Investing in longer lives will lift your portfolio

People are living longer than ever before – and the old are starting to behave as if they are merely middle-aged. Therein lies opportunity, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Earlier this week The Economist ran a leader headlined "How Japan can cope with the 100-year-life society". It was full of interesting titbits (more than half of Japanese babies can expect to live to 100, for example) and helpful advice: Japan must raise its retirement age. But there was something about it that reminded me of all the articles about the Japanese financial crisis written by Western journalists in the 1990s.

They, too, were full of interesting facts (how much the land the Imperial Palace sits on was worth in 1988 compared with 1995, for instance) and advice (boost productivity, create inflation, and so on). Our press was so busy patronising the world's third-biggest economy that it failed to realise that where Japan went, we would follow. Their problems are also our problems.

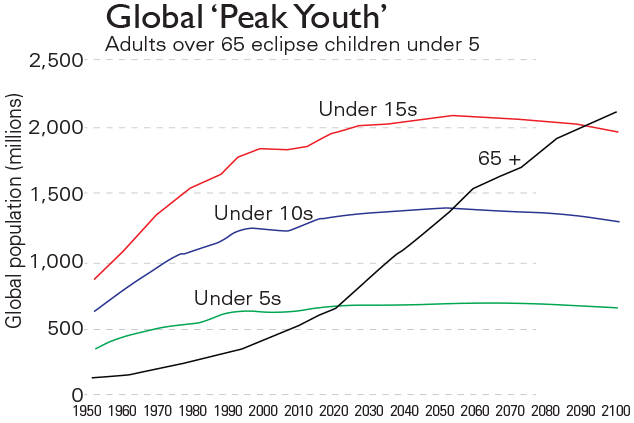

We can't quite say that 50% of UK babies will live to 100 but depending on which numbers you look at, a good one in three or four will. This dynamic is global. In the UK we have gained an extra 30-odd years of life since the introduction of the state pension. Add that to the falling fertility rates around the world (the global rate is down from 4.7 in 1950 to 2.4 last year), and Axa Investment Managers point out that "2018 will be the first time in history that the global number of adults aged 65-plus will outnumber children under five" (see chart below).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Step-change in longevity

This is all happening very fast indeed. Professor Laura L Carstensen, founding director of the Stanford Centre on Longevity, makes the point dramatically. The first four million-odd years of human history produced an 11-year rise in life expectancy (from 20 to 31). The 115 years from 1900 to 2015 produced a 41-year increase. And it isn't anywhere near over yet: the 65-plus cohort is going to grow more than four times as fast as the broader population from 2020-2030, while the over-80s cohort "will more than triple in the next 35 years". There is also the chance that things will move even faster that there will be a "step change".

Much of the conversation at the inaugural Longevity Forum at the Wellcome Collection a few weeks ago was about the newish field of senolytics, which might have found ways (in mice at least) of actually reversing ageing. My favourite statistic? A 20-year-old today has a better chance of having a living grandmother than a 20-year-old in 1900 had of having a living mother. You can think of all this as a very bad thing indeed. Health bills will soar. Pension systems will collapse. The countryside will empty and of course the global economy will collapse as there are no longer enough young people knocking around to staff the factories let along provide care for the elderly.

Old people aren't acting their age

But you could also think of it something rather marvellous. The old of today are not remotely like the old of the past, a trend that will accelerate as we find ways to biologically alter ourselves and deal with long-term chronic diseases such as cancer immunotherapy may be the answer here and diabetes: we already have evidence that intense low-carb dieting can reverse the obesity-related Type 2. Even now older people are in remarkably good shape. It's beginning to look as if ageing is "malleable", says Carstensen. Some 50% of 85-year-olds say they can work. The Economist quotes Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as saying that "today's elderly Japanese walk as fast as those ten years younger once did".

The incidence of dementia in the US is actually falling, not rising. And, as research from Enders Analysis notes, the over-50s the "new old" no longer act their age. They are apparently "down-ageing: acting younger and spending much more than they ever did before".

Middle age is getting longer

It is not old age, then, that is getting longer. It is middle age. This has obvious social implications. We need to encourage systems where people can dip in and out of education over a lifetime and are better able to change careers, and hence find ways to let even those in their 80s be productive, valued members of society. This sounds simple but in fact adds up to a complete reshaping of the world as we know it. Until the 1950s, all countries had pyramid-shaped populations lots of young people at the bottom, a couple of oldies at the top. These days, those pyramids are fast turning into rectangles and eventually will be narrow upside down pyramids. Look at Japan's population pyramid and you will see that it is already top-heavy.

Companies and governments haven't adapted

This is not being recognised by our institutions. Look around you. Corporations haven't adjusted to fast-rising lifespans. Try changing career at 55 or even sticking with your original one past 65. There is also a tendency everywhere to pay older workers more than younger ones, regardless of skill level. This isn't easy to change but it isn't helpful, either. Japan is doing a little better on this than us in some areas. It has the highest share of over-65s in the workforce in the G7, and more women in the workforce as a percentage of the population than even the US. As for education, if you are going to live to 95, why stop learning at 16, 18 or even 21 and never restart? New skills aren't very often going to be a waste of time during a 60-year working life. And finance? The industry will still try to "lifestyle" your portfolio into bonds at 50 regardless of the fact that you have barely hit middle age. The property market is also utterly hopeless in this regard. As it becomes possible for four generations of one family to be alive at the same time we are still segregating them by building miserable rabbit-hutch homes for the young and even more miserable retirement flats for the old. Why aren't we building long-term housing with sections for younger families, their older relations and a carer too?

The state hasn't adjusted either. Look at the way our government hands out our money willy-nilly to those who quite obviously don't need it. At the Longevity Forum, Lord Adair Turner gleefully waved his free travel pass (available to the over-60s in London). If he can perform at high-level conferences, he does not need taxpayer support to take the Tube.

How to profit from longevity

From an investor's point of view, there are several things to think about here. If you are stock-picking for the long term, it might make sense to buy into companies that get this. Look at the marketing strategies of most companies. Cruise ship, slipper and stair-lift products aside, you will see they are marketing to the wrong age group. Advertisers are fixated on the young. Yet the median pound in the UK is spent by a household headed by a 47-year-old. And globally things looks much the same, says Axa: the 60-plus cohort is "forecast to account for 55% of global consumption growth in North America, Western Europe and north-east Asia from 2015 to 2030". They are spending on home improvements (so they don't have to move), on travel, and on beauty (Europeans over 60 spend twice as much on beauty as under-25s). They are also huge participators in the digital economy (transacting almost as often as millennials).

Right now the 50-plus market is a target of only around 10% of the marketing dollars in the US, says Axa, while advertisers spend around five times as much trying to reach (broke) millennials than on all other age groups combined. That's probably a big mistake. Secondly, the idea of longevity is extremely attractive to investors. Any product that turns out to extend life is going to fly off the shelves. It's also being talked about more and more as a sector in its own right, and the amount of cash pouring in is accelerating fast. That, reckons longevity investor Jim Mellon, means it may soon generate its very own speculative mania.

It is early days for the investability of this sector. The Global X Longevity Thematic ETF (Nasdaq: LNGR) which should be the easiest way to access it isn't as easy as it should be: you can't buy it on most UK platforms. You could instead look at the iShares Ageing Population UCITS ETF (LSE: AGES) which tracks shares in companies providing services or goods to the world's ageing population. It isn't quite the same thing but you can at least buy it easily. Otherwise, Axa has jumped on the bandwagon by rejigging a health fund to create the Axa WF Framlington Longevity Economy fund (available via some wealth managers), and in the US there is a new and small fund called The Longevity Fund that makes investments in firms (seven so far) that "aim to extend the period of healthy human life" (again call your wealth manager). Otherwise there are several big funds that have relevant stocks in their portfolios. MoneyWeek readers who hold the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust will have exposure to the longevity-related investments in its portfolio. Investment trust Syncona is another possibility.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?

Plan 2 student loans: a tax on aspiration?The Plan 2 student loan system is not only unfair, but introduces perverse incentives that act as a brake on growth and productivity. Change is overdue, says Simon Wilson