The commodity-dependent slice of the economic pie is shrinking – here’s why

With the rise of the “intangible economy”, commodity companies’ share of the stockmarket’s capitalisation is at an all time low. Dominic Frisby explores where the sector goes from here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

So bitcoin’s at record highs, Tesla’s at record highs, the S&P 500’s at record highs – it’s as though they’re printing loads of money and it’s all going into speculative assets. It’s impossible to find anything of value, complain some, in such a frenzy of cheap money and speculation.

Ah, well wait a minute, say others, take a look at commodities. On a relative basis, they are as cheap as they have ever been, cheaper than they were in 2000, cheaper than they were in 1971. Buy commodities!

Are they right?

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Commodities have been relatively cheap for a long time

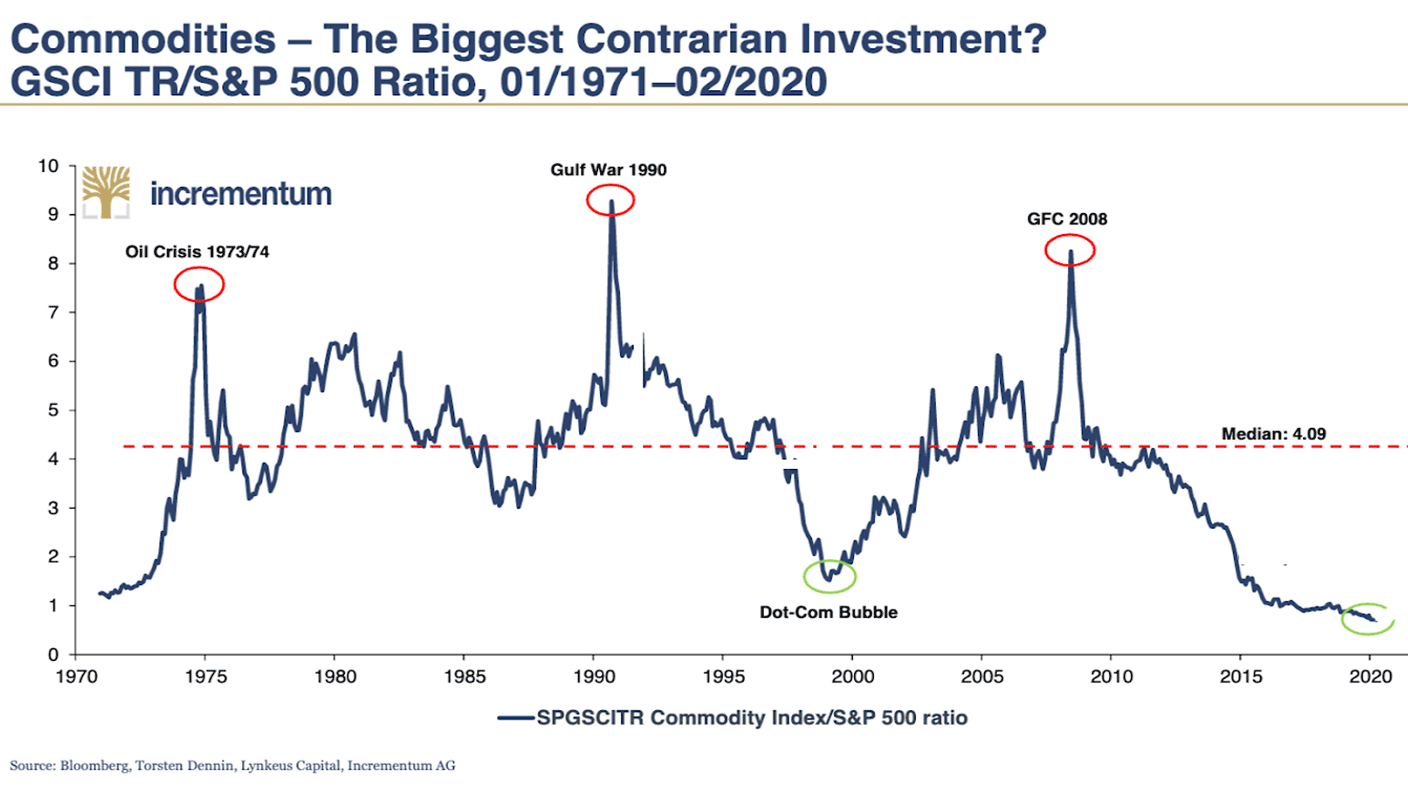

This – or a version of it – is the chart that usually gets cited. It shows the ratio of commodities prices (in the form of the Goldman Sachs Commodities Index) versus the S&P 500 (the US stockmarket, effectively). As you can see, it has never been so low.

There is only one way it can go from here, say the commodities bulls, and that is up. But then again they said the same thing in 2015. And in 2016. And in 2017. And in 2018. And in 2019. And here we are in 2020 and, on a relative basis, commodities are even cheaper than they were when Swiss investment firm Incrementum drew that chart at the beginning of the year.

What do I always say about new highs? New highs lead to more new highs – not always, but far more often than they don’t. The same goes for new lows: the most likely thing you will see after new lows is more new lows.

I’m bullish about oil by the way – I was buying last week. I’m bullish about gold (with some reservations after the run it’s already had this year). I’m bullish about platinum and base metals, and niche commodities such as helium. I don’t really know enough about the softs and the grains to offer any kind of opinion, but I can certainly recognise the relative value that certain commodities offer. But I still think that chart, the ratio between commodities and the S&P 500, can go lower – and here’s why.

The inexorable rise of the intangible economy

In 1990, the three biggest companies in Silicon Valley had a combined market cap of $36bn. Today, the three biggest – Facebook, Google, and Apple – have a combined market cap over $4trn. That is around 110 times bigger. Bitcoin, like Amazon and the iPhone, did not exist in 1990. Today, cryptocurrencies’ combined market cap is closing in on a trillion. What the past 30 years have seen is the incredible rise of the intangible economy. An entirely new economy, thanks largely to the internet, exists where it did not previously and it has the potential to grow yet further.

The physical economy has grown since 1990, but at nothing like the speed of the intangible economy. Take a look at any rich list; whereas in the 1970s that list would have been inhabited by people who made their money in oil, industry, mining or manufacturing, today’s super rich – certainly those under the age of 40 – almost all made their money in tech. Even real estate has fallen relatively.

What are the biggest companies on the S&P 500 by index weight? Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet and Facebook. Then it’s Berkshire Hathaway, and after that you get Procter & Gamble and Johnson & Johnson – “physical” companies of the old school. The biggest commodity company I could find was Exxon Mobil – all the way down in 40th.

The intangible economy is where the big money is. There’s a very simple reason for this: scalability. I can design a fantastic piece of software, upload it to the app store and it can be downloaded a million or a billion times. Digital means something is endlessly and instantly copy-able. But if I want to build a mine, it is going to take me ten years to get from discovery to production (and that’s assuming I actually make a discovery. Most don’t). The time and distance between investment and profit is so great that many don’t bother. They want the faster returns you get in tech, and so tech attracts more investment capital – and the cycle spirals.

There’s the issue of employees. In 1990 the three largest companies in Silicon Valley employed over a million people. Today’s largest employ less than 25% of that. Look at something like bitcoin and cryptocurrency – there is an entirely new digital economy there with extraordinary growth potential.

We’ll still need commodities – of course we will. All those computers are made out of metal, after all. They have to be shipped around the world and that requires oil. You can still make a great deal of money investing in these sectors. But with the rise of these new digital economics in intangible worlds that didn’t previously exist, commodities are never going to occupy such a large part of the global economy. That doesn’t mean they can’t increase in value. They can. But tech made the pie that much bigger, so the relative slice that is commodities inevitably gets smaller.

That’s why that ratio chart can still go lower and why it will take something extraordinary like war, hyperinflation or decades of underinvestment to ever lift that chart back to the highs we saw in 1974, 1990 or 2008.

Daylight Robbery – How Tax Shaped The Past And Will Change The Future is now out in paperback at Amazon and all good bookstores with the audiobook, read by Dominic, on Audible and elsewhere.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge