Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

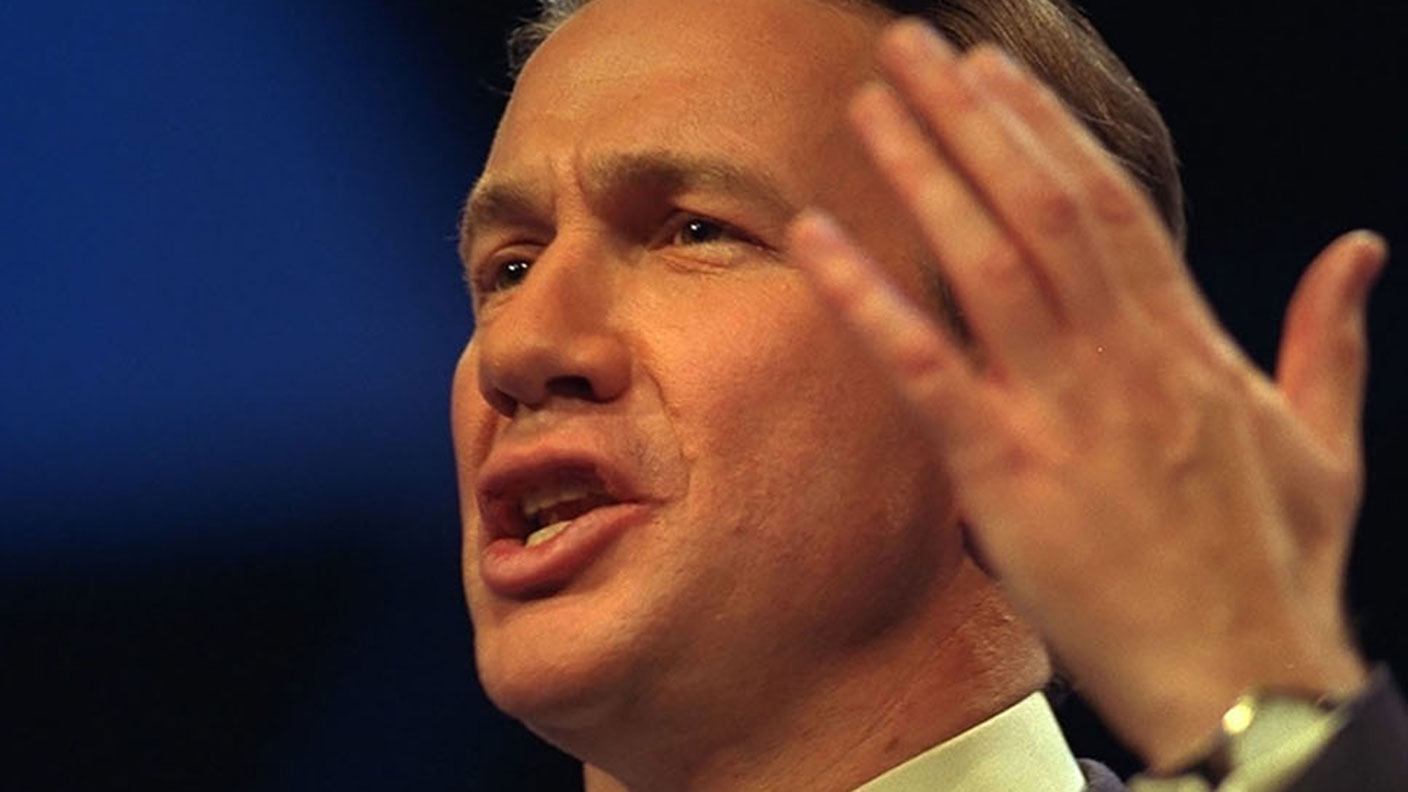

Not long after the 1992 election, I heard Michael Portillo speak at an investment conference in the City. Britain was then emerging from a recession, but the finances of John Major’s government were in massive deficit. Portillo’s message was clear. As Labour retreated from its capture by the Left in the early 1980s, the policy differences between Labour and the Conservatives, he predicted, would steadily narrow. But on one issue, taxation, there would continue to be “clear blue water” between the parties. If, however, the chancellor used tax increases to narrow the fiscal deficit, the Conservatives would be defeated at the next election and remain out of power for a long time.

Whereas Nigel Lawson had taken pride as chancellor in abolishing a tax in every budget, his successors adopted the opposite policy, perhaps egged on by Treasury officials. In 1993, Norman Lamont levied VAT at the rate of 8% on domestic fuel as well as freezing tax allowances and raising excise duties in real terms. Later that year his successor, Ken Clarke, introduced taxes on insurance and air travel and continued to raise inflation-adjusted duties.

Abolishing boom and bust

The combination of tax increases, spending restraint and economic growth eliminated the budget deficit as planned. But, as Portillo had predicted, the government got no thanks from voters at the 1997 election. It remained out of office for 13 years and could only govern in coalition for another five. Labour’s chancellor, Gordon Brown, was initially “prudent for a purpose”, but, believing he had abolished boom and bust, then threw caution to the wind.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In the 2008 financial bust, the government deficit again went through the roof. All that had been achieved by the fiscal rectitude of the Major government was to enable its successor to be reckless. When Labour lost the 2010 election, Liam Byrne, Brown’s number two at the Treasury, left a note to his successor saying “there is no money left”. It’s not surprising that the initial enthusiasm of the coalition government for cutting the deficit soon wilted or that the subsequent Conservative government was no more keen. The lesson that electorates don’t reward fiscal rectitude – yet it is a gift to the opposition – seemed to have been learned.

But has it really? The pandemic has seen government revenues plunge and expenditure soar so that public-sector debt is now over 100% of GDP. With public transport and many local councils bankrupt without bailouts and monthly deficits continuing, Treasury officials, egged on by the media, the opposition and, surprisingly, many Conservative backbenchers with impaired memories, are again calling for tax increases. The focus is on “the rich”, by which most people mean “someone other than me”, but taxes on the rich or well-paid never generate as much revenue as expected, if any. Such tax increases would inevitably be extended to everyone.

The obvious problem with this strategy is that it would impair economic growth and growth is always the principal driver of deficit reduction. The second problem is that taxes are already high; for example, the top marginal rate of tax, applied to annual earnings between £100,000 and £125,000, is 62%. The third problem is that it would be electoral suicide for the government.

Buying time

There are no good answers, but with the cost of government borrowing down to derisory levels, there is no urgent need to take action on the deficit. It may seem to us that the government is spending like a drunken sailor and that a good part of the money has been wasted, but governments in the EU, Japan and the US have been far more extravagant. In time, economic recovery will increase revenues, limit spending and reduce the ratio of debt to GDP, provided that the rebound is encouraged.

There is action the government could take to reduce the current and future deficits. The collapse in rail traffic shows HS2 to be a grotesque waste of money and replacing student loans with a graduate tax would increase revenues, reduce the debt burden on graduates and be fairer. A trick was missed when some of the benefit to petrol prices from the fall in the oil price was not absorbed in petrol duty. Unfortunately, though, there are also taxes that need cutting: the rate of national insurance should be cut from 12% to 10% and levied above £12,500 (the income tax allowance) rather than £7,500. The top marginal rate of income tax is too high.

With such a strategy, the government might have nine years to get its finances in order, rather than four and a half. If only Portillo could take some time off his rail travels to repeat the powerfully vindicated warning he gave nearly 30 years ago.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.

-

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?Graduates are complaining about their levels of student debt so should wealthy parents be helping them avoid student loans?

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growth

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growthGDP doesn’t measure what we should care about, say critics. Is that true?

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?