Beware the hidden risks when investing in emerging markets

Emerging markets look cheap compared with developed countries, but earnings may be less trustworthy.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Developing countries look cheap compared with developed markets, but earnings may be less trustworthy.

Investing in emerging markets (EMs) has felt distinctly uncomfortable lately. At a time when developed markets are performing well, the MSCI Emerging Markets index is still down by around 6% in US dollar terms since the start of 2018. By contrast, the S&P 500 has gone on to set regular record highs and even the underperforming FTSE 100 is not far off its peak.

Value-orientated investors will comfort themselves that emerging markets look pretty cheap. The MSCI EM trades on a price/earnings ratio of around 14, compared with 22.5 for the US and 17 for Europe. You'd expect emerging markets to trade at lower valuations than developed ones because they carry greater political and economic risks. But a gap like that should compensate you for quite a lot of risks.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Emerging markets are also more biased towards cyclical sectors: the MSCI EM has around 25% in financials and 15% in energy and metals, compared with 13% and 7% respectively for the US. So purely in terms of the mix of earnings, there's good reason for emerging markets to trade a bit more cheaply. However, this can be easily taken into account.

The creative accounting challenge

The more difficult problem is whether those reported earnings are trustworthy. We all know that companies sometime manipulate earnings, either to make themselves look better or disguise outright fraud. So is this problem consistently worse in emerging markets? Some recent research by Rayliant Global Advisors, an Asia-focused investment manager, suggests that it is.

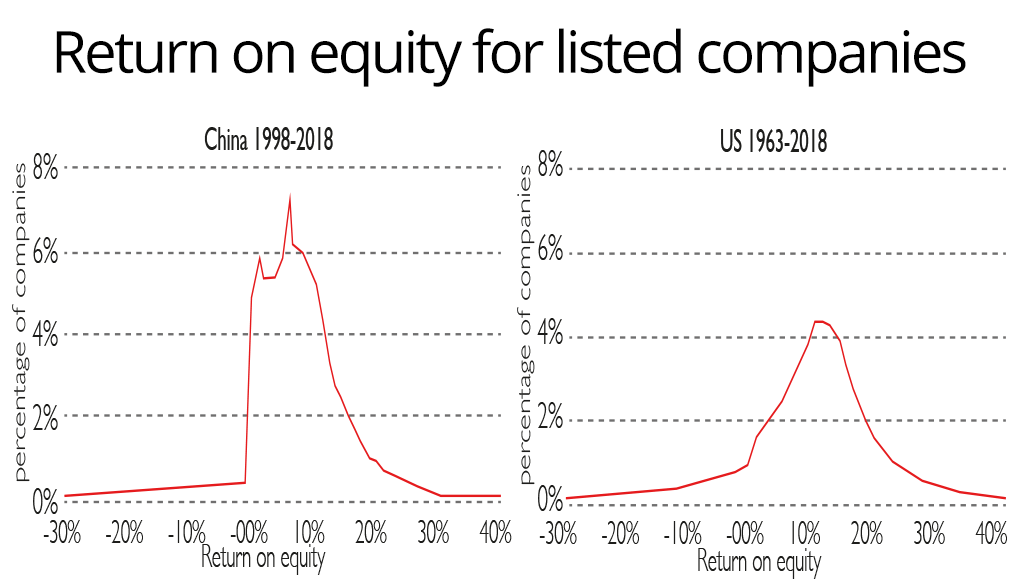

If we look at the distribution of companies' return on equity (ROE see below), we'd expect to see that a few companies report very negative ROE (ie, big losses) and very positive ROE (big profits), but most results to cluster around an average. This will vary between markets, but would probably be somewhere between 5% and 15%. The result should be a fairly smooth, symmetrical curve (ie, close to what statisticians call a bell curve or a normal distribution).

If you do this for a market like the US or UK, that's what you get, says Rayliant. Companies are a bit more likely to report earnings that are just above zero than you'd expect, but you have to look closely. But if you do the same for China or any of the other big emerging markets, you see a jump near zero. The unavoidable conclusion is that a substantial number of firms are reporting misleading results and may be making losses.

EMs are probably still quite a bit cheaper than developed markets and hence offer better long-term prospects. But dodgy accounting means they are unlikely to be as cheap as they look.

I wish I knew what return on equity was, but I'm too embarrassed to ask

Return on equity (ROE) is a useful measure of how good a company is at turning money that belongs to investors into profitable activity. It is calculated by dividing the company's post-tax profits (also known as net income) by the value of its shareholders' equity (which is the amount of money that would theoretically be available to pay to shareholders if all its assets were sold and its debts paid off). A more efficient company will typically have a higher ROE although sustainable ROEs vary between industries and sectors, so you should compare the firm to close peers to get an idea of how well it is performing.

Let's assume Company A has profits of £100m and equity of £500m. That gives it an ROE of 20% (£100m £500m). All else being equal, that means it is probably a better-quality organisation than Company B, which has profits of £200m and equity of £2bn an ROE of 10%. Equity investors are seeing their money work twice as hard in the first company as in the second, which bodes well for future returns, and for what the firm will earn from profits that it doesn't pay out as dividends.

A high, stable ROE can be a sign of a very good company. It is wise to calculate ROE over at least five years and preferably longer, as cyclical businesses can show a very high ROE over short periods while having low average returns over the long run.

ROE's weakness is that firms with lots of debt and little equity may show a higher ROE than less-leveraged rivals, even though they may not be better (they may well be riskier due to the extra debt). So you should also look at return on capital employed (ROCE), which takes all sources of financing into account. Let's assume that Company A also has debt of £500m meaning it makes a return of £100m on capital employed of £1bn, giving it an ROCE of 10%. Company B has no debt at all, meaning that its ROCE is also 10%. So Company A no longer looks superior.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement today (3 March). What can we expect in the speech?