Four good reasons to invest in Asia - and why growth isn't one of them

Growth can be irresistible to investors. And there's little doubt that Asian economies will grow much faster than those in the West. But growth by itself is not enough, says Cris Sholto Heaton. Here, he gives four much better reasons for investing in Asia.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Growth is the best way to lure investors. That's why the fund industry baits its China and India funds with promises of economies that can grow at 10% a year, even as the West struggles in its post-crisis malaise.

But it's not that simple. Growth by itself is not enough. And as usual when selling a hot story, salesmen tend to gloss over what really makes the difference.

The key to good returns is something much less exciting: value. That's just as true if you're buying an index tracker as when you're looking at individual stocks. Forgetting that and getting hooked on the growth story alone could be a painful mistake

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

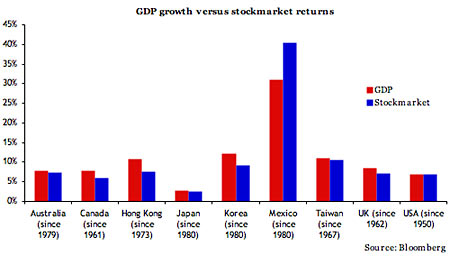

Strong growth doesn't always mean good returns

We might expect the value of stocks to grow in line with the economy. And the chart below suggests that over a long enough period this is true: the average growth rate of nominal GDP and the annualised increase in the stock market seem to be reasonably close on average for those countries for which I could easily get consistent data stretching back 30-60 years.

Figure 1: Long-term nominal GDP growth and stockmarket returns, selected markets

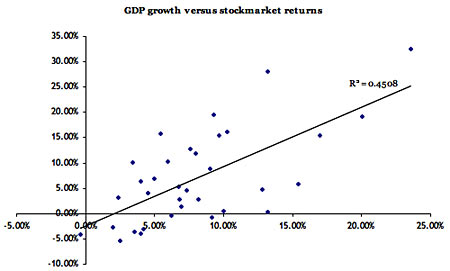

But that's only looking at the long term. Over shorter periods, stock market performance and GDP growth can diverge quite drastically. On the chart below, I've broken down the data into successive ten-year periods (eg 1989-1999, 1999-2009 and so on) and plotted the growth rate of stocks against the growth of the economy (some countries have several points, some have just a couple again, it depends how good the data is).

Figure 2. Correlation between nominal GDP growth and stockmarket returns, ten-year intervals

As you can see, there is a very loose and weak positive relationship (the R-squared measure of correlation is a low 0.45), but the dispersion is huge. And there are plenty of cases like Taiwan from 1989 to 1999, where growth of 9% was rewarded with stockmarket returns of -1%.

That's a fairly random sample of countries, covering only the past few decades. I wouldn't want to claim that it's a thorough study. But it is pretty much what we'd expect, because returns don't just depend on growth where you begin is even more important.

Why valuations matter

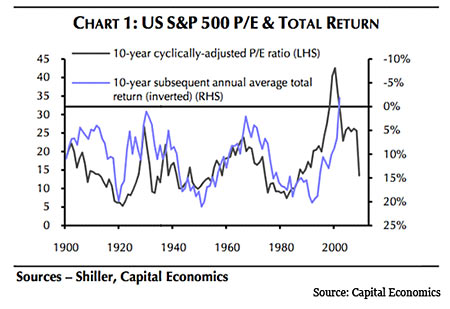

You may recognise the chart below from previous emails: it shows ten-year subsequent total returns for the S&P 500 (inverted) versus the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio (i.e. the current price of the stock market divided by the average inflation-adjusted earnings over the previous ten years this attempts to smooth out short-term profit fluctuations and value stocks on a through-cycle basis). As you can see, the two have had a close relationship in the past. (I'm using the US here because the long-term data doesn't exist for almost all other markets.)

Figure 3. US S&P500 cyclically adjusted p/e versus subsequent total return

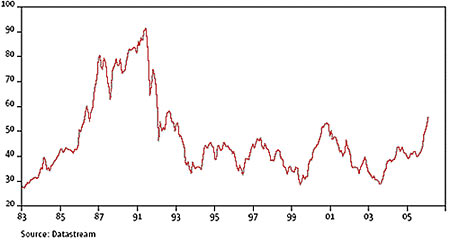

Times when investors have paid too much for shares have been followed by poor returns, regardless of whether it's followed by strong growth in the economy or not. It hasn't been two decades of low growth that have produced terrible equity returns in Japan since 1989 it was the fact that back then the market traded on an cyclically adjusted p/e of around 80 times earnings, as the chart below from CLSA's Russell Napier shows.

Figure 4. Cyclically adjusted p/e for Japan

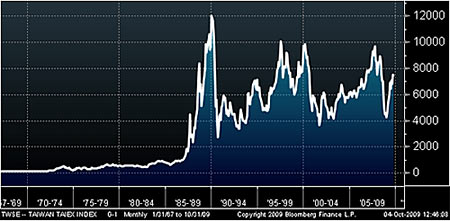

Meanwhile, Taiwan's staggering melt-up in the late eighties peaked at 160 times operating earnings, according to Steven Champion in The Great Taiwan Bubble. One sleepy business bank traded at a valuation that implied the whole GDP of the world would be passing through its books within the next 13 years.

Figure 5. Taiwan Taiex index

Obviously, valuations like these are extreme events but investors should always be asking themselves whether market valuations imply a realistic expectation of future earnings growth. In the long run, corporate profits overall can't grow faster than the economy. If they exceed the GDP growth rate, the share of corporate profits in GDP grows and if sustained indefinitely, this would mean that corporate profits eventually became larger than the economy.

What's more, the growth rates of the largest firms represented in the benchmark indices - will on average be slower than the growth rate of the corporate sector. Its much easier to double your sales when they're $50m than when they're $50bn. Overall, we should expect average market earnings to grow a bit less than GDP over the very long term and assess how fairly valued a market is on that basis (although small open economies such as Hong Kong and Singapore may be an exception, since some of the biggest firms will derive most of their profits from outside their local economy).

Growth is not a reason to invest in Asia

There's little doubt that Asia will grow significantly faster than the West over the few decades. But that will only reward us if we pay a fair price for those growth prospects.

This is more of a problem for investors who use funds especially trackers and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) than anyone else. Personally, as a stock picker, the promise of growth isn't my argument for investing in Asia. I can think of at least four better ones:

1)Diversification

Most investors have the vast majority of their assets invested in their home country. While it feels safe to invest in what you know best, the safety is an illusion. They're betting everything on a single economy and many Western economies have serious structural problems. They'll probably avoid disaster, but a UK-only investor will grow poorer relative to the rest of the world especially since Western currencies seem likely to suffer long-term devaluation against Asian ones.

2)Cheap value stocks

I don't believe any markets are efficient, but there's a sliding scale of inefficiency and emerging markets are likely to be even more inefficient than developed ones. That means there are plenty of overlooked companies for a stock picker to focus on. In emerging markets, even established solid companies often have little visibility and have no chance of making it on to the list of eligible stocks that big funds are allowed to buy. Lack of interest should mean they're better value.

3)Structural shifts

Far more interesting than fast growth is that fast-growing economies are usually undergoing profound structural shifts: rising consumption, urbanisation, infrastructure investment, better healthcare, a bigger role for financial services, more media and advertising, to name a few. You should aim to spot good plays on these themes when they're still cheap. Big themes often turn into bubbles dotcoms, biotech, railways, canals are just a few examples from history holding out the prospect of not just fair returns on fundamentally sound stocks, but the possibility of being able to sell out at inflated valuations when the mob mentality takes hold.

4)The rise of Asia and decline of the West

The broad macro trend of the next century will be rising wealth and power in Asia and relative decline in the West. That's not news. But what I don't think is so widely appreciated is the way in which money will flow out of Western markets and chase the growth story in Asia. Markets will become deeper, more liquid and more sought after. Small and medium-sized stocks that fund managers don't look at now will be on the shopping list in a decade or so. So we should profit from a re-rating of these markets. The MSCI Asia ex Japan has historically traded in a range of under one to just over three, but the next peak could be significantly higher.

To my mind, that's a lot of tailwinds to help the stock picker. But only a couple of them apply to indexing investors i.e. those who use ETFs or other low-cost trackers to follow the overall market rather than picking individual stocks. Certainly they get the benefit of diversification. Re-rating should also benefit them as well, although smaller stocks that won't typically be in indexes should benefit even more.

Pick your ETFs with care

However, straightforward indexing is not about picking obscure value stocks. And the point at which themes get their own ETF marks the point at which they are no longer a secret and quite a chunk of the value will already have disappeared.

This not a criticism of ETF investing. I write about ETFs frequently and will continue to suggest some in this email. I think they're far superior to investing in the majority of managed funds that are effectively trackers with higher fees. And the low-cost advantage of ETFs versus buying stocks directly shouldn't be ignored, although it is worth noting that firms like TD Waterhouse are now offering Hong Kong and Singapore stocks for flat fees of around £10-£15/trade less than we were paying for UK stocks a few years ago.

(On this subject, we're still going through the responses to the survey last week, but I noticed that many UK readers asked for suggestions on good low-cost brokers to buy foreign stocks. I'll write a detailed piece on this soon indeed, we're hoping to get a comparison table on the website but I'd suggest investigating TD Waterhouse, Saxobank and Interactive Brokers for execution only and Barclays, Killik & Co and Redmayne Bentley for advisory services with a wider range of markets.)

But index investors must be careful. A stock picker can find a fairly-priced stock in an expensive market. There are Japanese companies that have posted positive returns since 1989, such as Toyota (see below). But an index investor will only be rewarded if the entire market is reasonably priced.

The good news is that Asian markets in general still look decent value even after this enormous rebound (in contrast to the US). But after such a quick recovery, investors should certainly be asking whether some markets have got ahead of themselves. Next week, I'll take a look at where we stand in this rally and where I think the best value is now.

This article is from MoneyWeek Asia, a FREE weekly email of investment ideas and news every Monday from MoneyWeek magazine, covering the world's fastest-developing and most exciting region. Sign up to MoneyWeek Asia here

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn