Should investors worry about investment trust discounts?

Investment trusts tend to trade at discounts to their net asset value, but the advantages that come with them mean this matters less to some investors

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

One of the distinctive features of investment trusts is that they are closed-ended funds, and as such have a fixed number of shares. This means that investment trusts can trade at a discount to their net asset value (NAV).

By contrast. the number of available shares in other funds, like an open-ended investment company (OEIC) or an exchange-traded fund (ETF), increase and decrease in accordance with their NAV.

Investment trust discounts matter when trying to decide the best funds to invest in, because they impact the total return over time.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

“Discounts are double-edged – they can be an opportunity, or a frustration,” according to Nick Britton, research director at the Association of Investment Companies (AIC), an industry body that represents investment trusts.

Buying an investment trust at a discount to NAV offers, on paper, cheap exposure to its underlying assets compared to an alternative like an ETF or an open-ended fund. However, because the share price of any fund is a key component of its total returns over time, investment trust discounts can potentially reduce the value of their shareholders’ investment.

So there are clearly pros and cons to investment trust discounts, but how much of a difference do these make overall, and should investors worry about them?

What is an investment trust discount?

A discount is the difference between the total value of an investment trust’s shares and that of the assets it holds. It is expressed as a percentage of NAV.

If an investment trust trades at significantly less than its NAV, this is effectively the market expressing pessimism over the ability of its manager (investment trusts are always actively-managed funds).

As well as discounts, investment trusts can trade at a premium, meaning that they are valued at more than their NAV, because the market believes that the trust’s managers are skilled enough to outperform the wider market over time. 3i (LON:III), an investment trust that invests in private equity, currently trades at a premium of over 65%.

Premiums are less common than discounts, though. 3i is something of an exception, and in many respects behaves more like a corporate entity than an investment trust.

Excluding 3i (which is so large it would completely distort the data), the average investment trust discount as of 3 February was 14%, marking 29 consecutive months of double-figure discounts for this sample for the first time since Morningstar started tracking the data in 1996.

As Britton explains, there are rational reasons for investment trusts to trade at a discount to NAV. Closing a trust by selling all of its assets and returning these to shareholders would incur costs.

There is also a disconnect between the amount of potential demand for investment trusts compared to that for their underlying assets. A quarter of investment trust ownership comes from wealth managers, but in recent years these have trended towards convergence, increasing their size, the size of the portfolios they manage and, consequently, the size of the investment trust in which they can invest. Research from Winterflood Securities shows that the percentage of wealth managers that will invest in a trust with a market cap below £200 million has fallen rapidly in recent years.

“As the wealth managers and maybe other large investors don't want to buy those smaller trusts, they sell out of them and if they don't find other buyers, then the discount opens out,” Britton tells MoneyWeek.

Additionally, NAV is something of an estimate, particularly in the case of the kinds of illiquid assets that investment trusts are particularly suited to investing in.

“Valuing a private company is as much an art as a science,” says Britton. “With alternative assets, we're talking about a discount to an estimated asset value.”

Do discounts make investment trusts a bad investment?

It might seem that their tendency to trade at a discount to NAV makes investment trusts an inferior investment, compared to an alternative like an ETF that always trades in line with the value of its assets.

However, investment trusts offer certain advantages. For one thing, the mechanism through which ETFs and OEICs maintain their price correlation with their NAV involves constant buying and selling of their underlying assets as new shares are created and redeemed.

That requires highly liquid underlying assets, making it easier for investment trusts to invest in esoteric areas like private markets or property than other types of fund, which must be able to sell the assets they buy in a pinch if needed.

So investment trusts can offer individual investors a means to gain exposure to assets that they might not otherwise be able to own. Scottish Mortgage (LON:SMT), for example, holds some highly-valued technology start-ups like SpaceX (the fund’s top holding at time of writing) and ByteDance (the owner of TikTok), which aren’t publicly traded. Infrastructure-focused trusts like Greencoat UK Wind (LON:UKW) can invest in long-term projects that would be too illiquid for open-ended funds, without ever needing to worry about exiting their positions during the project’s lifetime.

Even if a hypothetical ETF had the same holdings as an investment trust, there are some other advantages to the closed-ended structure.

For example, unlike other types of fund, investment trusts can set aside 15% of their income annually. That allows them to build a reserve store of capital which, during poor years for the sectors they invest in, can be used to maintain steady income payments to their shareholders, giving them a smoother, more reliable income profile for investors than alternatives.

Investment trusts also have an independent management board, which acts in the interests of shareholders. That’s an extra layer of governance and oversight compared to what investors in open-ended funds or ETFs receive.

Finally, the managers of investment trusts can borrow to leverage their investments. This strategy – known as ‘gearing’ – isn’t as available to managers of open-ended funds, again due to the difficulties it could pose in disposing of assets when needed. Gearing can improve the returns of investment trusts during periods of positive performance, though it can also increase losses during downturns.

These factors can give investment trusts an edge over alternative products over the long term: research from the AIC and Morningstar shows that investment trusts provided greater total shareholder returns in the ten years to 31 January in 11 out of 15 sectors.

How do investment trust discounts affect returns?

Recently, New York hedge fund Saba Capital attempted to remove the board of seven UK investment trusts, largely driven by what it referred to as “persistent discounts”.

Britton points out that “if discounts are truly persistent, they make no difference to share price returns.

“Take an investment trust where the NAV grows at 7% a year over a ten-year period. Invest at a 20% discount and sell at a 20% discount, and your return is – you’ve guessed it – 7% a year.”

The reality is more complicated than that because investment trust discounts are dynamic, changing significantly over time, but the point is that a discount only hampers investors’ returns if it widens after they buy a fund. If it narrows, it could actually improve them.

This also only applies to NAV returns based on increasing share prices of the underlying assets. However, those assets may well also generate income, and if they do, a discount improves the yield (which is a percentage of the price of the asset) compared to buying the equivalent assets at NAV.

In Britton’s example, if the portfolio’s 7% gain comprises 4% in asset growth and 3% in yield, the 20% discount increases the yield to 3.75%, meaning the discounted trust would generate an annual return of 7.75% compared to an equivalent ETF that would return 7%.

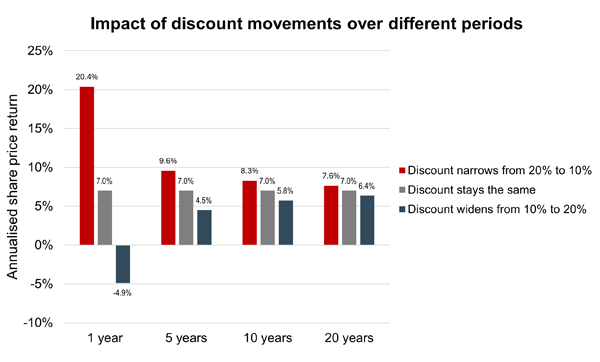

The impact of discount movements on total returns varies depending on the time horizon. The chart below looks at the annualised share price return over different time periods, under three different discount scenarios, for the same hypothetical trust with 7% annualised NAV growth:

Source: AIC. Assumes 7% NAV growth and straight-line discount movement over period.

Essentially, the longer the investment time horizon, the smaller the impact of discount movements on total returns.

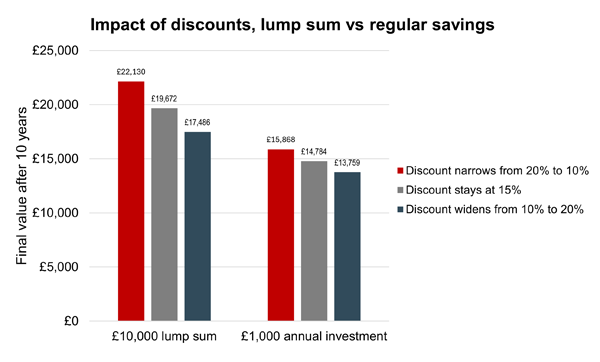

Additionally, regular savers will be impacted less by discounts than investors making a single large contribution, as this chart showing the difference between a £10,000 lump sum and ten annual investments of £1,000 shows:

Source: AIC. Assumes 7% NAV growth and straight-line discount movement over period.

As Britton explains, “none of this is to say that discounts don’t matter”. Record corporate activity last year, he says, is demonstrative of how seriously investment trust boards take discounts.

“But for investors, discounts matter more or less depending on your time horizon and style of investing. They matter much more to Saba than they do to, say, me – dutifully squirreling money away each month into my SIPP.”

Should you buy a discounted investment trust?

The upshot of all of this is that investment trust discounts offer some advantages and some disadvantages, and the relative weight of these will depend on the kind of investor that you are.

Over the long term, the negative aspects of discounts are diminished, and their positive attributes can shine, especially if investors are making regular investments. They also offer steady income compared to comparable open-ended funds or ETFs, often via assets that are harder for other types of fund to access.

So while discounts may mean that investment trusts aren’t the optimal vehicle for investors seeking short-term capital value growth, some of the advantages that come with them make them ideal options for investors seeking regular income over the long term.

All of that said, research by the AIC and Morningstar suggests that steeper investment trust discounts are correlated with higher annualised returns over the next five years.

“If you’re interested in the opportunity to bag a bargain, then you will be aware that now looks like a good time to go shopping,” says Britton.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Dan is a financial journalist who, prior to joining MoneyWeek, spent five years writing for OPTO, an investment magazine focused on growth and technology stocks, ETFs and thematic investing.

Before becoming a writer, Dan spent six years working in talent acquisition in the tech sector, including for credit scoring start-up ClearScore where he first developed an interest in personal finance.

Dan studied Social Anthropology and Management at Sidney Sussex College and the Judge Business School, Cambridge University. Outside finance, he also enjoys travel writing, and has edited two published travel books.

-

How should a good Catholic invest? Like the Vatican’s new stock index, it seems

How should a good Catholic invest? Like the Vatican’s new stock index, it seemsThe Vatican Bank has launched its first-ever stock index, championing companies that align with “Catholic principles”. But how well would it perform?

-

The most single-friendly areas to buy a property

The most single-friendly areas to buy a propertyThere can be a single premium when it comes to getting on the property ladder but Zoopla has identified parts of the UK that remain affordable if you aren’t coupled-up