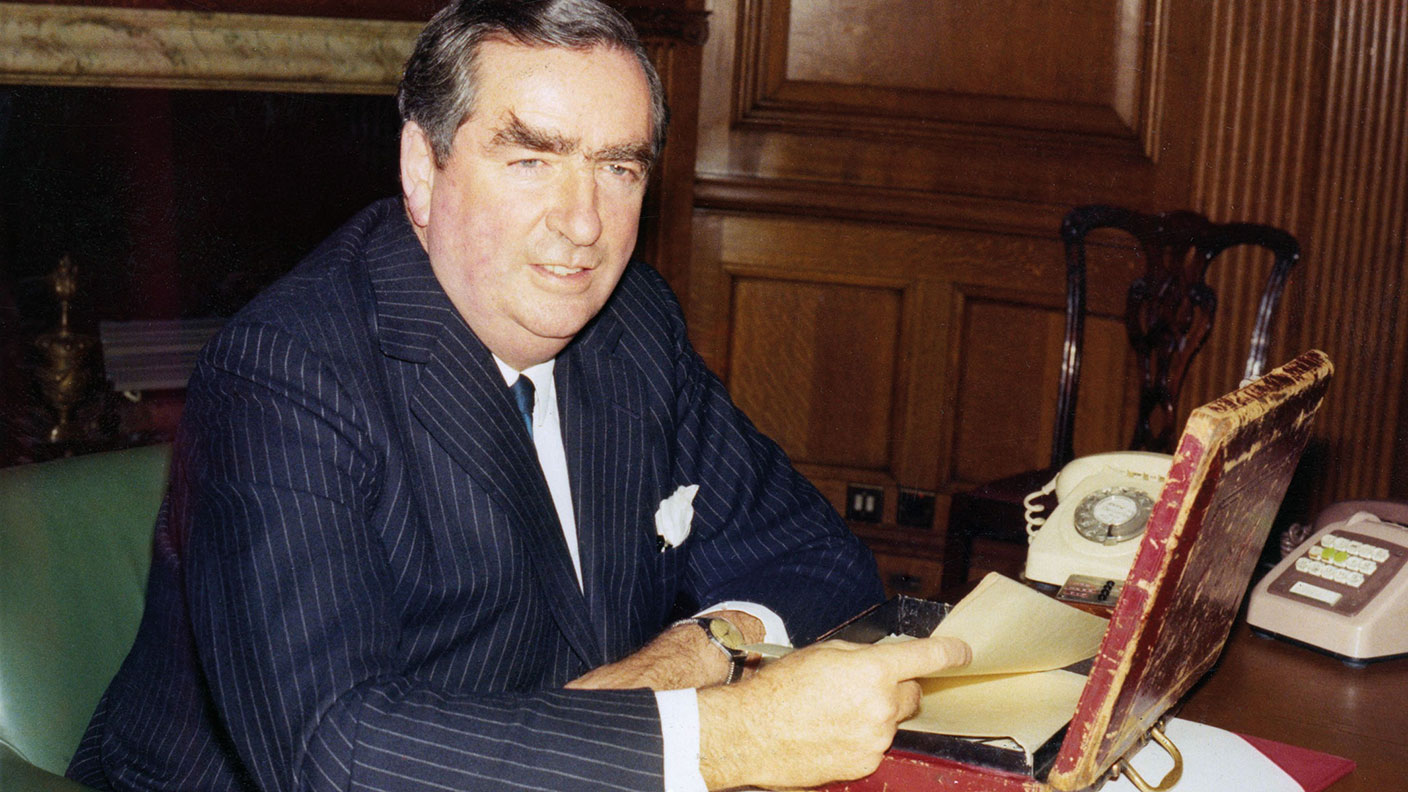

It’s unlikely, but it can’t be ruled out. Denis Healey, the Labour chancellor between 1974 and 1979, wrote in his memoirs: “We had committed ourselves to a Wealth Tax; but in five years I found it impossible to draft one which would yield enough revenue to be worth the administrative cost and political hassle”. That remains as good a summary as any and a wealth tax is not part of the current government’s plans. “I do not believe that now is the time, or ever would be the time, for a wealth tax,” said chancellor Rishi Sunak in July. Yet even so, argues economist Gus O’Donnell, the unpredictable politics of the post-Covid-19 era mean that nothing should be ruled out. And if the Conservatives are serious about sticking to their manifesto promises not to raise income tax, NICs or VAT, then at some point they’ll need to think seriously about new taxes.

What are the politics of this?

The political reality, says John Rentoul in The Independent, is that Sunak and Boris Johnson will be quite happy to see the idea of a wealth tax gain traction if it means a sigh of relief from wealthy Tory voters when none is ultimately forthcoming. That way, they get a bit of political cover to put up other taxes post-Covid-19 – which they surely will. In addition, it may be that the wealth-tax proposal “acts as a gateway to a return of the mansion tax” on higher-value homes, or to higher taxes on investment gains, or to big cuts in pensions tax relief. It may not come in the form of a “wealth tax”, but one way or another, wealthier Britons will soon be paying more.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?The Plan 2 student loan system is not only unfair, but introduces perverse incentives that act as a brake on growth and productivity. Change is overdue, says Simon Wilson

-

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?The Plan 2 student loan system is not only unfair, but introduces perverse incentives that act as a brake on growth and productivity. Change is overdue, says Simon Wilson

-

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategy

Why it might be time to switch your pension strategyYour pension strategy may need tweaking – with many pension experts now arguing that 75 should be the pivotal age in your retirement planning.

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher eraOpinion With the ISA under attack, the Labour government has now started to destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era, returning the economy to the dysfunctional 1970s

-

Investing in forestry: a tax-efficient way to grow your wealth

Investing in forestry: a tax-efficient way to grow your wealthRecord sums are pouring into forestry funds. It makes sense to join the rush, says David Prosser

-

'Expect more policy U-turns from Keir Starmer'

'Expect more policy U-turns from Keir Starmer'Opinion Keir Starmer’s government quickly changes its mind as soon as it runs into any opposition. It isn't hard to work out where the next U-turns will come from

-

Why pension transfers are so tricky

Why pension transfers are so trickyInvestors could lose out when they do a pension transfer, as the process is fraught with risk and requires advice, says David Prosser

-

Modern Monetary Theory and the return of magical thinking

Modern Monetary Theory and the return of magical thinkingThe Modern Monetary Theory is back in fashion again. How worried should we be?