People

The latest news, updates and opinions on People from the expert team here at MoneyWeek

Explore People

-

The downfall of Peter Mandelson

Peter Mandelson is used to penning resignation statements, but his latest might well be his last. He might even face time in prison.

By Jane Lewis Published

-

What is Donald Trump’s net worth?

Donald Trump’s net worth makes him the richest-ever US president, and the only billionaire to live in the White House. We take a deep dive into his fortunes

By Oojal Dhanjal Last updated

-

What is Anant Ambani’s net worth?

Anant Ambani is the son of Asia’s richest man. His grand wedding garnered worldwide attention in 2024. What is his net worth?

By Oojal Dhanjal Last updated

-

What is Elon Musk's net worth?

Elon Musk is the richest person in the world and close to becoming the first-ever trillionaire. How did the Tesla and SpaceX founder make his fortune?

By Oojal Dhanjal Last updated

-

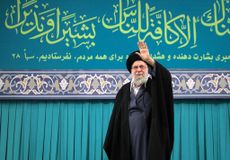

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: Iran’s underestimated chief cleric

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is the Iranian regime’s great survivor portraying himself as a humble religious man while presiding over an international business empire

By Jane Lewis Published

-

Long live Dollyism! Why Dolly Parton is an example to us all

Dolly Parton has a good brain for business and a talent for avoiding politics and navigating the culture wars. We could do worse than follow her example

By Jane Lewis Published

-

Michael Moritz: The richest Welshman to walk the Earth

Michael Moritz started out as a journalist before catching the eye of a Silicon Valley titan. He finds Donald Trump to be “an absurd buffoon”

By Jane Lewis Published

-

What is David Beckham's net worth?

David Beckham’s net worth comes from his illustrious football career and high-profile endorsement deals, while Victoria has earned millions through fashion

By Oojal Dhanjal Last updated

-

David Zaslav, Hollywood’s anti-hero dealmaker

Warner Bros’ boss David Zaslav is embroiled in a fight over the future of the studio that he took control of in 2022. There are many plot twists yet to come

By Jane Lewis Published