The Fed springs a surprise on investors – are there more to come?

The US Federal Reserve has turned more aggressive than expected on inflation, driving fears of an early interest-rate rise. John Stepek looks at what it means for the markets and for you.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Last night, the US Federal Reserve sprung a surprise on markets.

It was more aggressive about inflation than anyone expected.

At this rate, it thinks we might see some interest rate rises by the end of 2023.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

If you’re wondering why that was enough to give investors an unwelcome dose of reality, then read on.

Why markets have become much more sensitive to the Fed’s every motion

Before the modern money-printing era, central bank decisions used to be quite simple things to analyse.

The central bank – be it the Federal Reserve or the Bank of England – would raise interest rates, cut interest rates, or leave them where they were.

If you were looking for a bit more nuance, you might look at how many people voted in line with the decision, but even then, the level of dissent varied widely – you often got dissenters on the Bank of England, whereas almost every Fed decision was unanimous.

That was it: one big number to watch, and the occasional twitch of the eyebrow to add a wee thrill for the forecasters.

Today, analysing central bank decisions is a lot more complicated. It’s a mini-cottage industry all to itself. It involves running entire statements through a word processor to pick up on changes to the placement of commas and minor syntax shifts.

It means trying to work out what’s happening with a handful of money-printing programmes and bond-market plumbing issues.

And while interest rates themselves don’t matter as much, because they’re stuck at zero and – it’s assumed – will be for some time, what does matter is whether the central bank is thinking about raising rates at some point in the future.

This in turn means – in the case of the Fed, which like it or not, is the most important central bank – decoding “dot plots” which show exactly where each individual member thinks interest rates will be by a given year.

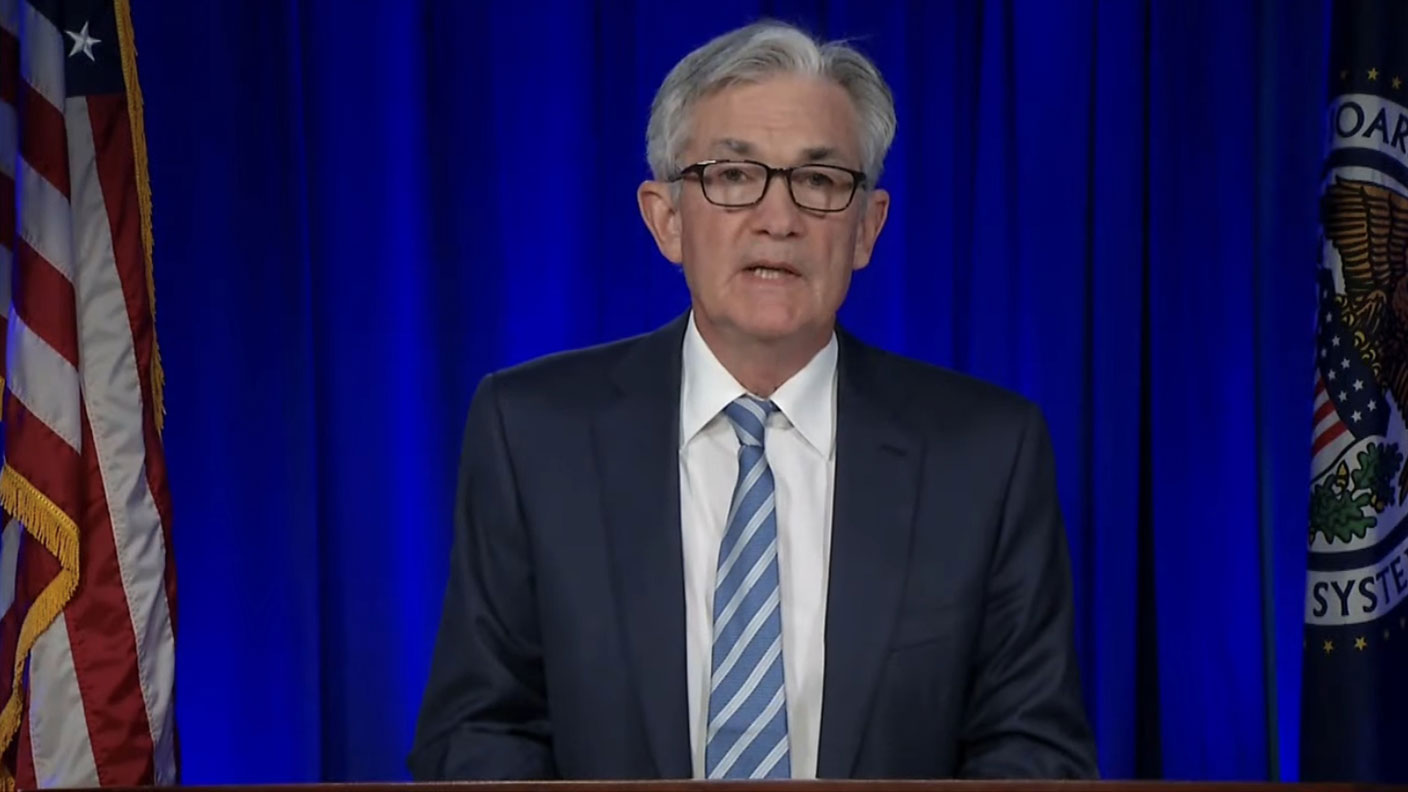

And it means the Fed boss – currently Jerome Powell, but his predecessors have had to learn this too – has to speak very carefully indeed at the post-match press conferences.

We’ve highlighted the absurdity of all of this before, but it really is extraordinary. The point of free markets is to allocate capital efficiently. Yet the whole edifice comes to a nail-biting pause every six weeks or so, and can abruptly shift direction based on a stray comma.

Why the increased sensitivity? A lot of it is a side-effect of zero or near-zero interest rates. When rates are at 5%, 0.25% is a small move. When rates are at 0.1%, 0.25% is a very big move indeed.

If you’re struggling to understand this, then imagine an interest-only mortgage. If the interest rate goes up from 5% to 5.25% – it doesn’t matter. Almost regardless of how recklessly you’ve borrowed, that move won’t ruin your finances. At £500 a month, your payment would rise to £525.

If you borrowed at 0.1% however (let’s imagine you’re in Denmark, where they even have negative rate home loans for some), and the interest rate goes up to 0.25%, your monthly payment will more than double. So you’d go from paying £500 to about £1,250. (This is a heavily stylised example, but you take the point.)

That’ll ruin you. And that’ll have you watching your bank manager like a hawk.

The most obvious change is in the US dollar

Anyway – so what happened yesterday is that the Fed did a few nudges and winks that turned out to be more hawkish than everyone (yours truly very much included) had expected.

The “dot plot” shows that more Fed members expect rates to have risen. As Helen Thomas of Blonde Money points out, in March just seven Fed members expected at least one rate hike in 2023. Now 13 do. And overall they expect two rate hikes, not just one.

As I said, this is technically a tiny shift. But if markets have been betting on “lower for longer” and “liquidity to the gunwales” then they’re not going to be terribly happy about hearing even a modicum of doubt introduced there.

As Thomas also points out, this rather goes against what the Fed has been trying to say publicly, which is “we don’t care about inflation just now because a) it’s transitory and b) jobs are more important”.

Now it feels to markets as though the Fed is wavering. Either they think inflation is going to be more persistent, or growth stronger.

What does this all mean in practice for you as an investor?

Hands up, as I wrote on Monday, I thought the Fed would err on the side of dovishness. It didn’t.

As a result, the US dollar has shot up. A stronger US dollar is (in this context at least) is a warning to asset markets. The world’s most important currency is getting stronger, which in effect means that global monetary policy is a little tighter.

We haven’t seen massive fallout yet. As Dominic noted yesterday, some froth has been coming off commodity markets and precious metals took a hit last night. As for wider markets – the Nasdaq slipped (it’s arguably the most interest-rate sensitive market) but the FTSE 100 is little changed (it helps that the pound has dived against the dollar, which tends to prop up the FTSE 100 as it has a lot of dollar-earning stocks).

What I’m looking for now is to see the Fed walking this back. Jerome Powell remained at pains to emphasise “outcomes” rather than forecasts, and pointed out that the dot plot is “not a plan”. He also said that they haven’t discussed reducing money printing in detail: “You can think of this meeting that we had as the ‘talking about talking about meeting’... we’re still a ways from our goal of substantial progress.”

In short, this was a shake for markets. A reminder not to bet the house on one outcome. So far it seems to me that the underlying “let’s not be too hasty” message is still intact.

But markets won’t take that for granted any more. And that could mean turbulence especially in the thinly-traded summer months.

You don’t need to make any big changes to your strategy. You might just need to be prepared for more ups and downs up ahead.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

UK unemployment hits highest level since 2021 – will interest rate cuts follow?

UK unemployment hits highest level since 2021 – will interest rate cuts follow?UK unemployment reached its highest rate in almost five years by the end of 2025. Is AI to blame and will the Bank of England step in with an interest rate cut in March?

-

Did UK inflation fall in January?

Did UK inflation fall in January?After rising in December, analysts expect the next round of UK inflation data to show that disinflation returned in January

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'Opinion Donald Trump's actions against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell will likely stoke rising prices. Investors should prepare for the worst, says Matthew Lynn

-

'Governments are launching an assault on the independence of central banks'

'Governments are launching an assault on the independence of central banks'Opinion Say goodbye to the era of central bank orthodoxy and hello to the new era of central bank dependency, says Jeremy McKeown

-

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?It seems clear that Trump would like to sack Jerome Powell if he could only find a constitutional cause. Why, and what would it mean for financial markets?

-

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?Donald Trump has been vocal in his criticism of Jerome "Jay" Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve. What do his threats to fire him mean for markets and investors?

-

Do we need central banks, or is it time to privatise money?

Do we need central banks, or is it time to privatise money?Analysis Free banking is one alternative to central banks, but would switching to a radical new system be worth the risk?

-

Will turmoil in the Middle East trigger inflation?

Will turmoil in the Middle East trigger inflation?The risk of an escalating Middle East crisis continues to rise. Markets appear to be dismissing the prospect. Here's how investors can protect themselves.