Things are looking up for income investors as dividend payouts start to rise

UK dividend payouts are ready to grow again, but this crisis has shown why income investors must diversify overseas.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Things are finally looking up slightly for investors who rely on stocks for income. In the first three months of this year, UK dividends fell at their slowest annual rate since the pandemic began, down 26.7% excluding special dividends according to the latest quarterly figures from shareholder registrar Link. That still sounds painful, but the year-on-year figure disguises an encouraging trend: half of all listed companies resumed, maintained or increased their dividends between January and March, compared with just one third between October and December.

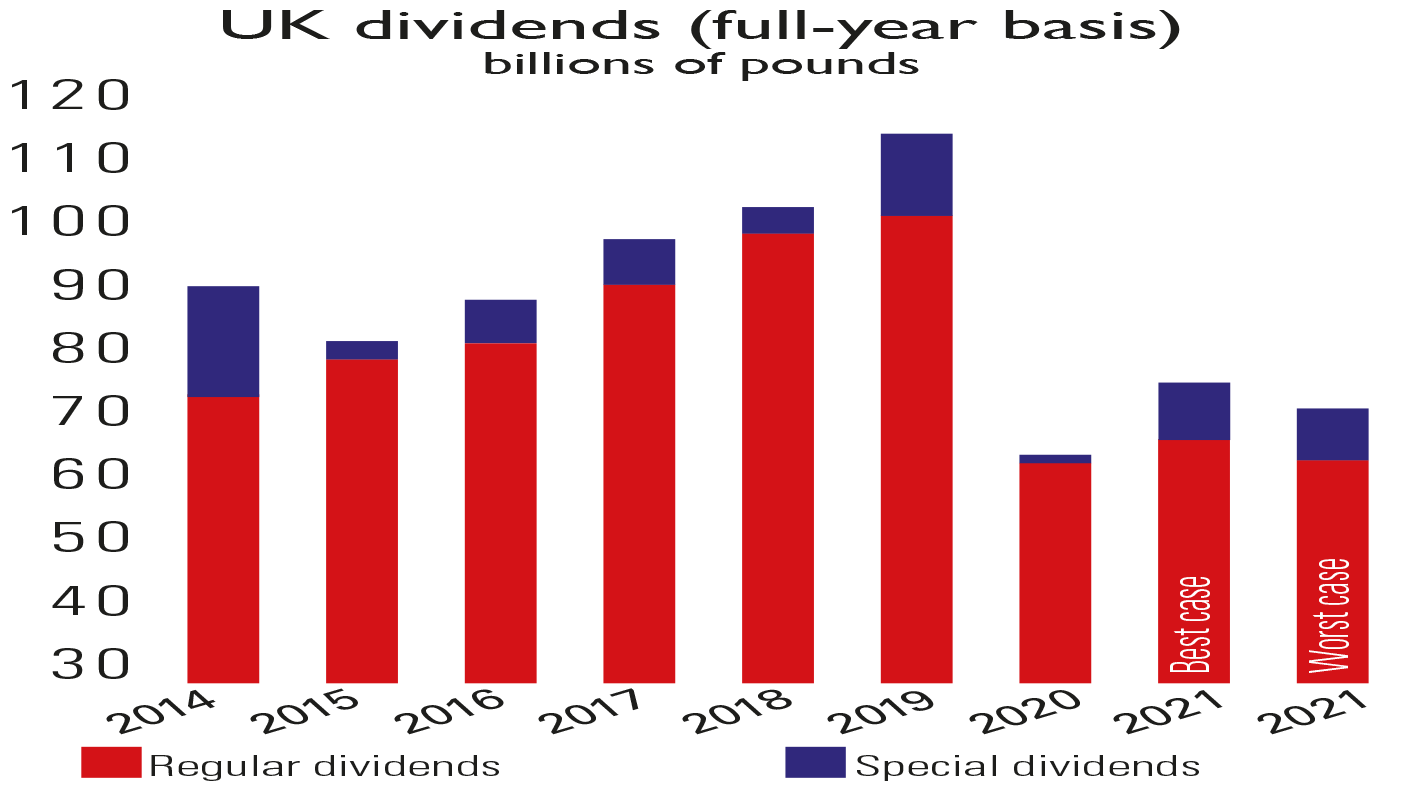

The bad news is that dividends fell an unprecedented 43.1% – including both regular and special dividends – in 2020. Even though payouts are recovering and we can expect a decent level of special dividends this year, Link projects that total UK dividends will rise between 11% and 17% in 2021. That will leave them between 33% and 37% below pre-pandemic levels and unlikely to regain previous highs until around 2025.

Investment trusts may yet need to cut

This will mean income portfolios and income funds that were too reliant on a small group of high-yielding stocks, such as banks, oil and gas, and miners (which made up three-fifths of cuts) are going to be paying a lower income for some time. Many income investment trusts are likely to be able to keep raising dividends due to their ability to draw on revenue reserves (see below). But if a trust has to do this too heavily for too long, it will ultimately affect future dividends or capital gains because they will be selling assets. Two trusts have already cut (Temple Bar and British & American) and two have announced plans to do so in 2021 (Edinburgh and Troy Income & Growth). If we face several years of weak dividends, others will have to consider it.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Go global for income

There was a way to avoid this: international diversification. British dividends were very hard hit in this crisis. Even European ones fell by less, down 31.5% before the effects of currencies and index changes, according to fund manger Janus Henderson, with half of that due to banks. Japanese dividends were slightly lower by 2.3% and US payouts were actually up by a similar amount. There were hits to favoured income stocks elsewhere – regulators in Australia and Singapore capped bank dividends – but a diversified global portfolio suffered much less.

Of course, UK dividend yields tended to be higher than the rest of the world, so overseas dividends looked less tempting – but the crisis proved that many of these yields were unsustainable. Investors should not forget this harsh lesson when payouts start to bounce back.

I wish I knew what a revenue reserve was, but I’m too embarrassed to ask

Many high-profile investment trusts have managed to raise their dividend every year for decades regardless of dividend cuts by companies. The main reason for this is that trusts, unlike open-ended investment funds, don’t have to distribute all the dividends they get each year. They can hold back up to 15% to build up a revenue reserve, which they can then draw on to maintain their own dividends in years when company payouts fall.

This can be useful for investors who prefer a steady income from their funds. You could do a similar thing with your own portfolio, by putting aside 10% or 15% of your dividend income to be drawn on only during market crises. However, avoiding dipping into that requires discipline, while having it out of reach inside an investment trust doesn’t present the same temptation.

That said, it is important to understand that a revenue reserve is not a sum of money separate from the trust’s portfolio, sitting in a bank account for emergencies. It is an accounting entry: the money will be invested alongside the trust’s other assets – in stocks, bonds or something else – on which the trust will hopefully be earning income and/or capital gains. Drawing on the reserve means selling assets. Typically the amount needed would be small, but if the trust had a large revenue reserve and had to draw on it for quite a while, the portfolio would shrink by a meaningful amount, which would cut future dividend income.

Following a change to tax laws in 2012, investment trusts are also allowed to pay dividends out of realised capital gains, known as the capital reserve. A few trusts now aim to pay out a flexible proportion of their value each year, regardless of whether that comes from capital or income. Drawing on capital to maintain a fixed dividend could make sense as a one-off in a crisis, but if a trust is forced to draw on revenue or capital repeatedly, the dividend is not sustainable.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?The Plan 2 student loan system is not only unfair, but introduces perverse incentives that act as a brake on growth and productivity. Change is overdue, says Simon Wilson

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser