How to buy low and sell high

Once you’ve got an investment pot together, periodically rebalancing your portfolio keeps your money working for you by buying cheap assets and selling those that have become expensive. Phil Oakley explains how it’s done.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Don't put all your eggs in one basket. It's an ancient piece of investment advice, and one that everyone should follow.

We've already looked at asset allocation and diversification in this series (which is what the City experts call not putting all your eggs in one basket').

But once you've put your investment portfolio together, how do you look after it and make sure it keeps doing what it's supposed to be doing?

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

They key is to regularly rebalance' your portfolio.

What is rebalancing?

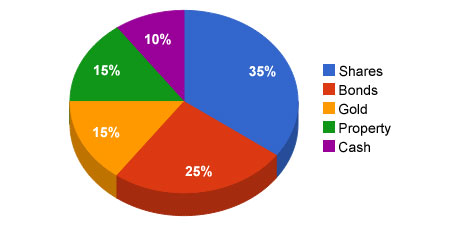

By dividing your pot up like this, and putting different amounts into each asset, you hope that the portfolio will meet your financial goals.

The trouble is, the prices of shares, bonds and other assets tend to move around - sometimes very significantly. Some assets go up in price, while others go down. After a while, your investment fund could look quite different to what you started off with.

So rebalancing simply involves doing some buying and selling to get your money back to your target allocations. Say gold had gone up in price and now took up 20% of your portfolio, while property had fallen to 10%; you would sell some gold to get back to 15% and use the proceeds to buy property.

Why rebalancing matters

One of the main problems with investing is that people become too emotional about it. Human beings have the tendency to chase the latest hot investment while selling out of stuff that has gone down in price - the exact opposite of what they should do.

If you think about this in terms of a portfolio, the assets that do well become a bigger part of the portfolio while those that do badly become a smaller part. Let's say that you don't rebalance your portfolio and shares experience a bull market and go up in value a lot. At the time, you'll probably think it's great, as your portfolio will probably go up in value too. But your portfolio would have become more risky.

If shares had become 50% of your portfolio at the top of a bull market and then crashed by 50% (which has been known to happen) your fund would have lost a quarter of its value (50% of 50%).

Now don't get me wrong - it would still have lost 17.5% at a 35% allocation - but by regular rebalancing you could have limited the damage by continually selling shares as they went up in price and reinvesting your money into assets that had performed poorly. (In the late 1990's equity bull market, selling shares and buying gold would have worked well, for example).

Essentially, rebalancing allows you to buy low and sell high - a practice that tends to make you money in the long run.

But does rebalancing work?

David Swensen - who runs Yale University's endowment fund - is a big believer of rebalancing. In his book Unconventional Success, he cites a study by investment company TIAA-CREF which compared two investment approaches.

In one case, a portfolio with 49% shares and 51% bonds was rebalanced every year. Another portfolio started off from the same allocation but was left to wander with the markets. Between 1992 and 2002, the rebalanced portfolio made more money, despite the other fund having 70% of its money in shares in 2000.

US financial advisor Harry Browne advocated an investment strategy of equally dividing your money between shares, cash, bonds and gold. According to authors Craig Rowland and JM Lawson, between 1972 and 2011 a portfolio like this, rebalanced annually, delivered annual returns of 9.5% compared to 8.8% from the one that was left alone.

That might not seem much of a difference. But over 39 years, the rebalanced portfolio only lost money in four years with a biggest annual loss of 4.9%. The other portfolio lost money in 11 years with a biggest loss of 21.6% - which portfolio would you rather own?

How often should I rebalance?

One option is to rebalance once a year. Alternatively, you could rebalance when an allocation is more than 5-10% above or below where it should be. Rebalancing is best done within tax free accounts such as Isas or Sipps as selling assets that have gone up a lot could trigger capital gains tax on large portfolios.

What about investing new money? The best option here is to invest it in cash or the worst-performing asset in your portfolio.

And how about dividend reinvestment? We like the idea of reinvesting dividends and compounding returns. But only if you are reinvesting into an asset that is not overpriced. This is easily done if you set up your investment account to automatically reinvest dividends. It might be better to pay them into your cash account instead and reinvest elsewhere.

Successful investing is never going to be easy, but rebalancing can certainly keep you moving in the right direction.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Phil spent 13 years as an investment analyst for both stockbroking and fund management companies.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.