Markets are getting over their burst of summer panic – but why?

Not so long ago, investors were despondent, diving headfirst into “safe haven” bonds. Now, however, markets have perked up. John Stepek explains what’s going on.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Just a quick reminder have you booked your ticket for the Wealth Summit yet? If not, get on it now it's happening in exactly a month from today.

We all suffer from "home bias" as investors.

In other words, we put too much of our money into our "home" markets, regardless of how important they are in global terms.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

We also suffer from a more subtle version of home bias. It's very hard to see past the fog of our own domestic dramas, to what's going on in the wider world even though the latter often matters a lot more for investment prospects.

So let's lift our heads from the murky gloom of Brexit for a minute, to see what's going on in the rest of the world.

Here's why markets are getting over their summer panic

Here's a quick reminder. A few short months ago back in August the world was plunging into despond. Government bond yields plumbed new depths in many countries, as investors dashed for "safe haven" assets.

A quick explainer. Bonds are IOUs when you buy a bond, you are effectively lending your money to someone. The bond yield is the interest rate that the borrower will pay you.

Bond yields fall as bond prices rise (because the yield is the interest payment expressed as a percentage of the price). So when bond yields are falling, it means that demand for bonds is high.

Why is high demand for government bonds indicative of a desire to invest in "safe" assets? Most developed-world government bonds are viewed as "safe" assets, because you'll almost certainly get your money back (ignoring the impact of inflation).

Developed-world governments don't typically go bust, because most of them can in extremis print their own currencies. (The eurozone is a special case, but we won't get into that side of things right now.)

So there you go. Bond yields were plunging, because investors were worried. Yet in recent weeks, we've been pulling back from the brink. Markets are rising again America's S&P 500 index perked back up to above 3,000 yesterday, for example. For all the political chaos, investors are less worried than they were in the summer.

What's going on? You might hear stuff about trade deals and Brexit deal hope, but I have a theory one that I've thrown your way before and it's not really got anything to do with either of those. Quite simply, it's all about Europe. Let me show you a chart, to prove the point.

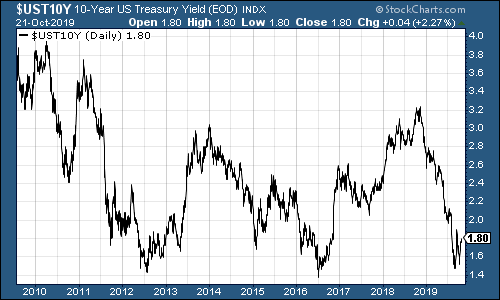

Below is the US ten-year yield over the last ten years or so (via StockCharts.com). You can see that there have been three spasms of panic that have sent bond yields to extraordinary lows.

What do those three spasms of panic have in common? Well, that slide lower in 2012 happened just before Mario Draghi said that he was going to do whatever it took to save the euro.

And you see that slide in mid-2016? That happened just as everyone had a minor heart attack following Britain's vote to leave the EU.

And you see that most recent plunge in the middle of this year? That was happening as Draghi's retirement approached and the European Central Bank appeared to be in two minds about loosening monetary policy, even as banking sector stocks were falling through a hole in the floor and the German economy was on the slide.

Europe is the bogeyman hanging over global markets

So what changed on each of those occasions? In 2012, the ECB made it clear it would underpin the eurozone by printing money as and when necessary. All through 2016, Draghi was fighting (and winning) the battle to do as much quantitative easing (QE) as he wanted. The post-Brexit vote spike marked the last gasp of fear on that particular front.

And most recently, we've seen Draghi leave his job as ECB head by passing Christine Lagarde a full-blown money-printing machine which is now on autopilot. Unless she is forced to switch it off by the northern European contingent (which is a much harder thing to do than deny her permission to switch it on), then the eurozone's sovereign debt and banking system is now underwritten in much the same way as those of the UK and the US are.

Why has the eurozone been the focus of all this deflationary fear? Put simply, because it's massive, and it's also the only developed-world region where investors are still worried that the banking system could collapse. That in turn could destroy the euro, and that in turn would be a deflationary blast along the lines of Lehman Brothers, although probably worse.

For a market that has been psychologically scarred by 2008, the fragility of the eurozone is the scariest thing in the world.

Now, it's not just the eurozone. The fact that the Federal Reserve is making efforts to tackle the problems in the repo market, with the aim of avoiding inadvertently tightening monetary policy, has helped. That will help the US dollar to weaken, which in turn is great news for everyone else.

But make no mistake, the prime deflation bogeyman in the investment universe right now is Europe.

What I wonder is this: what happens when investors finally start to believe that the eurozone problem is fixed?

After the sense of relief, how long will it be before they start worrying about inflation again?

Hopefully we don't have that much longer to find out. This is why I'm not in any great rush to get out of the market in general (stocks would like a more inflationary mindset at first). And it's also why I would remind everyone to have a wee bit of gold in their portfolios.

Oh, and book your ticket for the Wealth Summit! We'll be talking about all of this and more don't miss it.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?