Great frauds in history: Stanford’s great bank-bond heist

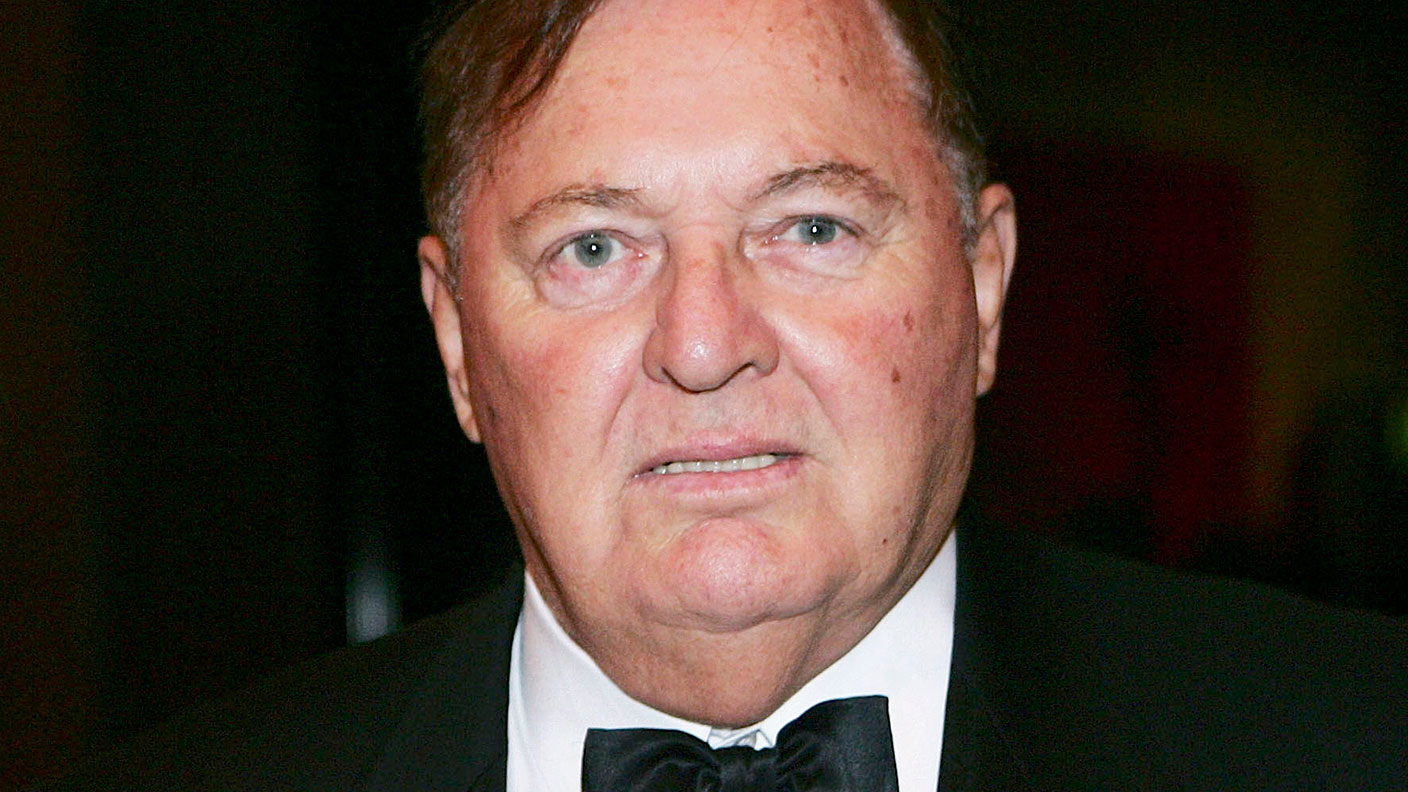

Matthew Partridge looks the fraud perpetrated by Robert Allen Stanford, which netted him $7bn from certificates of deposit.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Robert Allen Stanford was born in Texas in 1950 and made a living running a gym before that failed and he turned to speculating in real estate in Houston in the 1980s. He made his fortune, then moved to the Caribbean island of Montserrat, setting up the Guardian International Bank, then moving it to the nearby island of Antigua and renaming it Stanford International Bank (SIB) to avoid a regulatory crackdown. He also set up a wealth-management firm, which encouraged clients to invest their money in certificates of deposits (CDs, redeemable bonds used by banks) issued by Stanford International Bank. These offered a higher interest rate than CDs offered by US banks, but were supposedly backed by insured assets.

How did the scheme work?

Instead of being invested in a wide range of assets, as promised, much of the money received by SIB was loaned out to Stanford and his companies and property schemes, which consistently lost money. As a result, SIB was forced to keep issuing new CDs in order to repay its existing creditors (in other words, it was much like a Ponzi scheme). To disguise the bank's true financial position, Stanford misreported the bank's assets and even forged an insurance certificate.

What happened next?

Thanks to aggressive marketing, Stanford managed to sell $7.2bn worth of CDs. Stanford's fraud imploded when the financial crisis led investors to seek to redeem their bonds. The crisis made it impossible for Stanford to sell any of his private firms to raise money. In a final roll of the dice he promised to inject $741m into SIB, but much of this came in the form of land originally bought for $64m a few months earlier. By February 2009 the FBI had raided Stanford's offices, and he was sentenced to 110 years in prison in 2012.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Lessons for investors

American CDs are normally protected by depositor insurance schemes, but Antigua doesn't offer similar protection. As of October 2017, receivers had managed to get back only $350m of $7bn for CD holders, roughly 5%. The scandal shows it is a bad idea to invest money in offshore banks where protection for investors is minimal and regulation inadequate. Indeed, for a time, Stanford was the chairman of Antigua's financial regulator.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?Whether you’re an ISA investor seeking reliable returns, looking to add a bit more risk to your portfolio or are new to investing, MoneyWeek asked the experts for funds and investment trusts you could consider in 2026

-

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continue

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continueIt was another difficult year for fund inflows but there are signs that investors are returning to the financial markets

-

Christopher Columbus Wilson: the spiv who cashed in on new-fangled radios

Profiles Christopher Columbus Wilson gave radios away to drum up business in his United Wireless Telegraph Company. The company went bankrupt and Wilson was convicted of fraud.

-

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoax

Great frauds in history: Philip Arnold’s big diamond hoaxProfiles Philip Arnold and his cousin John Slack lured investors into their mining company by claiming to have discovered large deposit of diamonds. There were no diamonds.

-

Great frauds in history: John MacGregor’s dodgy loans

Profiles When the Royal British Bank fell on hard times, founder John MacGregor started falsifying the accounts and paying dividends out of capital. The bank finally collapsed with liabilities of £539,131

-

Great frauds in history: the Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company's early Ponzi scheme

Profiles The Independent West Middlesex Fire and Life Assurance Company (IWM) offered annuities and life insurance policies at rates that proved too good to be true – thousands of policyholders who had handed over large sums were left with nothing.

-

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empire

Great frauds in history: Alan Bond’s debt-fuelled empireProfiles Alan Bond built an empire that encompassed brewing, mining, television on unsustainable amounts of debt, which led to his downfall and imprisonment.

-

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt binge

Great frauds in history: Martin Grass’s debt bingeProfiles AS CEO of pharmacy chain Rite Aid. Martin Grass borrowed heavily to fund a string of acquisitions, then cooked the books to manage the debt, inflating profits by $1.6bn.

-

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scam

Great frauds in history: Tino De Angelis’ salad-oil scamProfiles Anthony “Tino” De Angelis decided to corner the market in soybean oil and borrowed large amounts of money secured against the salad oil in his company’s storage tanks. Salad oil that turned out to be water.

-

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debts

Great frauds in history: Gerard Lee Bevan’s dangerous debtsProfiles Gerard Lee Bevan bankrupted a stockbroker and an insurer, wiping out shareholders and partners alike.