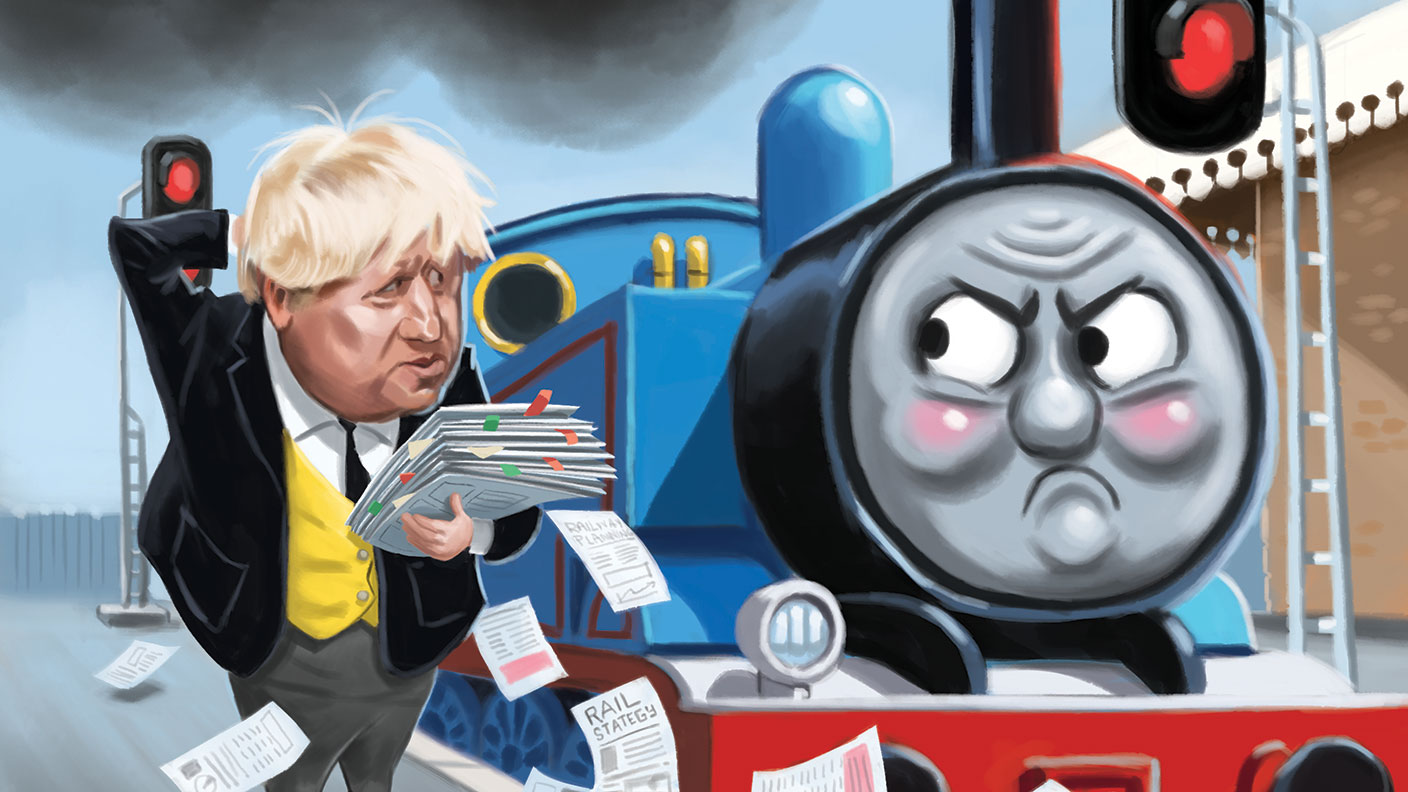

Backtracking on HS2: the state of high-speed rail in the UK

The government has found a reverse gear on the controversial high-speed rail project. But does backing out now make sense?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

What’s happened?

After years of reassurances and manifesto pledges that High Speed 2 would be built in full – including the arm from Birmingham to Yorkshire as well as the one to Manchester – the current government has backtracked. Instead of heading to Leeds, there will be a much shorter spur north-east from Birmingham to East Midlands Parkway, a new station serving the region around Leicester, Derby and Nottingham. From there, high-speed trains will slow down onto existing lines.

If HS2 has always been a white elephant, quipped the Tory MP Sir Edward Leigh, then it is now “missing a leg”. In addition, Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR), the proposed high-speed link connecting Liverpool to Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield, Hull and ultimately Newcastle, has also been scrapped. In its place upgrades to existing lines and full electrification of the Midland Main Line from London to Sheffield is promised. The government styles this as its “Integrated Rail Plan”.

Is HS2 a white elephant?

It’s certainly a very expensive way of achieving very little. England is a small country where the distances involved are short and the time savings minimal, and business travellers (the core market) can already work on trains anyway. The benefits in terms of “levelling up” Britain’s economic geography have always been overstated, since evidence (from France and Spain, for example) is that the dominant hub city (here, London) benefits far more from the high-speed links than the regional city. And to date the execution has been poor.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Last year’s Oakervee review, which convinced Johnson to press ahead, found that the economic benefits remained unclear, and that HS2, especially the phase one construction team, lacked “the level of control and management of the construction normally associated with big projects”. The National Audit Office judged that it’s impossible to predict the final cost; that the latest 2040 target for completion probably won’t be met; and that HS2 and the government had “not adequately managed risks to taxpayers’ money”.

So downsizing it is a good idea?

Shorn of its Leeds arm, HS2 “makes even less sense”, says Liam Halligan in The Daily Telegraph. The reasons the project is going ahead anyway are “inertia, the lobbying power of engineering conglomerates and property developers, and broader metropolitan bias”.

But the really “odd” part of the government’s latest plan is the scrapping of NPR. The high-speed trans-Pennine route was regarded by many voters and political leaders in the north as the centrepiece of the Conservatives’ levelling-up agenda. Moreover, “countless independent studies showing that the productivity gains of NPR far outstrip those of HS2”, says Halligan.

What’s the government’s rationale?

It’s partly about money, and partly about electoral politics. To see which department – Transport or Treasury – was in overall charge of last week’s Integrated Rail Plan, says Dominic O’Connell in The Times, take a look at page 24 of the document. “Commitments will be made only to progress individual schemes up to the next stage of development, subject to a review of their readiness.” In other words: if the costs start to run away, and threaten to breach the overall cap of 3% of GDP on capital spending, then think again.

However, the overall projected cost saving is not enormous: the government says its new plan (the “biggest transport investment programme in a century”) will cost £96bn, compared with £110bn, the previous latest estimate of HS2’s overall cost.

What about the politics?

The government hopes that voters in their northern “Red Wall” seats will be grateful for the absence of big construction disruption in recently won Tory seats such as Rother Valley, Bolsover and Ashfield – and also faster visible results in terms of upgrades to the lines between the East Midlands, Leeds and Manchester.

On the latter, they are likely to be disappointed, says Stephen Bush in the New Statesman. For one thing, the promised benefits will still take years to materialise, meaning that the dominant narrative will remain that the Tories have “betrayed the north” by reneging on their promises.

Second, due to capacity constraints, those promised improvements for local rail are unlikely to materialise without committing to a segregated service for high-speed and inter-city trains. Thus, the Tories may come to see the cancellation of the Leeds arm as a false economy and bad politics. Indeed, last week George Osborne predicted that Johnson would U-turn on his U-turn in the run-up to the next election.

Labour has already committed to reinstating the full HS2 eastern route, and the whole of NPR, and the Tories will be forced to match them, reckons the Tory ex-chancellor.

So the cancellation is a mistake?

The problem is that what the government has announced is not “a proper alternative”, says The Times. The crucial issue – which HS2’s proponents have always been bad at explaining – is not speed but capacity.

“Britain’s main rail arteries, especially the east and west coast main lines, are already operating at maximum capacity, with no room for growth.” HS2 had a crucial role in freeing up capacity to enable more standard-speed services and freight. Now that we’ve started, it makes sense for the full HS2 network to be built.

But it’s not about HS2, says John Ashmore on CapX. It’s about the inability of the British state to complete big strategic projects in a timely manner. Crossrail is years late and over budget and our aviation capacity is “full-to-bursting”. Add in the government’s net-zero commitments and “the can-kicking and foot-dragging that have long characterised our infrastructure policy only looks like getting worse”.

All of which adds up to a country that, HS2 or not, “risks being stuck in the slow lane for years to come”.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

The UK regions with the highest proportion of homes above the inheritance tax threshold

The UK regions with the highest proportion of homes above the inheritance tax thresholdHigh house prices are pushing more families into the inheritance tax trap across the country

-

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek Talks

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek TalksPodcast Clare Francis, savings and investments director at Barclays, speaks about money and mental health, why you should start investing, and how to build long-term financial resilience.

-

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’Opinion UK small-cap stocks could be set for a multi-year bull market, with recent strong performance outstripping the large-cap indices

-

The scourge of youth unemployment in Britain

The scourge of youth unemployment in BritainYouth unemployment in Britain is the worst it’s been for more than a decade. Something dramatic seems to have changed in the labour markets. What is it?

-

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growth

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growthGDP doesn’t measure what we should care about, say critics. Is that true?

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton